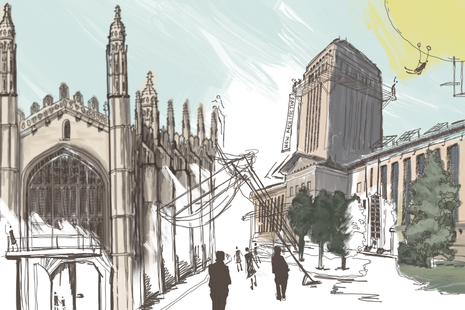

Why Cambridge’s architecture never lives up to the ‘dark academia’ dream

Jessica Leer explores the aestheticisation of Cambridge and its buildings

It is a well-known fact that Cambridge lives in its own bubble; talk to any student and you will know how time moves faster, how the spaces you occupy sit differently. However, we neglect to consider the effect of its buildings on this phenomenon. The city is always rampant with constant construction to maintain the picture-perfect ‘Cambridge’ – but at what point do we lose this ‘dark academia’ dream and instead find ourselves in an elitist bubble, drifting closer and closer to Huis Ten Bosch.

Despite previously being a Tumblr subculture in its own right, the ‘dark academia’ aesthetic rose to fame around 2020 on social media, and considered a lifestyle focused on the pursuit of knowledge and intellect. A quick search would flood you with dimly lit old libraries, overcast autumn days and, most importantly, pictures of Cambridge. Many have criticised the aesthetic for perpetuating overwork, Eurocentrism and elitism.

“This dishonesty to the context of modern Cambridge is why we can never connect wholly with the city; returning home at the end of every term feels like returning to real life”

Visitors to Cambridge are often mystified by the architecture of the city. Just seeing King’s College Chapel can consolidate applications to the university (although I personally credit the North Court of Trinity Hall for mine). But to what extent are our first perceptions of the city misguided? As an architecture student who has spent the last two years in the city, I find that a lot of the details and personality of Cambridge get lost in its devotion to historical remembrance.

We constantly repair old buildings to their former designs, and when we do push for change, it is largely hidden or rejected, like the solar panels on the top of King’s College Chapel. This dishonesty to the context of modern Cambridge is why we can never connect wholly with the city; returning home at the end of every term feels like returning to real life.

When we ignore the larger context of a place, it loses its feeling. Take Huis Ten Bosch, for instance, which was the result of a Japanese architect’s love of old Dutch design. When the design was brought to Japan, it was not taken seriously and is now perceived as a theme park, losing much of the design’s context. Although I respect the preservation of listed buildings, how we initially view Cambridge through an aestheticised reverie soon becomes too hard to maintain.

Cambridge is a beautiful city, not just through its older buildings, but the wider context of new additions to the space. We should celebrate new uses of old spaces, like the way new shops fill older facades in the centre. There is a unique opportunity here; we should not be so hesitant to create something which incorporates both the old and the new. Currently, the city sits in a limbo through the disconnect between its roots and its current students. These interactions of old and new are what reflect our students the most; the contradiction of 100 laptops in a centuries-old lecture theatre creates a unique atmosphere that we do not see elsewhere.

“Our dark academia fantasy, dreamt up while scrolling UCAS, is not possible”

Academia is not generally aesthetic. It is not simply reading old books by candlelight in grandiose libraries, but it is also poring over contradicting online sources an hour before an essay is due, and going head-to-head in a supervision with someone who finished the reading list before term even started. Architecture is much the same: we find something real, something gritty, in the imperfect of it. It is in the ordinary moments that we find the most joy. What we may be searching for in our environment can be found in the everyday interactions we have in these spaces.

As students, we interact with the city on a deeper level than most tourists or visiting school kids. As we explore the city and become fully immersed in its lifestyle, we lose that dark academia dream, not for our own faults but for the fact that our lives no longer reflect that era. We no longer write with fountain pens nor don a long trench coat (except perhaps a select few). Doing those things feels fake or rehearsed; the buildings may suit the activity, but we do not. Our dark academia fantasy, dreamt up while scrolling UCAS, is not possible. However, what is possible is a deeper connection with our academia; we don’t need our ‘-cores’ or ‘aesthetics’ to be able to find inspiration to study. At the end of the day, the buildings may inspire, but the ‘dark academia aesthetic’ pursuit of knowledge is already inherent in all Cambridge students.

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026 News / Law don launches divestment petition12 March 2026

News / Law don launches divestment petition12 March 2026 Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026

Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026 Comment / ‘Don’t worry, I barely revised’: the effort behind performative effortlessness11 March 2026

Comment / ‘Don’t worry, I barely revised’: the effort behind performative effortlessness11 March 2026 News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026

News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026