Preserving snapshots of Cambridge’s anti-women protests

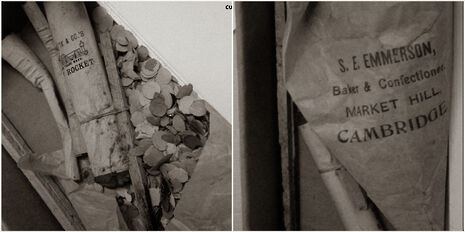

Rockets and eggshells which had been used to victimise women seeking a Cambridge education are now to be digitised in a technically complex process

When the question was first posited in 1897 of whether women attending Girton and Newnham should be granted Cambridge degrees equal in value to those awarded to men, male undergraduates protested by burning effigies of female scholars and throwing fireworks into the windows of women’s colleges.

Now, a series of items collected during the Cambridge street protests opposing admission of women to the University – rockets, confetti, and eggshells from the near-riots – are to be photographed and archived for public record.

In celebration of the 1897 decision, male protesters maimed and decapitated an effigy of a female Cambridge student

Archivist Sian Collins, of the University Library Department of Archives and Modern Manuscripts, said that the materials offer insight into an “extraordinary time”. She told the BBC, “it’s not an eyewitness description or a newspaper report – these were actual items used to victimise people, things that don’t normally survive”.

An entry description of the artifacts detailed how they serve as a “tangible and unusual reminder of the depth of outrage felt by male students in Cambridge” at the prospect of “granting equality to female students”.

When the Senate House vote was first held in 1897 on whether to accept women as full members of the University, female students suffered a defeat of 661 votes in favour and 1,707 votes opposed – a decision which would not be overturned until 1948. In celebration of the 1897 decision, male protesters maimed and decapitated an effigy of a female Cambridge student before pushing the remains through the gates of Newnham College.

It will offer a glimpse into a period of Cambridge’s history malaised by its archaism, where its community was not only lagging behind the curve, but actively – and violently – fighting against it.

A second Senate House vote on whether to grant female students full membership to the University was held in 1921. The repeated defeat of the motion inspired a crowd of male undergraduates to use a coal trolley as a battering ram, smashing and partially destroying Newnham College’s Clough Memorial Gates.

Cambridge University’s history with its female students has been fraught with institutional apathy, and its progression toward equality slow: as men violently opposed the push for equal University status, several women made landmark academic achievements to little acclaim – their Tripos marks not considered comparable to male students who had taken identical exams.

Cambridge was the last university in the UK to grant its female students equal rights, despite having allowed women to attend certain lectures from the 1870s, and to take Cambridge exams from 1881.

The last Cambridge college to fully integrate women did so even later, in 1988, when Magdalene accepted its first cohort of women. In protest of the decision at the time, Magdalene men wore black armbands and flew the college’s flag at half-mast, ‘mourning’ the end to an exclusively male College.

The artifacts from the 1897 protests, currently stored at Cambridge University Library, are to be digitised by a process which may involve the use of 3-D imagery. Cambridge Digital Library announced that it would digitise the items after its entry received a plurality of votes in the Library’s ‘digitisation competition’, where certain objects were voted on whether to be made publicly available online. A Portolan chart of the Aegean Sea, the paintings and drawings of the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, and the ‘Golden Book’ of the Cambridge University Music Club, are also set to be made digitally available to the public.

When the 1897 artifacts were suggested for digitisation by the Cambridge Digital Library, an entry description wrote, “these fragile items bring home how physically threatening it must have felt for these women, who simply wanted their hard work and exam success acknowledged equally.” In providing public access to the symbols of the anti-women riots, the Library offers a glimpse into a period of Cambridge’s history malaised by its archaism, where its community was not only lagging behind the curve, but actively – and violently – fighting against it.

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026 News / Gov grants £36m to Cambridge supercomputer17 February 2026

News / Gov grants £36m to Cambridge supercomputer17 February 2026 News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026 News / CUCA members attend Reform rally in London20 February 2026

News / CUCA members attend Reform rally in London20 February 2026 News / Union speakers condemn ‘hateful’ Katie Hopkins speech14 February 2026

News / Union speakers condemn ‘hateful’ Katie Hopkins speech14 February 2026