Rock and code: Cambridge AI vs landslides

Haoyang Huang explores how a team from the Department of Earth Sciences are transforming disaster response

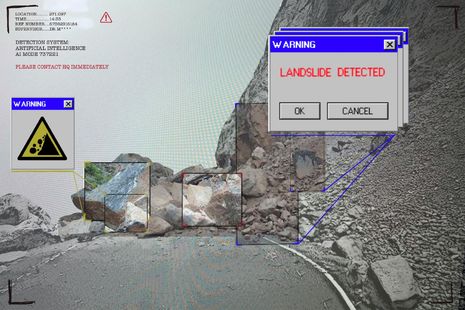

Landslide is a significant global hazard, killing thousands and affecting millions worldwide each year. After disasters, aid workers rely on satellite images to see where roads are blocked and villages cut off, though spotting slides by eye can be time-intensive. Now researchers at Cambridge’s Department of Earth Sciences, led by Lorenzo Nava, are exploring how new image-processing techniques using machine learning can help identify landslides quickly and accurately.

When landslides strike in mountainous and remote regions, satellite images are often the first resource that emergency workers check. However, manual analysis of these satellite images can be painstaking and time-consuming – a process as tedious and slow as revising reading materials for Tripos exams. To aid with this scanning process, Nava’s team have developed machine-learning algorithms capable of identifying landslides quickly, accurately, and autonomously. “In high-stakes scenarios like disaster response, trust in AI-generated results is crucial” Nava explains. “Through this challenge, we aim to bring transparency to the model’s decision-making process, empowering decision-makers on the ground to act with confidence and speed.”

“Manual analysis of these satellite images can be as tedious as revising reading materials for Tripos exams”

This AI-powered detecting system uses neural networks as its machine learning model, mimicking the human brain’s complex functions to recognise patterns. By feeding the system thousands of data points – from stable slopes to fresh slide scar – the AI learns to find a potentially deadly slide.

Identifying landslides often relies on two kinds of satellite information: optical images and radar data. On their own, each type of data has gaps. When thick cloud blocks the sky, traditional optical satellites are blind. Radar satellites, by contrast, can see through darkness, though the information they provide is often more difficult to interpret. AI takes radar’s all-weather persistence and optical imagery’s sharp boundaries, and stitches them into a rapid map of thousands of landslides, producing a more reliable picture.

“AI takes radar’s all-weather persistence and optical imagery’s sharp boundaries, and stitches them into a rapid map of thousands of landslides”

Beyond improving the system’s accuracy, Nava explains that the next step will involve shedding light on the algorithm’s process. “AI can feel like a black box. Its internal logic is not always transparent, and that can make people hesitant to act on its outputs,” he said. Making the tool’s reasoning visible will mean responders can have a better understanding of the data and increase trust in the results.

The Cambridge team isn’t the only pit crew in this AI race against landslides. Researchers from NASA and the US Geological Survey (USGS) have built an open-source landslide-detecting system that segments satellite photos into “objects” and classifies them with machine learning. Transfer-learning pipelines, which adapt the models for new landslide detection tasks, have also been employed.

If disasters hit now, automation is already being deployed. During Haiti’s earthquake and accompanying tropical storm Grace, multiple groups ran rapid remote-mapping efforts in parallel to give responders a first map of blocked roads and cut-off valleys. Cambridge’s work sits within a growing global lineup that is pushing landslide mapping from taking days closer to hours or minutes.

A striking feature of the project is different fields, AI and Earth Science in this case, coming together to help people. Such cross-disciplinary collaboration addresses complex challenges by taking advantage of the range of techniques and technology available, while facilitating advances in both disciplines.

So the next time the earth shakes, know that there might be a Cambridge-built AI algorithm sounding the alarm – helping people find safer ground, guiding aid workers to the worst areas, and, most importantly, saving lives.

Comment / College rivalry should not become college snobbery30 January 2026

Comment / College rivalry should not become college snobbery30 January 2026 News / Downing Bar dodges college takeover31 January 2026

News / Downing Bar dodges college takeover31 January 2026 News / Cambridge for Palestine hosts sit-in at Sidgwick demanding divestment31 January 2026

News / Cambridge for Palestine hosts sit-in at Sidgwick demanding divestment31 January 2026 Science / Meet the Cambridge physicist who advocates for the humanities30 January 2026

Science / Meet the Cambridge physicist who advocates for the humanities30 January 2026 Features / Are you more yourself at Cambridge or away from it? 27 January 2026

Features / Are you more yourself at Cambridge or away from it? 27 January 2026