The next Covid-19: why future pandemics are ‘a certainty’

Ellie Robinson explores possible contenders for the next outbreak

Prof Sir Chris Whitty has warned a future pandemic as big as Covid is “a certainty”. Given the widespread and devastating health, social and economic impacts of Covid, it is important that scientists have a detailed understanding of possible future threats.

The World Health Organisation publishes an ongoing list of infectious diseases prioritised for research and development due to their risk value. This prioritises those diseases with the highest epidemic potential and/or those with insufficient countermeasures currently in place. The majority of newly emerging diseases, and all of those in this priority list, are zoonotic (ie. originated from animals), as was the case with Covid-19. As climate change and human destruction of animal habitats force animals and humans into closer proximity, incidents of these diseases transferring into humans are likely to increase in frequency, and their pandemic-potential is exacerbated by increasing global travel.

Influenza

Whilst 4 of the 5 viruses responsible for pandemics since 1900 have been influenzas, flu does not feature on this list, as the virus is well-understood and there are now “established control initiatives”. Nonetheless, it remains a virus of concern due to its short incubation period (the time between when a person becomes infected with a virus and when they start showing symptoms) and rapid mutation rate (which is related to how quickly the virus evolves). RNA viruses, including influenzas, coronaviruses and HIV, are considered the “inner circle of pandemic threats” due to their ability to mutate faster than viruses which use DNA as their genetic material, and therefore more easily evade existing immunity. In the UK, flu outbreaks come round annually, taking 10,000 lives a year. The constant emergence of new variants allows the virus to stay ahead of immunity, posing issues in the development of vaccines, which are currently only around 50% effective.

"RNA viruses are considered the "inner circle of pandemic threats"

Coronaviruses

Multiple coronaviruses, so named due to their ‘crown’ shape, are present on the WHO watchlist. Unsurprisingly, Covid-19 remains a research priority, as well as Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS-CoV) and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), two coronaviruses which caused large-scale epidemics in 2015 and 2002 respectively. However, some recent research indicates that immunity from the Covid-19 pandemic also reduces the risk of a SARS or MERS pandemic in the years to come.

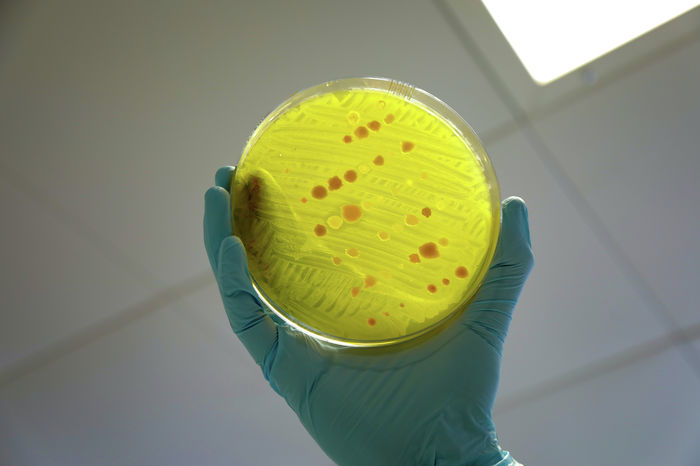

Haemorrhagic fevers

Whilst global pandemics in the last century have tended to be respiratory, it is risky to assume that the next pandemic will continue this trend. There are five “haemorrhagic fevers” (HF) on the WHO priority list for research. This is a group of diseases characterised by fever, bleeding and potentially significant organ system and cardiovascular damage. Haemorrhagic fevers are predominantly localised in West Africa and Asia, and in places with close proximity between humans and certain animals, often rodents. Ebola virus is perhaps the most widely known of these diseases as a result of the highly publicised, deadly epidemic that occurred in West Africa in 2014. Ebola had worrying pandemic potential for a while due to its rapid spread across multiple countries but, thankfully, it was brought under control and there are now two licensed vaccines.

"If we have learnt anything from Covid, it is quite how important it is to have an adequate pandemic preparation plan that has built on the lessons of the past"

Tick-borne diseases, such as Rift Valley fever and Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever (CCHF), are highly climate-sensitive, as warming temperatures are implicated in the lengthening of tick seasons and increasing the abundance of ticks. CCHF has a case fatality rate of 10-40% and is endemic to Africa, the Balkans, the Middle East and many parts of Asia, with epidemics putting pressure on health services. However, as climate change leads to increased temperatures in temperate parts of the world, the risk of infected ticks spreading across a wider geography becomes more likely. Lassa fever, a HF endemic to West Africa, is spread through contact with infected rodent faeces which is worsened by cases of extreme flooding or storms. Nipah virus is the final HF of high concern, particularly due to its mortality rate of 40-75%. Originating in bats, Nipah virus has caused outbreaks across Asia, and there is currently no known cure. The concern in terms of pandemic potential comes if outbreaks of these diseases are shown to have a high ‘r rate’ (an indication of how infectious a disease is), allowing them to spread beyond places in close proximity to the initial infected animals. Measles, for example, has an r-value of 15, meaning that each case is likely to infect 15 more people in an unvaccinated population. Thankfully, vaccination protects the majority of us from this virus, but if an HF virus had a similar r-rate, the results could be catastrophic.

Disease X

The final disease on the WHO’s priority list is ‘disease X’, allowing for the potential that the next pandemic is a disease that scientists do not know or expect, that our bodies have never encountered. Covid-19, a ‘disease X’ itself, highlighted how new viruses can so quickly emerge, adapt and spread, and so attention to preparing for ‘disease X’ is essential. If we have learnt anything from Covid, it is quite how important it is to have an adequate pandemic preparation plan that has built on the lessons of the past. The UK went into March 2020 with an action plan designed for dealing with an influenza pandemic, with limited consideration given to containment measures, contact tracing or lockdown measures. It became only too clear that this was not sufficient for the quite different pathogen that Covid-19 proved to be. As Prof Sir Chris Whitty also recently argued, pandemic preparation and resourcing - such as having sufficient NHS surge capacity and intensive care bed provision - is a “political choice”. A future pandemic may be inevitable, but we have control over how we choose to prepare for and deal with it.

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026 News / University Council rescinds University Centre membership20 February 2026

News / University Council rescinds University Centre membership20 February 2026 News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026 News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026

News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026 News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026

News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026