In Conversation with Otamere Guobadia

Fashion Editor Muhammad Syed sits down with writer Otamere Guobadia to discuss literature, fashion, and how they serve as guiding philosophies for life

When I first came across Otamere’s work, his writing struck me as sentimental yet analytical. His articles read like academic essays, albeit ones that were accessible but still flowery and poetic. I proceeded to form two suppositions: the first was that he read Law and the second was that he went to Oxbridge. A quick Google search later and both my assumptions were proven correct.

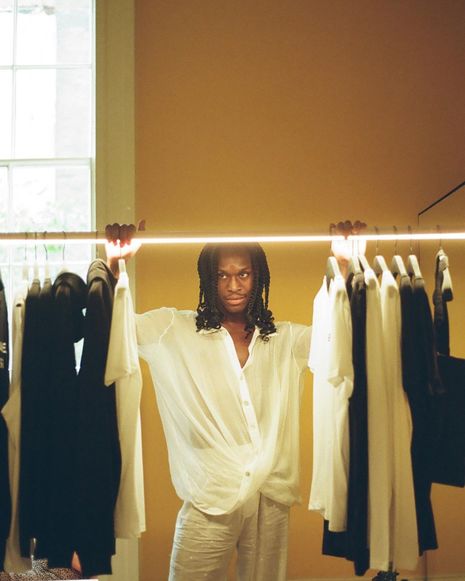

In an age of multi-hyphenates, there are few who embody the term better than Otamere. He is first and foremost a writer, a web show host, a queer activist, a fashion critic, a lover (not a fighter). He epitomises what it means to straddle the fields of fashion, pop culture, queerness, race, and art.

Otamere’s entry into the fashion industry ended as soon as it began. Wide-eyed and hopeful, he entered the hallowed fashion cupboard of InStyle magazine as a fresh Law graduate from Oxford. In a hilariously brilliant piece for WePresent (that I implore any fashion hopeful to read), he writes about his six-month stint living the “Fashion Fairytale”. Where famed shows like Ugly Betty and The Devil Wears Prada sold idealised versions of the fashion cupboard, the stark reality was that it was “a small, windowless box.” It was anything but glamourous.

“Fashion produces a version of myself that feels magnified, confident and complete. It triggers a power within me that was latent.”

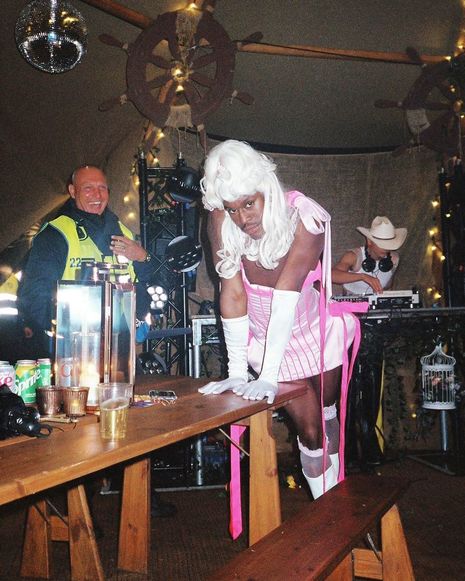

“I think everyone knows the fashion industry is brutal but I guess that is part of the appeal. It draws people in. The risks are exciting but the rewards can be so great that people want to embark on treacherous odysseys. They want to be transformed in the end and that’s what fashion promises people”, he explains. Though his qualms about the industry persist, his everlasting love for fashion remains. He counts Kimberly Ann Hart as the Pink Ranger (who he wrote about extensively for i-D) and Lady Penelope in Thunderbirds as shaping his formative memories of fashion. They served as an entry point, he says, into a love of pink that he has not been able to shake off to this day. As for his favourite designers, Palomo Spain and Mateo Velasquez immediately come to mind. The brands, which both share an ethos to create gender-neutral clothing, have visualised his fantasies even before he has understood them himself. “Fashion produces a version of myself that feels magnified, confident and complete. It triggers a power within me that was latent.”

