On Loss and Finding Laughter

Emily Claytor reflects on the complex emotions which follow the loss of a loved one

On Boxing Day 2019, my dad died suddenly from a heart complication. It was entirely unexpected and an uncharted form of pain. The following period felt like entering into a parallel universe: I intermitted, deciding that a year out would be preferable to launching myself into finals, and adapted to living back at home. Here I began the strangest year of my life, completely unaware of how meaningless that phrase would become in reference to 2020.

Time became divided into distinct zones of before and after; those early days in the latter are mostly an absent blur. There is one moment that stayed with me, however: the first time I laughed after Dad died. It was neither a deliberate milestone nor in response to something particularly funny. It had been a day or so and I was getting out of the car at home when a little boy walked past, doing a weird walk. I can’t even remember why, but it provoked a little laugh, followed by an uncomfortable tightening in my chest as I suddenly realised how alien this felt. It was ridiculous, but I felt guilty for experiencing something besides the obvious, painful sadness.

“I discovered that sadness and joy were not mutually exclusive”

After the death of someone close, it can feel like there is an expectation that life will become a constant meditation on serious things. I found myself becoming a careful editor of my own behaviour around anyone outside of my immediate family; making sure to display just the right level of sadness so as to not make people uncomfortable, but also not to cause them to think I was incapable of feeling. Truthfully, this feeling couldn’t be pinned down to a singular emotion, and it was easier to mask my inability to articulate how I felt by presenting myself in this way: with the “right” amount of grief. Back at home with my family, I was able to experience the reality of this odd mix with far more ease. The lack of pretence in our shared experience meant I could find comfort in laughter again. I discovered that sadness and joy were not mutually exclusive and that, although our lives had been damaged, their textures and emotions could remain the same. It was when we laughed that I knew we were not alone, despite our loss.

I also found a comforting outlet for laughter in television. In that first month, this took the form of rewatching Gilmore Girls for the fifth time. The cosy familiarity was perfect for zoning out from emotion entirely, switching off my brain and sending it to a liminal space in between me and my computer screen. During the following months, I moved through a catalogue of period dramas, sitcoms, and teen melodramas. The programme I valued most, however, was HBO’s early 2000s series Six Feet Under. Perhaps simultaneously the worst and the best thing I could have chosen to watch in my situation, this dark comedy follows the lives of a family of funeral directors after their father dies suddenly on Christmas Eve. It was, you could say, ‘on the nose’.

Grief is a ubiquitous theme in all media, but Six Feet Under navigated it in a way that felt the most powerful of anything I have ever read or watched. It is funny without being insincere. In one particularly amusing episode Nate, the eldest brother, arrives at the dinner table having accidentally taken ecstasy, in a sequence that perfectly showcases their endearingly dysfunctional family dynamic. Such moments exist as absurd relief from the ever-present backdrop of the funeral home, but they also humanise the characters, in turn heightening the profound effect as the show never deviates from its central themes of death, our fear of it, and its meaning. The same show performed as a straight drama would not only be deathly boring but would feel oddly superficial, because real humanity is not a coherent chain of complementary emotions but rather a nonsensical mix, from which humour is indispensable. Watching Six Feet Under articulated to me how, even with all its sincerity, life is not so simple that it can unfold without comedy.

“I think he would have agreed that grief, like most parts of life, can be funny”

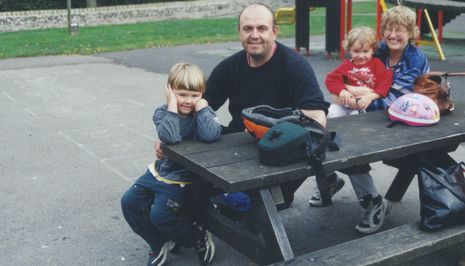

My dad was one of the kindest, most gentle people I have ever known. He was also one of the funniest. He and my mum watched Six Feet Under when it originally aired so it makes me sad that I’ll never get to talk to him about it. But I think he would have agreed that grief, like most parts of life, can be funny. It is absurd and unpredictable and to think that you can know what your response to it might be is naive. In allowing myself to spin this messy web of emotions that come with grief, each string gained clarity until I was living in neither a tragedy nor a comedy; I was simply human.

News / Colleges charge different rents for the same Castle Street accommodation2 March 2026

News / Colleges charge different rents for the same Castle Street accommodation2 March 2026 News / News in Brief: waterworks, wine woes, and workplace wins 1 March 2026

News / News in Brief: waterworks, wine woes, and workplace wins 1 March 2026 News / Climate activists protest for ‘ethical careers policy’1 March 2026

News / Climate activists protest for ‘ethical careers policy’1 March 2026 News / Angela Merkel among Cambridge honorary degree nominees27 February 2026

News / Angela Merkel among Cambridge honorary degree nominees27 February 2026 News / Private school teacher who lied about Cambridge degree barred from teaching27 February 2026

News / Private school teacher who lied about Cambridge degree barred from teaching27 February 2026