How fungi redefine the individual

Asha Torczon asks whether symbiotic relationships should make us reconsider our idea of identity

Human societies are built upon the concept of the individual, a single autonomous organism with interests, opinions, and the capacity for action. This view is superficially supported by what we see around us - I assume ‘I’ am the person I see in the mirror, and that the people around me have their own separate, internal perception of the world. However, diving into the strange interactions of the fungal world can prompt us to question where we draw the lines between organisms, including those as familiar as ourselves.

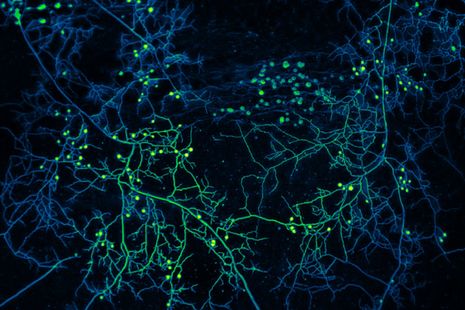

Fungi have been neglected in much of biology as they evade human observation, living mostly underground and in decaying matter. Mushrooms, the archetypical fungus, are the most superficial of fungal features, analogous to the fruit produced by a tree. The real body of a fungus is its hyphae: thin filaments that explore the surrounding environment, secrete digestive enzymes, facilitate nutrient absorption and exchange, and interact to form a complex network known as mycelium. These complex systems lack a central organiser, breaking rules that challenge our perceptions of life. Carl Linnaeus, the biologist responsible for formalising taxonomy, described the order of fungi as ‘chaos, a scandal of art.’

“Are the fungus and photosynthesiser of a lichen really individuals, though they have no autonomy or capacity for independent life?”

Lichens are one of the best examples of the uniqueness of fungal identity, as a lichen is in fact not a single organism. These humble, pale green structures, often seen coating the bark of trees, are in fact not a single organism. Lichens form between the interaction of a fungus and its photosynthetic partner, either algae or cyanobacteria. Lichens are an exaggerated example of symbiosis, the term for the intimate association between two organisms of different species.

Before the discovery of lichens, evolution was framed solely through competition between organisms, but lichens prompted scientists to acknowledge that organisms of different species can coexist for mutual benefit, to such a degree that there appears to be no separation between them. It can even be argued that the fungus and photosynthesiser components of a lichen are not distinct individuals.

Emergent properties, characteristics that arise from the interaction of components, rather than the individual parts themselves, are a defining feature of complex life. The classic traits of lichen, from their branches and leaf-like structures, to their ability to survive at extreme temperatures, arise only from the interconnected nature of their composite organisms. Are the fungus and photosynthesiser of a lichen really individuals, though they have no autonomy or capacity for independent life? Or is the lichen, this composite organism, the individual, with unique traits arising from the interplay between its two constituents?

“It is easy to describe this relationship as animals ‘farming’ a more primitive, seemingly plant-like organism”

A similar logic applies to organisms slightly closer to us on the family tree – leafcutter ants, social insects that have staked their survival on fungi cultivation. Their life’s work is to bring back leaves to their nest, not for their own nourishment, but to feed the fungi that the ants will then sustain themselves on. Through our human eyes, it is easy to describe this relationship as animals ‘farming’ a more primitive, seemingly plant-like organism.

However, it could just as easily be seen as the other way around – fungi ‘farming’ ants to bring them nutrients, and then providing the ants with a food source after they’ve sufficiently fulfilled their duties. In reality, both organisms are equally dependent on each other. The obligate symbiosis observed between leafcutter ant colonies and fungi is not unlike that between the photosynthesiser and fungus of lichens; both organisms dependent on their symbiotic partner for survival. The further we look into fungal relations, the harder it is to ignore the threads that connect ‘individual’ organisms, blurring the lines between them.

“If separated from their tiny symbionts, cows would be unable to acquire nutrients from their food”

It’s not just fungi forming such close ties with other forms of life. Plant material like grass is notable in that it cannot be broken down by any mammalian species – yet cows are able to grow to hundreds of kilograms eating it almost exclusively. The mechanism behind this impressive feat lies in another inextricable symbiotic relationship, this time with bacteria and other microbes. In the rumen, a large fermenting vat that makes up one of the four chambers of a cow’s stomach, symbiotic microorganisms convert the tough cellulose of grass to useful organic compounds to fuel the animal’s metabolism. When the microbes die, they are digested by the cow’s enzymes and this microbial protein eventually becomes our beef. If separated from their tiny symbionts, cows would be unable to acquire nutrients from their food and starve. This prompts the question of if our concept of cow – a large herbivorous mammal able to turn grass into muscle – can exist without the invisible microbiome that each animal contains. Can we really say that the cow has an individual identity without its symbiotic partners?

While cows are the archetypical example of microbe-mammal mutualism, this symbiosis is observed across mammalian life – us included. Scientists estimate that each individual is coated in trillions of microbes - the vast majority of which are harmless or even helpful. And research suggests that these microbes are intricately linked to mood via the gut-brain axis, thus arguably influencing personality and identity. Throughout scientific history, symbiotic relationships have been perceived as exceptions to evolution – outliers in the ruthless, competitive world of natural selection. But the complex web of fungal interactions can prompt us to think deeper about the blurry line between organism and ecosystem; whether that’s within a leafcutter ant colony, or in the guts of the cows grazing along the Cam. So, the next time you look in the mirror, ask yourself - how different are you really from a lichen?

Comment / College rivalry should not become college snobbery30 January 2026

Comment / College rivalry should not become college snobbery30 January 2026 News / Downing Bar dodges college takeover31 January 2026

News / Downing Bar dodges college takeover31 January 2026 News / Cambridge for Palestine hosts sit-in at Sidgwick demanding divestment31 January 2026

News / Cambridge for Palestine hosts sit-in at Sidgwick demanding divestment31 January 2026 Science / Meet the Cambridge physicist who advocates for the humanities30 January 2026

Science / Meet the Cambridge physicist who advocates for the humanities30 January 2026 Features / Are you more yourself at Cambridge or away from it? 27 January 2026

Features / Are you more yourself at Cambridge or away from it? 27 January 2026