Zoetrope: Small beginnings in Canadian animation

Ian Wang opens his column on the eclectic cinematic realm of animation with the little known but hugely influential works of the National Film Board of Canada – be sure to follow the links to their noted works

Canada’s film industry gets a raw deal. Canada is home to two of the biggest North American filmmaking cities in Vancouver and Toronto, sometimes described as “Hollywood North”, and has produced an array of successful stars and directors, from James Cameron to Ryan Gosling. However, the long shadow of its southern neighbour is hard to escape – most Canadian filmmakers are all too eager to pack their bags for America once they have made a name for themselves, and many of the movies filmed in Canada are actually made by Hollywood studios who just want to use Canadian cities as cheap stand-ins for American ones.

“McLaren’s best-known shorts combine the technical proficiency of a lifelong animator with the giddy glee of toddler’s sketchbook”

There is one exception to this rule – the National Film Board of Canada. In the 78 years since its founding in 1939, this small, blandly-named government agency has produced over 13,000 films and received 74 Oscar nominations, an average of almost one a year. Although it remains little known, the studio’s animation department has been the centre of some of the most imaginative, colourful, and downright bizarre innovations in the history of the medium.

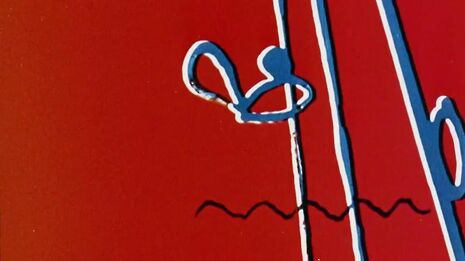

It all begins with Norman McLaren, who joined the NFB in 1941. He was the powerhouse of its animation department for several decades, an experimental filmmaker whose array of shorts might be better described as abstract video art than animation. None of his films is anything close to conventional – most of them have no plot, no dialogue, and no characters. Instead, they work their magic through doodles, squiggles, dots and lines, splashes of paint. Some of McLaren’s best-known shorts combine the technical proficiency of a lifelong animator with the giddy glee of toddler’s sketchbook, as playful and comic as they are visually impressive.

Much of McLaren’s work was actually informed not by visuals, but by sound. In the minimalist Dots, McLaren painstakingly etched a series of blobs, stars, and points directly onto a strip of film. The interesting side effect of this was that a projector could also process those etchings as the film strip’s audio track – you could literally hear what these dots sounded like. McLaren was also inspired by the music of others. Begone Dull Care, which he made with fellow NFB experimentalist Evelyn Lambart, paired the rambunctious piano jazz of Oscar Peterson with a barrage of chaotic, expressionistic colour: jagged lines and vivid textures that flash on the screen for an instant, only to be replaced by the next delirious set of visuals.

Another of the NFB’s innovators was Caroline Leaf. Though Leaf joined the NFB in 1972, she had actually completed most of her innovation before then, as a postgraduate student at Harvard. Leaf had no previous background in animation, but she happened to take a class in it in the late 1960s and decided she wanted a medium with more spontaneity and personality than was allowed by more traditional animation techniques. One day she took a jar of sand from a local beach, poured it on top of an illuminated box and started drawing images with it directly underneath a camera. And just like that, she had invented a brand-new style of animation.

“Images blur and smudge into one another, faces disappear into the shadows”

Sand animation, much like her later invention of paint-on-glass animation, which trades sand for slow-drying paints atop a glass sheet, brings with it an almost dreamlike sense of fluidity and ethereality. Unlike hand-drawn animation, where each image is drawn separately on individual sheets of paper, Leaf’s techniques require the animator to always be working on the same canvas – in other words, to create the next frame, one literally has to move the sand or paint used to create the last frame.

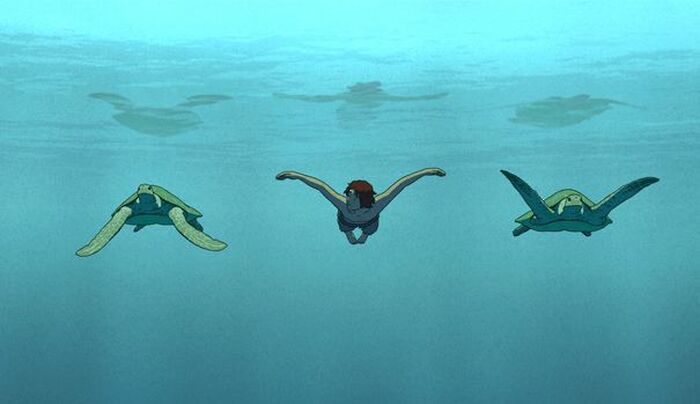

When looking at any of Leaf’s films (I recommend 1976’s The Street), one recognises this immediately. Instead of cutting from scene to scene as in traditional animation, Leaf warps the entire canvas so that one scene transforms seamlessly into the next; images blur and smudge into one another, faces disappear into the shadows, shapes bend and stretch and twist to adapt to a restlessly moving camera. Leaf’s impressionistic new techniques, especially paint-on-glass animation, were hugely influential, and though she only received limited recognition at the time, she paved the way for dozens of other independent animators. One of the best-known paint-on-glass animators, Aleksandr Petrov, ended up winning the Oscar for Animated Short Film for his adaptation of The Old Man and the Sea.

Leaf and McLaren are two of the NFB’s most inventive filmmakers, but there are so many other strange, wonderful, magical shorts produced by NFB animators – I’ve barely scratched the surface in this article. There’s Peter Foldes’s nightmarish 1974 short Hunger, one of the first ever computer-animated films. Then there is Regina Pessoa’s Tragic Story with a Happy Ending, a fairy tale rendered paranoid by its intense high-contrast black-and-white imagery. Finally, there are Jacques Drouin’s Mindscape and Michèle Lemieux’s Here and the Great Elsewhere, both surreal shorts animated with a screen made up of tens of thousands of tiny pins.

With nearly 80 years of history behind it, the NFB’s animation catalogue is a sheer treasure trove of creativity which I encourage you to take a dive into yourself, and see what you find

News / Colleges charge different rents for the same Castle Street accommodation2 March 2026

News / Colleges charge different rents for the same Castle Street accommodation2 March 2026 News / News in Brief: waterworks, wine woes, and workplace wins 1 March 2026

News / News in Brief: waterworks, wine woes, and workplace wins 1 March 2026 News / Climate activists protest for ‘ethical careers policy’1 March 2026

News / Climate activists protest for ‘ethical careers policy’1 March 2026 News / Angela Merkel among Cambridge honorary degree nominees27 February 2026

News / Angela Merkel among Cambridge honorary degree nominees27 February 2026 News / Private school teacher who lied about Cambridge degree barred from teaching27 February 2026

News / Private school teacher who lied about Cambridge degree barred from teaching27 February 2026