Cambridge’s very own Man of Steel

Dhruv Shenai talks to Cambridge materials science professor Howard Stone about the future of the UK steel industry

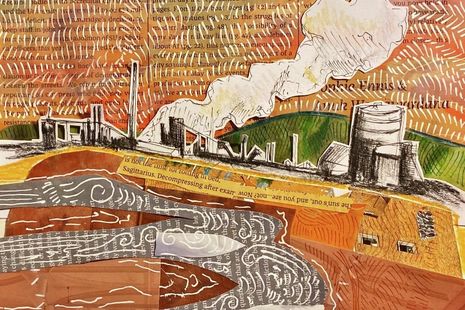

Walking along the Morfa beach in Wales, the sun sinking behind the clouds, you turn to face the peaceful city of Port Talbot. Towering in the foreground is the Port Talbot Steelworks. For the past 70 years, this has been a centre for UK Steel production. Now, its future is on the line, with the last blast furnace falling silent in 2024.

But this apparent loss gives a unique opportunity to some in Cambridge. Howard Stone is the Tata Steel Professor of Metallurgy – a role endowed by Tata Steel, the Indian multinational company which owns the Port Talbot plant. He is investigating the science behind high-recycled-content steel, which could finally enable a cleaner, more competitive steel industry in Port Talbot and the rest of the UK.

It all comes down to Tata Steel’s initiative to upgrade their plant to electric arc furnaces. These furnaces specialise in recycled steel and could make the UK produce sustainable steel. However, the science behind high-performance recycled-steel remains unknown, which is where Howard comes in.

I was intrigued by the significant interest a foreign company was showing in British steel, and so naturally the first question I posed to Stone was: “Why are Tata investing in UK steel?”

“You don’t spend £750 million on a whim.”

I was met with a strong gaze. “You don’t spend £750 million on a whim.” This £750 million, added to a £500 million grant from the Government, is the total investment from Tata Steel on Port Talbot. “Scrap steel has become a global issue. The demand for arc furnaces will only increase. This £1.25 billion investment will secure Port Talbot’s future.”

Currently, the steel industry contributes 14% of the UK’s manufacturing greenhouse gas emissions and around 2.8% of energy-related CO2 emissions. The Tata Steel initiative is aligned with a vision of reducing the emissions of the industry by up to 90% by 2050, with an estimated 50 million tonnes of direct emission reduced in the next decade by the plant alone.

The UK serves only 0.4% of the global steel market, so it simply cannot outproduce other countries. By finding a way to recycle scrap steel, we can make the steel we produce more environmentally friendly, and therefore more appealing. Currently, the UK exports approximately 8 million tonnes of scrap steel annually for other countries to recycle, incurring additional transport costs and emissions. It is time to try something new.

“It’s one of the most exciting times to be a metallurgist. A once in a generation opportunity to redefine the way that steel is made in this country while still meeting the demands of the country.” Though the money and energy are in the right place, is the science?

“It’s one of the most exciting times to be a metallurgist - a once in a generation opportunity to redefine the way that steel is made”

The electric arc furnaces primarily take in recycled steel. However, the more you recycle steel, the more impurities like copper and tin accumulate, which catastrophically ruin the properties of the steel. “Car bodies, food packaging […] the tolerance for residual elements in these uses are very tight. But if we want to be efficient, we can’t just avoid the nasty materials, you have to use all of the scrap,” says Howard.

For Howard, that means being pragmatic. By defining clear grades of steel quality, he hopes to match their properties to their ingredients and processing route, and therefore provide the recipes for companies to produce the right quality steel with the highest amount of scrap.

This relies on open-source data, aggregating the right information into something like a rule book. Unfortunately, steel metallurgy is incredibly complex and the science behind how combinations of dilute impurities affect the properties of steel is not well known. However, with the scrap consumption from the steel sector set to triple by 2050, this research is a necessary step for the UK.

Clearly, the government agrees, as the EPSRC (Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council) decided to work with Tata and the University to fund research with Howard. With his new team, he hopes he can find ways to be smarter about steel production.

In the short term, Port Talbot’s shutdown has disrupted the local community. Around 2800 workers were made redundant last year. Though Tata insists that 5000 jobs will be preserved with the new plant, it begs the question of what the steel industry will look like in the future.

For Howard, the future will be one of hope: “we have to make this work, because the alternative is we’re stuck with the current carbon intensive methods. Let’s make this a reality.”

Comment / College rivalry should not become college snobbery30 January 2026

Comment / College rivalry should not become college snobbery30 January 2026 Features / Are you more yourself at Cambridge or away from it? 27 January 2026

Features / Are you more yourself at Cambridge or away from it? 27 January 2026 Science / Meet the Cambridge physicist who advocates for the humanities30 January 2026

Science / Meet the Cambridge physicist who advocates for the humanities30 January 2026 News / Cambridge study to identify premature babies needing extra educational support before school29 January 2026

News / Cambridge study to identify premature babies needing extra educational support before school29 January 2026 News / Vigil held for tenth anniversary of PhD student’s death28 January 2026

News / Vigil held for tenth anniversary of PhD student’s death28 January 2026