But Is It Science?

Grace Blackshaw follows last week’s article with another well-illustrated tour through just some of the intersections where, this time, art inspires and informs science.

The first part of this series looked at how science can influence art, which is the form of the relationship we are most familiar with. However, it is not the whole story. In this article, we ask if the relationship ever works in reverse. Can art influence science?

It is virtually impossible to make it through the UK education system without being familiar with the acronym STEM. Since the aftermath of the 2008 financial crash, the UK government has pushed these subjects in schools in an attempt to ‘grow a dynamic, innovative economy’.

While this STEM focus has had clear benefits, it has not been implemented without collateral. A 2015 report from Warwick University revealed that between 2010 and 2013, the number of students taking GCSE Design and Technology fell by 50% and the number of art teachers by 11%.

Some experts now advocate shifting the focus from STEM to STEAM, incorporating art into science and technology education and highlighting the importance of creativity in all industries.

In a similar vein, the examples below explore how art can influence science and technology.

Science Illustration and Darwin’s Finches

Science illustration comes first because the role of art in science is pretty apparent. The work of science illustrators is all around us, from science textbooks to museum exhibits to posters in GP surgeries. The saying goes ‘a picture is worth a thousand words’ and this is particularly true when it comes to explaining complicated scientific concepts.

“Gould’s knowledge and sharp eye... played a key role in the development of the theory of natural selection”

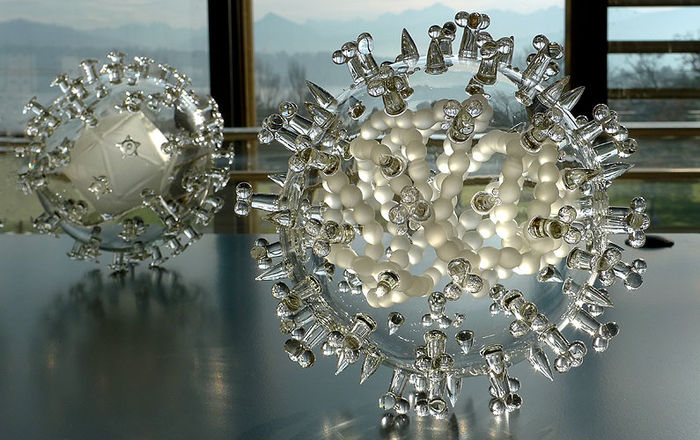

Medical illustrators are one of the most common specialisms and often depict biological processes, internal anatomy and surgical procedures. Paleoartists use scientific evidence to depict prehistoric life and are the main reason young children can identify the difference between a tyrannosaurus and a stegosaurus.

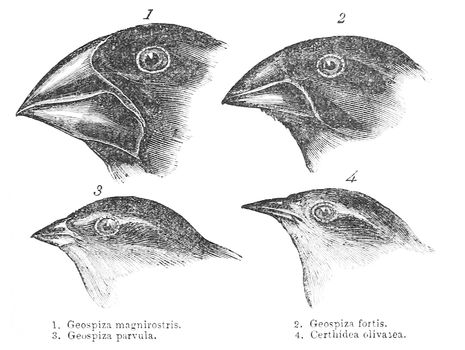

While Charles Darwin’s theory of Natural Selection is well known, the role of John Gould in its development is less so. John Gould was a 19th century British artist and ornithologist, someone who studies birds. In 1837, having returned from his second voyage, Darwin presented his bird specimens to the Zoological Society of London. Gould studied the specimens and concluded that there were in fact 13 different species of finch, not the 6 Darwin had originally thought.

Darwin had not accurately recorded the islands each specimen originated from, but with the help of Captain FitzRoy, he reconstructed his journey and found that species differed between islands. Gould’s knowledge and sharp eye, honed by years of meticulous sketches and scientific illustrations, is thought to have played a pivotal role in the development of the theory of natural selection.

Cubism and Einstein’s Theory of Relativity

At first glance, it is hard to imagine a link between the Cubism Movement and Einstein’s Theory of Relativity. Cubism is an artistic movement, pioneered by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque and said to have begun in 1907. Artists used multiple vantage points to deconstruct objects and represent them in geometric forms.

“Bohr’s work on particle-wave duality was inspired by Cubist treatment of space and perspective.”

Einstein’s Theory of Relativity came in two instalments: his Theory of Special Relativity in 1905 and his Theory of General Relativity in 1915. Special Relativity relies on two key principles: first, that the laws of physics are the same for all inertial frames and second, that the speed of light in a vacuum is constant, regardless of the observers’ relative motion. This fundamentally changes our understanding of the universe and leads to the space-time continuum, in which the universe has four dimensions – three of space and one of time.

Most obviously, these two developments occurred at a similar time. However, the art historian Paul Laporte believed the similarities went far deeper. In his 1945 essay entitled Cubism and the Theory of Relativity, Laporte argued that, “In both, the old mode of paying attention to body or mass while taking the manner of observation for granted, was abandoned. Instead, attention was paid to relationships, and allowance was made for the simultaneity of several views.”

While no one is suggesting a causal relationship between cubism and relativity, both Arthur I Miller and Christophe Schinckus argue that the artistic movement could have had an even more direct impact on Niels Bohr and the development of his Complementarity Principle, describing particle-wave duality.

Bohr was interested in Cubism, had Metzinger’s cubist painting La Femme au Cheval on display in his home and is said to have read Metzinger’s 1912 book On Cubism. Miller argues that Bohr’s work on particle-wave duality was inspired by Cubist treatment of space and perspective.

