Grief in the time of Coronavirus

One year after the loss of her dad, Phoebe Page reflects on her experience of grief during the pandemic.

Strictly’s back on telly. This event usually would have passed me by – it’s hardly enshrined in the cultural calendar of your average 22-year-old – but this year it did not. Not so much a pastime as a literal marker of passing time, the first thing to remind me what this time of year means.

My Dad died one year ago this week, and sequins and sparkles and outrageously orange celebs played no small part in getting me through those first grief-stricken weeks, as nights drew in and social invites dried up. I’d never seriously watched the show before last October, when a wise nurse initiated me with the words, “it’s bubble-gum, but it’s what you need right now.” She was not wrong – it was a tonic and an escape, and Craig knows it is exactly what the British population need this winter. So as twelve new couples take to the glitzy dancefloor, it has given me cause to reflect on what exactly “one year on” means for the bereaved.

"Everything after those first devastating words was merely background noise, pitter patter on windows long after the storm had come hurtling through."

Losing my Dad was my first real experience of loss and while, granted, “no two experiences of grief are the same”, it soon became clear 2020 was going to be a particularly unique year for grieving. My Dad did not die from coronavirus, but from an advanced glioblastoma four weeks before the first virus case was reported. People talk about the death of normality, the havoc wreaked by the pandemic on all our lives, but for me normal was a foreign concept from the moment we received the news. Everything after those first devastating words was merely background noise, pitter patter on windows long after the storm had come hurtling through.

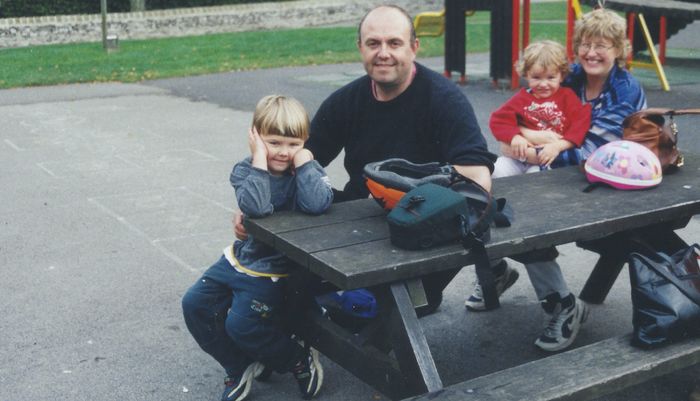

Everything happened very quickly; one minute Dad was running marathons and drinking me under the table three nights a week, the next he was in a coma in ICU having undergone emergency surgery to save his life. We didn’t know how long he had but we knew it was terminal – the doctors told us it could be days, weeks or months. Michaelmas term was fast approaching and a flight marking the start of my Year Abroad was booked, but there was no doubt in my mind about whether to intermit. However little time we had left to spend with him, I would not be getting on that plane.

Time has a peculiar way of playing out on the showreel of our memory. Sights, smells, overheard snippets of conversation from that first week are just as strong in my mind as the image of Dad’s beautiful smile. Then the week of his death: nothing. I was carried along on a wave of exhaustion and burnt-out adrenaline, my brain no longer working in overdrive to catalogue every microscopic detail for later processing. The early days of grief have merged in much the same way as later weeks of lockdown. Novelty soon wears off: people stop bringing you flowers and sourdough stops being interesting. Now, realising that a whole twelve months have passed since Dad’s death, I wonder if time would have gone faster or slower without a global pandemic to bridge the gap between my grief and the world’s.

Experiences of ICU are never pleasant, but in many ways we were lucky. We could visit my Dad all throughout his illness, hold his hand, play music as he slept. There were no plastic screens or whispered video-call goodbyes. Even when the doctors told us they were pulling the plug, the worst news for any loved one to hear, we were at least granted the luxury of being in the same room. The experience pales in comparison to the unimaginable trauma of patients’ families just months later.

"It became harder to fill the space his absence had left"

The pandemic, however, made itself felt in other ways. I have a tiny family, and in those first weeks our need for connection and external support was met by the incredible friends who gathered round us. Then in March I went into lockdown with my two closest relatives, still reeling from our family’s sudden loss, and we entered an intense, emotionally claustrophobic period of enforced reflection. The house became a melting pot of pent-up frustrations, pain, guilt – “why didn’t we catch it sooner?”, “would an earlier diagnosis have changed anything?” As a series of firsts crept up on us – first birthdays (our own and then Dad’s), the first wedding anniversary – it became harder to fill the space his absence had left. Plans to visit his favourite places, raise a toast among friends, scatter his ashes somewhere meaningful; all were put on hold again and again.

Now, of course, we are coming up to the real “first”. A friend recently wrote to me, commenting, “for some reason there is a poignance to the first anniversary of a death, even though 365 days is a pretty arbitrary number.” This is true, but then so is the number chosen for the rule of 6. An anniversary should be a celebration, and I know if my Dad were here and the pandemic were not (two parallel universe scenarios I frequently dream about) he would be first at the bar, getting orders in thick and fast so we could all raise a glass to his truly fantastic life.

“For some reason there is a poignance to the first anniversary of a death, even though 365 days is a pretty arbitrary number.”

Of course, people have found creative ways to cope with poignant moments during the pandemic, as I’m sure we will this Sunday. But as Dr Phyllis Kosminksy points out, creativity takes energy and energy is something that is often in short supply for people who are grieving. Which is why I couldn’t be happier to see the stars of Strictly Come Dancing grace our screens once more for another series of dazzling, daft, pandemic-defying escapism. There are still days when I do not feel a perfect 10, but good friends, good laughs and good telly go a long way to making life feel that little bit more normal again.

News / Right-wing billionaire Peter Thiel gives ‘antichrist’ lecture in Cambridge6 February 2026

News / Right-wing billionaire Peter Thiel gives ‘antichrist’ lecture in Cambridge6 February 2026 News / Cambridge students uncover possible execution pit9 February 2026

News / Cambridge students uncover possible execution pit9 February 2026 News / Epstein contacted Cambridge academics about research funding6 February 2026

News / Epstein contacted Cambridge academics about research funding6 February 2026 News / Man pleads guility to arson at Catz8 February 2026

News / Man pleads guility to arson at Catz8 February 2026 News / John’s duped into £10m overspend6 February 2026

News / John’s duped into £10m overspend6 February 2026