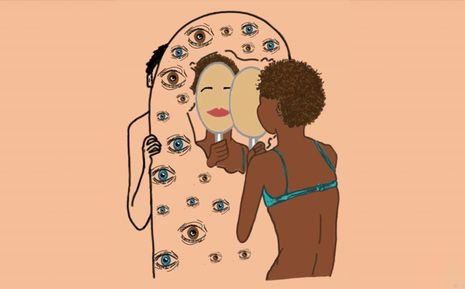

A Black remedy to the male gaze

For staff writer Zoe Olawore, Cambridge has been an unexpected place to find a ‘solution’ to the male gaze, as she shares how the Black community at university has helped her to slowly overcome it

The male gaze is inescapable. So deeply embedded in a woman’s identity. “Even pretending you aren’t catering to male fantasies is a male fantasy”, Margaret Atwood once famously said.

I would always hear the male gaze being discussed as something everlasting within feminist spaces, leaving me apathetic. However, I initially did not realise how heavily underlined the male gaze was by racism. And so, confronting internalised racism was a step towards decentering the male gaze.

“Being one of the few black girls in my grammar school, I was hyperaware of my differences”

Growing up in a racially monolithic area in Essex, my ideas of beauty were narrow. I saw beauty as akin to whiteness and such a belief was only exacerbated by my time spent in school. Despite going to an all-girls school, I was still overly concerned with appealing to the male gaze. Being one of the few black girls in my grammar school, I was hyperaware of my differences. Consequently, every month I would lather a relaxer on my hair even though this meant my scalp was burnt. My hair is an integral part of my identity: I saw, and still see, my hair and my appearance as two heavily interconnected elements. Because I treated my hair as the axis upon which beauty would rest, this was the first ‘problem’ I wanted to deal with: my hair being coarse and short. And when I eventually stopped relaxing my hair, this was not some sort of revolutionary act. I had simply taken to my mum’s threats that I would be bald by my wedding day.

Apps like Tik Tok only made my discomfort grow. Before I was on ‘Black Tiktok’ (thank God for that) my For You page was overcrowded with videos of white women who had gone viral for their appearance. Although the general attitude towards race at this time was unconsciously post-racial, I noticed the general trends in what appearances were deemed favourable. This was white or white-passing skin, type 1-2 hair, and thin noses. The male gaze was white and favoured what looked white.

When getting ready to move to university, I only expected my feelings to get worse. Before October, I spent hours researching different ways to do makeup, and spent hundreds of pounds - dismissing my Mum’s shouting - because I felt obliged to do the most to feel pretty in a white space like Cambridge. I felt like I was running a race where everyone else was at the starting line and I, being behind them, had to compensate.

But more recently, it dawned on me that perhaps this was not a race I had to compete in. This may be idealistic of me, but perhaps the male gaze is an experience every woman is equally subject to. Nonetheless, I began to imagine a reality where I actively refused to participate in the fight to feel beautiful amidst structures that naturally disadvantaged me.

“I stopped seeing my blackness as a barrier to feeling beautiful”

A few weeks into my first term these imaginings began to materialise. The obsession that I had with the male gaze dramatically decreased. My feelings of liberation, though small, did not stem from an individual effort. It did not decrease by spending more hours on my hair or more time on my makeup. Rather, it was through the time I spent with my own community.

My struggle with the male gaze could not be individualised when I was up against issues that are systemic.

Quite naturally, I spent time with other black people in and outside my college perhaps to avoid feeling like an outsider in Cambridge. Surrounding myself with other black women, in particular, felt like a form of self-representation. By seeing ‘myself’ more and more I began to feel more comfortable in my own skin. Similarly, being around black people who were assured about their appearances made me realise I had no reason not to be. Slowly I stopped seeing my blackness as a barrier to feeling beautiful: my curvy nose, darker skin, and thicker hair were not parts of myself that deserved my hate. Nor did I engage in some sort of artificial praise of my features: I just started to see parts of my body as normal since I saw them all around me.

But all of this is not to purport that I am now completely comfortable with myself. Eurocentrism and the male gaze is not something that can be escaped by having a diverse friendship group. Similarly, I cannot act as if my community does not perpetuate a beauty standard of its own, a standard charged by colourism and texturism. Nonetheless, I am proud of the progress that has been made.

Cambridge was the last place I had expected to find a 'solution' for the male gaze. While liberation from racist notions of beauty by myself was impossible and a 'male fantasy' itself, my remedy could be found within my community. Surrounding myself with other black people - particularly black women - has given me an environment where I can be comfortable with my appearance rather than degrade it.

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026 News / University Council rescinds University Centre membership20 February 2026

News / University Council rescinds University Centre membership20 February 2026 News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026 News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026

News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026 News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026

News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026