A. Michael Noll and AI-Generated Art

A. Michael Noll is an American engineer and an early pioneer of computer art. He began experimenting with computer art in 1962, while working at Bell Laboratories.

“Creativity isn’t just for humans.”

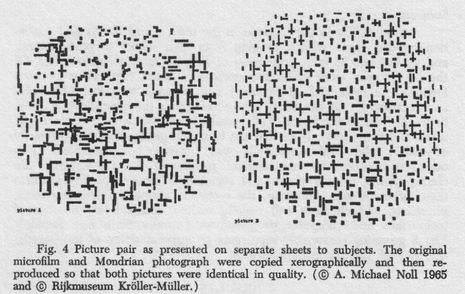

One of his most famous pieces of work formed part of an experiment and was an early implementation of the Turing test. Noll used a digital computer and microfilm plotter to generate a semi-random image similar to Mondrian’s Composition With Lines. The two images were then shown to 100 employees at Bell Laboratories and they were asked to identify which they thought was generated by a computer and which one they preferred. Only 28% of respondents correctly identified the computer image and 59% preferred the computer image.

Noll created many other pieces of computer generated art and his piece A Computer-Generated Ballet is thought to be the first computer generated animation of the human figure in motion.

Moreover, rather than being seen merely as a novel application of technology, the pursuit of authentic computer generated creativity has in fact led to huge developments in artificial intelligence.

Designed by Leonel Moura, the Robot Action Painter uses randomness, stigmergy and chromotaxis to achieve what Moura describes as ‘machine creativity’. It is also able to determine when an artwork is complete and to leave its signature in the bottom-right corner of the work.

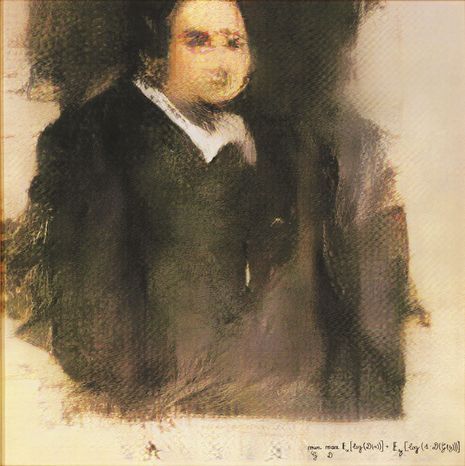

In 2018, Edmond de Belamy was the first piece of AI-generated art to be auctioned at a major auction house. The work was produced by Obvious, a Paris-based collective with the motto “Creativity isn’t just for humans”. (See article thumbnail.)

Steve Jobs and Design

Apple co-founder, Steve Jobs certainly considered himself an artist. When the design of the first Macintosh computer was finalised in 1984, Jobs called the team together and told them, “Real artists sign their work.” Under his direction, everyone who had worked on the Mac signed their name on a sheet of drafting paper. The signatures were then engraved on a metal plate inside every Mac computer.

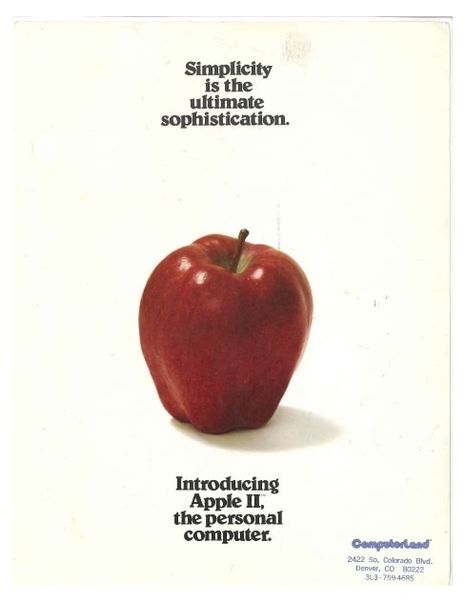

Inspired by the artist Pablo Picasso, the designer Dieter Rams and the Bauhaus movement, simplicity was key to Jobs’ design ethos. Apples’ first marketing brochure made this clear: “Simplicity is the ultimate sophistication.” This pursuit of simplicity shaped not just the exterior of their products, but their inner workings too. Traditionally, industrial designers work within constraints determined by engineers. Jobs reversed the process, approving the overall design of a product and then telling the engineers to make their components and circuitry fit.

Similarly, structural engineers often work within constraints set by architects. At the beginning of her career, Zaha Hadid was labelled the “paper architect” and her sketches considered unbuildable. However, rather than compromise on aesthetics or experimentalism, her designs pushed the boundaries of technology and engineering.

News / Right-wing billionaire Peter Thiel gives ‘antichrist’ lecture in Cambridge6 February 2026

News / Right-wing billionaire Peter Thiel gives ‘antichrist’ lecture in Cambridge6 February 2026 News / Cambridge students uncover possible execution pit9 February 2026

News / Cambridge students uncover possible execution pit9 February 2026 News / Epstein contacted Cambridge academics about research funding6 February 2026

News / Epstein contacted Cambridge academics about research funding6 February 2026 News / Man pleads guility to arson at Catz8 February 2026

News / Man pleads guility to arson at Catz8 February 2026 News / John’s duped into £10m overspend6 February 2026

News / John’s duped into £10m overspend6 February 2026