Colombian Ambassador: ‘We are hoping to take advantage of this new global Britain’

Felix Peckham, looking for a big scoop, is given a masterclass in the art of diplomacy by His Excellence Néstor Osorio Londõno

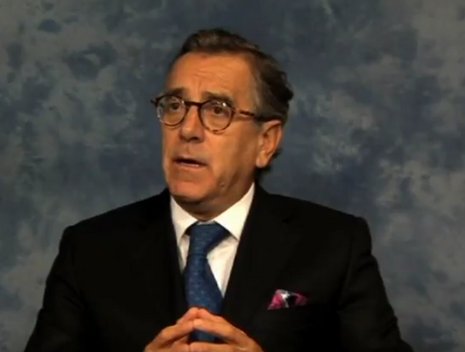

Dapper in a pinstripe grey suit and flowing grey locks, and bearing a slight resemblance to Hugh Laurie, the Colombian ambassador to the United Kingdom stands in stark contrast to his dishevelled interviewer, who is kitted out in the scruffiest imaginable pair of jeans and with a haircut that he had given himself two days earlier. Regardless, His Excellence Néstor Osorio Londõno does not comment on my degenerate style and proceeds to do what diplomats do really well: make you think they are giving you an answer to your question when, in reality, they are not really answering it.

I begin the interview by asking Osorio whether he believes that the British electorate made the right decision in voting to exit the European Union, and if he thinks the Prime Minister has handled the exit process appropriately and effectively.

“We hope we can increase and go from the basis of the free trade agreement we have with the European Union, to have a better agreement with the United Kingdom”

“We [Colombians] have always been very much in favour of the multilateralism of the joint forces of countries to make progress,” he tells me. “So we were a bit worried and shocked to see the European community enter into a period of crisis. There are many reasons to explain that crisis of course, and those that promoted Brexit have good reasons – if there is no reform, there is no point of us staying there”.

He continues: “In terms of explicit effects to the external world, we are in a position to look to the future and capitalise, in the sense that we hope we can increase and go from the basis of the free trade agreement we have with the European Union, to have a better agreement with the United Kingdom. Since [Colombia and the UK] are very good partners, we are hoping to take advantage of this new ‘global Britain’ to improve and develop our relationship.”

A very diplomatic answer. And Osorio continues in that form as I push forward in my efforts to ask potentially tricky questions. Indeed, having discovered the fact that the Colombian embassy in London occupies the same building as the Ecuadorian embassy, I pivot into a question about whether Osorio, and his country, perceive Julian Assange (of Wikileaks fame, currently seeking diplomatic refuge in the Ecuadorian embassy) as a hero or an enemy of the American people. Smoothly, he informs me: “We have not taken any position on this matter. It is an Ecuadorian problem. We don’t get involved in that.”

Another avenue closed off, but surely I can get something out of Osorio on the new American president. Referencing the recent news of Trump’s phone call with the Australian Prime Minister, Malcolm Turnbull, in which the newly elected president was reportedly able to showcase his antagonistic and unconventional approach to diplomacy, I ask Osorio to what extent he believes that Trump’s presidency will change international diplomacy.

“I think that the new administration, and the new approach from the United States, is introducing tremendous transformation in the way that diplomacy is conducted,” he says. Again, he is telling me a lot while telling me a little. “The way he has been pronouncing his policies and the attitude of the United States – that is, protectionism and America first – they have put this conquest of the past 50 years, of multilateralism and the working together of countries, in total jeopardy.”

“We are very careful and wary about how Trump is going to develop a Latin American policy, if such a thing can exist”

I try to push him further, homing in on Trump’s approach to Latin America. And again, Osorio – who has served as Colombia’s ambassador to the UK since February 2014 and also held the position of President of the UN Security Council in 2011 – is ever the seasoned diplomat, refusing to say anything that could be considered directly critical even if there is something underneath it all. “So far with Latin America, and with Mexico and with building the wall, this is again a very negative approach,” he admits. “It could create for Latin America a very awkward situation in which we are in solidarity with Mexico in the sense that bridges, not walls, have to be built”.

Looking to make my journalistic break by convincing Osorio to disclose that Trump had accused the Colombian President, Juan Santos, of being a ‘bad hombre’, I ask Osorio if the Colombian and American presidents had spoken on the phone.

“They have,” he says. My excitement builds, though it is almost immediately dealt a crushing blow: “it was very courteous and a way of saying we will work together. [America] is one of our most important partners – not a predominant one – but important. Of course, we are very careful and wary about how Trump is going to develop a Latin American policy, if such a thing can exist. We will see”

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026 News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026 News / University Council rescinds University Centre membership20 February 2026

News / University Council rescinds University Centre membership20 February 2026 News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026

News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026 News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026

News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026