Minimalism makes a saleroom

Ben Birch explains why commercial galleries are all white cubes

To think about the value of an artwork has become inseparable from thinking about its price. To see an instantly recognisable painting like Renoir’s ‘La Place Clichy’ in the Fitzwilliam Museum is to know that the frame alone costs more money than most people will ever see. Part of the charm of the gallery is this awed sense of rarity. So, it can be a surreal experience to walk into a commercial art gallery where all that is exhibited is available to be purchased. In these commercial galleries, art’s abstracted sense of value becomes a price point. It takes a certain self-possession, an ability to feign deeper pockets and extravagant spending intentions.

“It’s hard to picture a Mondrian dressed up in the gold leaf and swagger of a traditional frame”

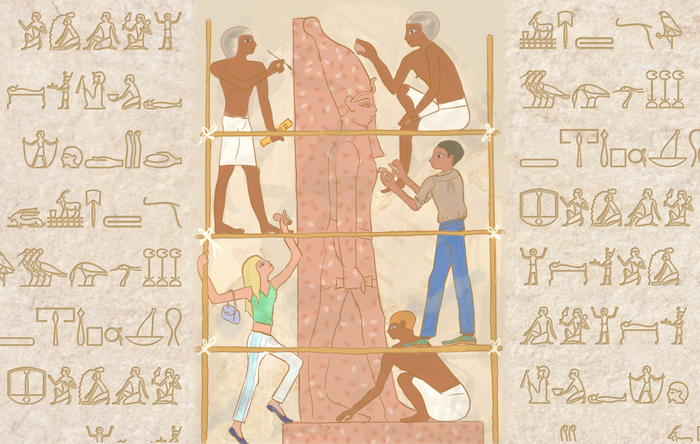

White Cube is a series of commercial galleries with locations in London, New York, Hong Kong, Paris, and Seoul. Founded in 1993 by Jay Jopling, the brand is named after the ‘white cube’ gallery style: white walls, plain flooring, a square room. These gallery spaces are presented as neutral, a non-space which channels focus on to the works of art themselves. As art was becoming more and more abstracted throughout the early 20th century, the white cube style served to emphasise the bolder colours and starker geometric shapes that came to dominate this period. Artists in the Bauhaus and De Stijl movements often insisted on having their works exhibited in these unadorned spaces. Their straight lines and primary colours didn’t work in the grand, old galleries of the 19th century. It’s hard to picture a Mondrian dressed up in the gold leaf and swagger of a traditional frame. The plain walls of the white cube gallery replaced the frame entirely for these artists. Frames used to flaunt value, a sales tactic at which the modernists had begun to turn up their nose. Their disappearance spoke of a radical change in the attitudes that artists were taking towards their work. The white cube gallery rushed the art world into the 20th century.

Jopling’s White Cube comes much later. All of these galleries are done in the white cube philosophy with a focus on exhibiting contemporary artists. The brand gained a reputation for promoting the movement that became known as the ‘Young British Artists’ or YBAs, often exhibiting those who would go on to become some of the most celebrated of their time. Jopling’s galleries continue to represent and sell the works of big names in British art including Tracey Emin, Damien Hirst, and Michael Armitage.

“As much as there is pleasure to be had in simply contemplating these artworks, they’re on display chiefly as commodities”

Currently, White Cube Mason’s Yard are exhibiting the works of Suzanne Song – a Korean American artist for whom this is her first major exhibition in the UK. Upon seeing ’Interfold’, the title of the exhibition, a viewer might be reminded of Rothko: her work has the same kind of blank, imposing force that draws people to him. But she is far more angular, far more Gestalt. Hanging upon the blank walls of White Cube, it’s hard not to be drawn in by the works. Her geometric patterns and subtle changes in hue gives her art a trompe-l’oeil effect. Walking through the unadorned room, Song’s work shifts and quivers as you pass by, moving as you move. Much like the Bauhaus and De Stijl movements whom she might count as her predecessors, the stark white cube style lends itself to her illusions.

There is undeniably something repetitive about walking through a gallery of Song’s works. The patterns are similar, the illusionistic effect is the same, and the colour gradation repeats. But this is no criticism. Constantly re-encountering variations of the same illusions begins to have both a mental and physical effect on the viewer. The gallery space encourages a slowness of pace and thought as you walk through it, moving from one painting to another with no distraction or clutter. The effect is hypnotic.

But all of these artworks are for sale. As much as there is pleasure to be had in simply contemplating these artworks, they’re on display chiefly as commodities. Brian O’Doherty has been a leading critic of the white cube philosophy and its popularity. He writes in his book Inside the White Cube: The Ideology of the Gallery Space:

“Some of the sanctity of the church, the formality of the courtroom, the mystique of the experimental laboratory joins with chic design to produce a unique chamber of aesthetics. So powerful are the perceptual fields of force within this chamber that, once outside it, art can lapse into secular status.”

As O’Doherty points out, there is something worshipful about the white cube style. More than this, there is a sense of separation in each of his examples: the chancel of the church, the judge’s bench, the laboratory’s enclosed sterility. It attempts to present the art as something that is not meant to be lived alongside. Rather, the work is isolated from its contexts in an attempt to appreciate it for its own sake. The great irony here for a commercial gallery is that these artworks are being displayed so that they can be purchased and lived alongside elsewhere, in someone’s home.

“But the trick of those blank walls is that they act as a kind of canvas. Without context, those with deeper pockets can imagine the work of art upon the wallpaper of their own homes”

But the trick of those blank walls is that they act as a kind of canvas. Without context, without museum labels, those with deeper pockets can imagine the work of art upon the wallpaper of their own homes. By contrast, the National Gallery’s ornate and decorative style gives the sense that the art unchangingly exists in this context as it has found a permanent home. So many of Turner’s works have found their place among the claret red walls and golden frames of the Clore Gallery that it is difficult to picture them anywhere else. Cambridge’s Kettle’s Yard houses art as well as being a home for it. In Jim Ede’s cottage, we can get a sense of art in context. It is art that has been lived with, shared among guests and friends. Ede’s curatorial insistence on a vase of yellow flowers to match the yellow lemon in the pewter dish to match a yellow dot in the nearby Miro painting is not neuroticism: it is an effort to live artistically. Ede twinned his home to the art that he loved. In comparison to Ede’s homeliness, the blank walls of white cube galleries seem to take on a fleeting coldness.

In the case of Song’s ‘Interfold’, the works themselves may be impressive, but one leaves the commercial gallery with a sense of its transience: not because the art is forgettable, but because the gallery holds you at an arm’s length. The white cube style of gallery acts as a holding cell for works of art before they find a more permanent resting place. In this philosophy of curation, art exists apart from those who make and experience it. That is not an artistic reality that we must live in, but it is one that has come to dominate newer gallery spaces. More than ever, there is a sense that contemporary art can be reached only by those who can afford it. We cannot really experience Song’s art as part of our own lives unless we’re prepared to reach into our pockets.

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026 News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026 News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026

News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026 News / CUCA members attend Reform rally in London20 February 2026

News / CUCA members attend Reform rally in London20 February 2026 News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026

News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026