Picket lines and strikes are what real politics looks like

The ongoing staff strikes at Cambridge have led Alice Hawkins to reflect on the realities of political engagement

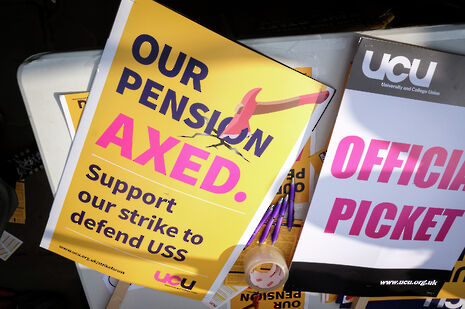

Sidgwick Site at 9am on a Monday morning was never made to be a thing of beauty. But on this particular morning, it looks a little different. People are standing in groups gathered around the entrances. They rub their hands together against the cold, have a laugh, pour another cup of tea. Someone’s brought their dog; he sits there, patient and comfortable, blissfully oblivious. In a sudden cacophonic burst, a car roars by on West Road, horns blazing and driver leaning out of the window to wave and yell a message of support. The gathered crowd responds, cheering, waving their yellow signs back in recognition. He disappears around the corner – the gentle chatter resumes.

The next visitor is received with a little less receptiveness. He sits on his bicycle, looking pained, eyes fixed on the faculty building that taunts him in the none-too-distant future. He struggles to make eye contact with members of the group gathered before him. His eyes flick up and down to the asphalt beneath him. The equivocation is written on his face. He doesn’t know what to do; what is right to do – what is right for him to do. He’s thinking, but this one has no easy answer. He’s paused.

“Please don’t cross the picket lines.”

With a barely perceptible shake of his head, the student turns and rides away.

Exchanges like this continue; their outcomes vary. Others elect to ride on, tearing holes through the lines before them. Still others apologise profusely, asking for understanding, manoeuvring awkwardly through the crowd. One girl barges through, music blaring from her headphones, eyes fixed on the ground, flinching away as she’s tapped on the shoulder by one of the picketers. The scene continues to unfold throughout the day. It is a scene that will unfold again tomorrow. And played out against the rather pertinent backdrop of the Allison Richard building (the Department of Politics and International Studies at the University of Cambridge) it’s a scene that finally – finally – gives an insight into what real politics looks like, more so than any book contained within the libraries behind the ARB’s closed doors.

“This is real politics. It’s personal. It’s a lived experience that you are a part of and implicated in, whether you had asked to be or not”

Sidgwick Site at 9am on a Monday morning: this is what real politics looks like. It’s a steadfast, ongoing display of resistance. It’s the acting upon principles that can’t be reconciled with a simple continuation of day to day existence. It’s uncomfortable, it’s challenging. It’s the navigating of boundaries; physical, ideological, and ethical. It is sacrifice. And it is a deeply personal process. Your thoughts, feelings and actions aren’t mandated to you by another. There’s no one there to tell you what is right and what is wrong. You are your own political agent. Perhaps you feel distressed because your routine has been disrupted. Perhaps you feel guilty, or perhaps you feel compelled to take action. Perhaps you don’t.

It’s up to you.

This is real politics. It’s personal. It’s a lived experience that you are a part of and implicated in, whether you had asked to be or not. You can see it affect your peers, friends, teachers, and different members of your community in different ways, to different degrees. Its implications are multiple, various, and fundamentally shaped by the actions that you choose to undertake.

This is real politics. It’s not grand orations pandered to a national audience, nor the cleverly manipulated rhetoric traded between competing elites in their struggles for power. It’s not landslide election victories, nor declarations of war. And it’s definitely not the intellectualised arguments bound within the covers of my politics books.

I am a politics student and I have read a lot of these politics books. I could tell you all about the significance of Nietzsche’s slave revolt of morality. I could wax lyrical about the artificiality of justice as a virtue, according to Hume. I could run circles around you with my crudely understood Foucauldian discourse – it would make for a great performance piece. But none of them could have shown me what I have seen unfolding across our university over the last few days. None of them could have taught me what I have learnt from these events.

“There exists in this institution a bizarre cognitive dissonance between people’s willingness to engage in political theory and their willingness to engage in political reality”

This is a letter to myself. It is a letter about self-reflection. The impacts of these strikes are extraordinary because they are intimate. They are forcing engagement with the real political issues that have a direct impact upon us – right now, standing outside our lecture halls, and for a long time into the future. They are forcing a new level of cognizance of the institutional power structures within which we exist, yet so often fail to recognise. They are forcing a recognition of the political agency which we all possess. And from my experience, the best kind of political agents that we can strive to be – the best kind of people – are those who are thoughtful. Those who can reflect on their own context, experiences, and values to challenge their own assumptions about the way the world works, and evaluate their role within it.

And that is why I could not cross the picket line at 9am on Monday morning, and will not cross the picket line an any time while strikes continue. Because with what kind of audacity could I stay cooped up in King’s College library, writing up grandiose claims about the political efficacy of mass organisation in the Middle East, whilst my eyes remained closed to the political organisation unfolding outside my very own window? With what kind of horrible irony could I continue to sit there, making my characteristically overconfident assertions of authority on the true meaning of Rousseau’s discourse on the origin of inequality in society, all the while pretending I couldn’t hear the chants of protest carried over from the front lawn from Senate House? Who do I think I am to criticise the failure of development programs to engage with the local politics and lived experiences of the societies in which they intervene, if I am not even willing to do that myself?

I’m a politics student because I care about politics. And unfortunately for even the most purportedly apolitical among us, politics impacts everyone. That’s why it matters. That’s what I told my interviewers. That’s why I write my essays. That’s why I’m here – and I’m sure there are many who feel the same way. Yet, from my experience, there exists in this institution a bizarre cognitive dissonance between people’s willingness to engage in political theory and their willingness to engage in political reality. I know firsthand which place is the more comfortable place to be. I know the temptation that exists to retreat from the latter into the safe confines of intellectualised debate and armchair philosophising in the former. But if I’m not prepared to at least attempt to overcome this, I’m really going to have to start asking myself what kind of student of politics I think I am.

Isn’t it great I am able to deconstruct for you the tragic incoherence of Weber’s ethics of conviction and responsibility – and the “dirty reality” that “politics always chafes against the clean, straight lines of conduct” we try to follow (thanks, Runciman). But what use are my politics of good intentions if they merely betray a superficial lack of concern for the meaning of human action?

I call myself a politics student. What do I think I’m doing, trying to learn from books?

News / Reform candidate retracts claim of being Cambridge alum 26 January 2026

News / Reform candidate retracts claim of being Cambridge alum 26 January 2026 News / Report suggests Cambridge the hardest place to get a first in the country23 January 2026

News / Report suggests Cambridge the hardest place to get a first in the country23 January 2026 Interviews / Lord Leggatt on becoming a Supreme Court Justice21 January 2026

Interviews / Lord Leggatt on becoming a Supreme Court Justice21 January 2026 Comment / How Cambridge Made Me Lose My Faith26 January 2026

Comment / How Cambridge Made Me Lose My Faith26 January 2026 News / Cambridge psychologist to co-lead study on the impact of social media on adolescent mental health26 January 2026

News / Cambridge psychologist to co-lead study on the impact of social media on adolescent mental health26 January 2026