Keeping time with the algorhythm

Giulia Reche-Danese explores the potential and risk involved in placing one’s musical faith in the all-knowing algorithm

I really don’t think I’ve ever witnessed a miracle, but there have been a few times that felt rather close. For example, when I’ve been lucky enough to call out in disbelief “Wait, there’s no way you know that band?!”

There’s an incomparable thrill to someone you just met unexpectedly knowing an extremely specific, forgotten band with just a few hundred monthly listeners. What makes these interactions so special is of course their unlikeliness. The odds of them taking place are so low that when they do, they almost feel as supernatural as a miracle. It even feels like a miracle in itself that you came across the band.

“It even feels like a miracle in itself that you came across the band”

So, how did you? In my case, I realized soon enough that the answer was tragically anticlimactic: in practically all cases, I’d simply stumbled across it on Spotify as it got automatically recommended to me.

As most of my musical discoveries come from these ‘random’ recommendations, it’s gutting to think that the songs I’ve grown to love and form deep connections with came from a perfectly calculated system. Every nuance of my listening habits had been analyzed to find matches that the algorithm was almost certain would correspond to my taste.

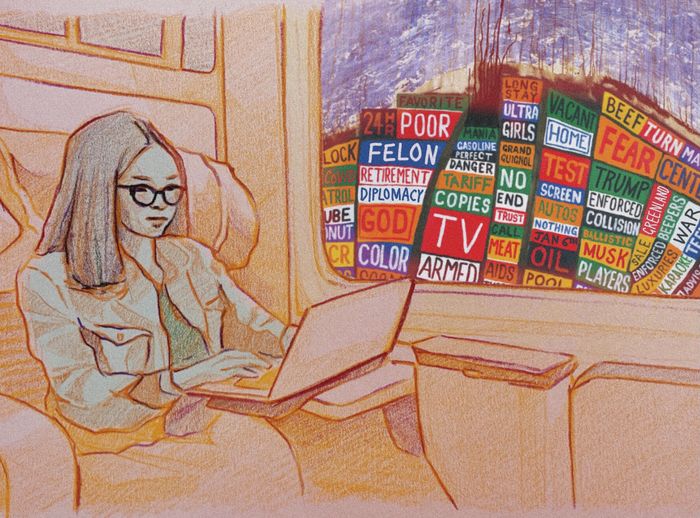

A rather dystopic scenario: unexpectedness, spontaneity, and diversity get completely factored out, and taste is reduced to a very optimized prediction. The beauty and whimsy from defying the odds is far from being enhanced, it’s taken away.

The odds are not being defied in the slightest: stumbling across that band was a perfectly calculated outcome, the exact opposite of unlikely. Yes, perhaps it was unlikely that two people with such similar music taste happen to cross paths, but if all it took was an algorithm, it soon becomes a much less exciting coincidence. What I thought was an alignment of fate turned out to be the result of an algorithm’s calculations. Not so dreamy anymore.

And the worries go beyond just robbing these ‘chance’ encounters of their poetic beauty. By making our relationship to art an infallible matchmaking process, we are taking away from the growth and evolution that stem from trial and error. If we lose the unpredictable, how can we become complex, multifaceted – ultimately, interesting – individuals? So much of who we are, were and will become can be understood through the music that shapes us: it’s rather tragic for unpredictability, unexpectedness and spontaneity to be systematically ruled out, replaced by standardized answers given by a machine.

Put in this way, the Spotify algorithm appears truly terrifyingly alienating, and I’m urged to immediately give it up and desperately run across charity shops hunting for vinyls, cds or whatever fate will put in my way. But this doesn’t feel like the full story.

The more I think about it, the more I see a certain poetic beauty in the fact that we can just get handed songs by an algorithm. In the impersonality of being assigned something exclusively meant for each of us by a machine, there’s something almost prophetic. Admittedly, a perfectly curated calculation is the very opposite of fate. But there is something undeniably similar in the way in which we perceive it.

We stumble across these songs knowing only vaguely why they get to our ears. In that sense, it’s as if we were predestined to find them, as if they were gifts sent from above.

Besides, the idea of infallibly matching what goes together appeals to the beauty of a perfect cosmos. Perhaps tailoring our world vision to the Stoics’ is a bit extreme, but I can’t help but love the thought of a harmonious correspondence between each artwork and those who appreciate it. If some works of art are meant to find each of us, they fascinatingly have something for us resting inside, and who knows how that got there! It reminds me of the Androgyne myth in Plato’s Symposium, where Aristophanes jokingly claims that we are meant to find the people that used to constitute our literal other halves in a very distant past life. But instead of being separated from our soulmate, it’s as if we’ve been separated from the art that initially constituted us. Living is then realizing who we are by piecing together the art that used to be part of us.

“If some works of art are meant to find each of us, they fascinatingly have something for us resting inside, and who knows how that got there!”

So, I choose to see some beauty in the algorithm. In its attempt to perfectly understand what songs fit us most, it highlights how crucial music is to who we are. Of course, I would hope our appreciation of art is deeper and more complex than what can be clocked by an algorithm.

We shouldn’t let its recommendations dictate our taste, but take them with a grain of salt. Taking each song as an opportunity to exercise critical thinking as much as possible, challenging even what we deem familiar, allows us to refine our taste more and more – get a little closer to understanding who we are. Yes, the algorithm might be like an oracle, but the difference is we’re not Oedipus. Its prophecy is merely a starting point, the interesting part is figuring out the rest of the story.

News / Colleges charge different rents for the same Castle Street accommodation2 March 2026

News / Colleges charge different rents for the same Castle Street accommodation2 March 2026 News / King’s hosts open iftar for Ramadan3 March 2026

News / King’s hosts open iftar for Ramadan3 March 2026 Theatre / Lunatics and leisure centres 4 March 2026

Theatre / Lunatics and leisure centres 4 March 2026 News / Angela Merkel among Cambridge honorary degree nominees27 February 2026

News / Angela Merkel among Cambridge honorary degree nominees27 February 2026 News / News in Brief: waterworks, wine woes, and workplace wins 1 March 2026

News / News in Brief: waterworks, wine woes, and workplace wins 1 March 2026