Nostalgia in Music

Columnist Joseph Krol sheds light on the the topic of Nostalgia in Music through vivid descriptions of yearning

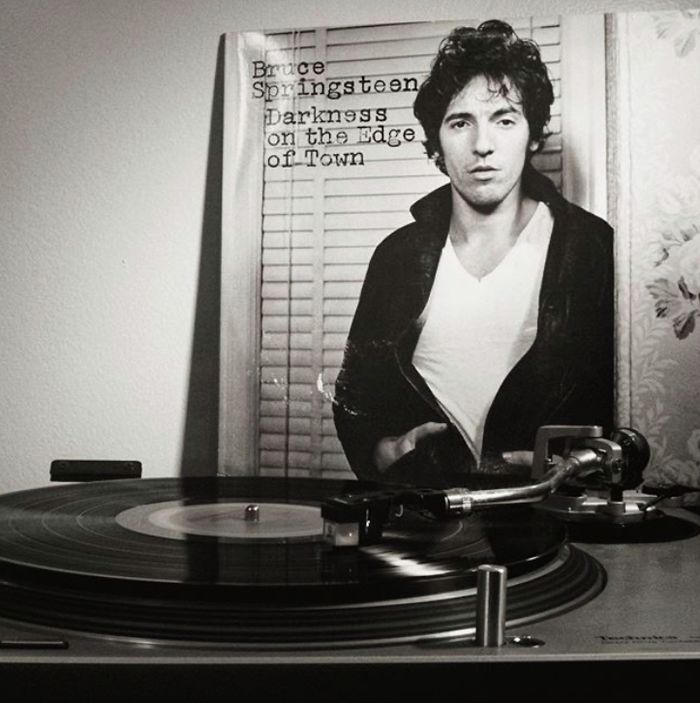

Nostalgia, some wit wrote, is not what it used to be; indeed, recently it seems to have become an increasingly powerful part of the zeitgeist. It was inevitable that nostalgia would become one of the dominant emotions of lockdown: in a year in which the present has come to lack any distinguishing features, the past has found a way to rise up and fill the gap.

The exploitation of nostalgia is as old as the concept itself. This recasting can take various forms – say, the deliberate reuse of older sonic structures, or direct lyrical reference to some particular point in the past. The Weeknd’s recent hit ‘Blinding Lights’, and Dua Lipa’s latter-day work on the aptly-named Future Nostalgia, are both very creditable instances of the former, both leaning on an unremembered eighties. Anne-Marie’s song ‘2002’ is a typical example of the latter, its chorus giving the listener little more than a list of random cultural denominators. It is sobering that most of the people on the relevant dancefloors nowadays are young enough that for them '2002' can hardly hold any cultural meaning at all.

What is usually presented to us as ‘nostalgic’ music is often hardly anything of the sort. Merely to imitate the past, or worse still to simply point out that it occurred, seems a questionable method to generate nostalgia to any great degree. The trouble lies in the intensely personal nature of the emotion; trying to directly recreate – or rather create – this generalised non-past is unlikely to get beyond the superficial. There are a couple of interesting tracks musicians have taken to get around this problem; the first, and perhaps the more obvious, is by brazenly creating something that is very specifically nostalgic to them, and encouraging listeners to come along for the ride.

Microphones in 2020 – Phil Elverum’s first release in some years under the Microphones moniker – achieves this rather well: the lyrical heft of the record lies in the singer’s evocation of a particular period in his life, around the time he was producing some of his most acclaimed albums. Of course this is self-indulgent, and the lyrics make it clear that Elverum is only too aware of this; but it's almost through this directness that it seems to work. On one level the well-versed listener might be taken back to their own experiences with these earlier albums; on another, the record seems to invite the listener to use the album as a launching point for their own journey into memory. The album encourages this quite clearly, with reflections on ‘the true nature of things’ that, rare in music, actually stand up as poetry, and the unwavering guitar pattern that takes up the first ten-or-so minutes of the album. Features like these are all expressly intended to separate the listener from their current worldly situation, and deliver them to some vague province of the mind.

Another approach, I suppose, is along the lines of Boards of Canada. The work of the Scottish electronic duo has, since the release of their seminal debut Music has the Right to Children in 1998, been called ‘nostalgic’ almost by default, despite the tracks not having much direct similarity to anything else in the musical canon. Another arresting factor is that, in the sense of triggering memories, the album still works decades later – by not aiming to evoke a specific time period, their music retains its potency. A great part of nostalgia arises from time seeming out of joint, when memories start to separate away from their substrate of a ‘known’ past; what better to trigger it than an album at once so unique, and yet so full of almost-recognitions, that it seems impossible for it to have been made in any decade at all?

"A great part of nostalgia arises from time seeming out of joint, when memories start to separate away from their substrate of a ‘known’ past"

That it all works so miraculously well itself adds to the inherent disquiet of the record. Somehow, through a little-divulged suite of studio effects, Boards of Canada succeeded in creating something that seems able to prompt uneasy wistfulness in people of any country, of any time. By being so flagrantly independent of its context, so otherworldly, it ends up providing a fine soundtrack to those fond, dreamlike memories that teeter somewhere near the edge of reality. (But to analyse it on a deep level musically seems dangerous, like picking apart a watch to work out which gear does what: one worries it would not work quite so well ever again).

Of course all this bypasses the uncomfortable truth that the best way to produce nostalgia musically is to release a nondescript chart single and wait ten years. To construct nostalgia, so that it is present from first hearing, admits a few different approaches; it could seem ironic, somehow, these all explicitly rely on producing something that is not of any time at all. I suppose one is not directly constructing nostalgia as such – something all but impossible with such a subjective emotion – but rather constructing favourable conditions for triggering it. But this is still a fine goal: even in half-pasts there is so much to remember.

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026 Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026

Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026 News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026

News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026 Comment / ‘Don’t worry, I barely revised’: the effort behind performative effortlessness11 March 2026

Comment / ‘Don’t worry, I barely revised’: the effort behind performative effortlessness11 March 2026 News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026

News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026