After stints in both the fashion and music industry, Otamere returned to writing, “the great love and salvation of his life”, and has not looked back since. The rest of our conversation is about literature just as much as it is about fashion, gesturing to how the two intersect. He jokes about being “a trite soft boy” and disarmingly admits that his favourite books are written by F. Scott Fitzgerald, Oscar Wilde, and Virginia Woolf. When discussing the latter, he speaks with greater exuberance. Otamere describes Woolf as a “visionary” who managed to “construct a gender-bending, eternally relevant, fluid character to vicariously live out and speak her love at a time she could not.” Her 1928 classic ‘Orlando’ has been described as the most important love letter in literature, a kind of literary justice free from the shackles of economic and social limitations imposed on women. After all, Otamere perceptively asks, “what is literature if not a means to set the world to rights, the world you cannot have?”

“What is literature if not a means to set the world to rights, the world you cannot have?”

This focus on aesthetics, entangled in the books that he mentions and the clothes that he wears, informs the way he approaches art. His love for dandy-ish, princely clothing is reminiscent of Oscar Wilde’s subversive wardrobe, who I safely assume approves of Otamere’s fashion. The novels he cites – The Great Gatsby, Tender Is The Night, Call Me By Your Name – are beautifully-written pieces of prose that verge on being poetry. They are melodic, rich with figurative language, and fixated on glamour. The same can be said about his own writing. “I think there are many people who find me saccharine and find my writing cloying”, he admits. “And perhaps, they are right. My writing is cloying and I may just be engaging in hagiography but why shouldn’t I? I want to fawn over things and people. That will always be my self-appointed role.”

Indeed, it is a role which he lives up to. I ask him about his favourite creatives, many of whom he considers as friends, which he recites without hesitation: Aidan Zamiri (“fucking dreamscape”), Tom Rasmussen (“the most talented person he knows”), Ib Kamara (“a visionary”), Alexander Pillet (“fiercely analytical and passionate”), Pam Boy (“ridiculous and insane”), Shon Faye (“who will revolutionise the conversation on transness”). As an important member of the creative scene in London with a powerful voice and loyal following, Otamere is a fierce supporter of his community. The kind of friend everybody wants in their corner, cheering them on from the bleachers. I imagine the creative scene to be full of bright young things, akin to the Bloomsbury group of which Woolf was a member. Otamere, however, is quick to correct me by conceding that “it can be cliquey but there is a great deal of specialness and vibrance within the people.”

For Otamere, it seems that all roads lead to his literary heroes. He dresses like Wilde, writes like Fitzgerald, and shares similar thinking to Woolf. But beyond this, he has a tendency to romanticise the present and look back on the past with rose-tinted glasses because, as previously claimed, he is a lover (not a fighter). It is a philosophy for life which he practices but does not promulgate. He recalls his time at Oxford and the fashion industry as periods marred with many difficulties. However, the trials and tribulations he faced were dulled by formative moments that shaped him into some of who he is now.

As our interview draws to a close, I ask him what advice he would give his 18-year-old self. He sighs, takes a pause, and wistfully says: “remember that you have value and are capable. Always continue to fight and reach for something beyond yourself. Also, wear more blush.” His concluding remarks deliver a manifesto to live by, perhaps something we should all get behind. If Woolf could read this, I imagine she would agree.

Comment / Plastic pubs: the problem with Cambridge alehouses 5 January 2026

Comment / Plastic pubs: the problem with Cambridge alehouses 5 January 2026 News / Cambridge businesses concerned infrastructure delays will hurt growth5 January 2026

News / Cambridge businesses concerned infrastructure delays will hurt growth5 January 2026 News / New movement ‘Cambridge is Chopped’ launched to fight against hate crime7 January 2026

News / New movement ‘Cambridge is Chopped’ launched to fight against hate crime7 January 2026 News / AstraZeneca sues for £32 million over faulty construction at Cambridge Campus31 December 2025

News / AstraZeneca sues for £32 million over faulty construction at Cambridge Campus31 December 2025 Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025

Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025