Why are we so reluctant to diversify history in the UK?

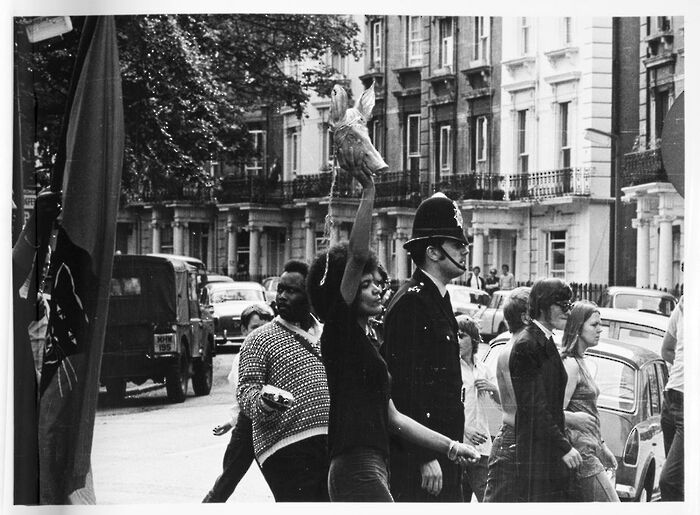

Freya Lewis asks why historians are so hesitant to integrate BME experiences into the curriculum

The study of history in the UK is not in a good place. This much was clear as soon as I arrived in Cambridge: despite being enthralled by the charms and challenges of the University, I was acutely aware that I was struggling to find fellow BME history students and staff. The decolonisation of the history curriculum may seem like well-trodden ground to some – this article is by no means the first to call out the discipline for its Euro-centricity and whiteness.

Is Cambridge doing enough to encourage its students to follow a diversified curriculum?

Write for Varsity and have your say. Just email our Opinion team with a 100-word pitch.

However, the shameful statistics found by Royal Historical Society’s ’Race, Ethnicity & Equality’ report, and the fact that the UK has waited until 2018 to have its first black female history professor, demonstrates that these discourses have not been taken far enough. Now we know that there is a problem, we need to search for its origin to have any chance of finding a solution. We need to ask ourselves the question: why are we so seemingly reluctant to diversify history in the UK?

Part of the reason we approach the diversification of history with such apathy in the UK is that we do not see the need to incorporate BME narratives into a majority-white discipline. Although I by no means want to see the study of BME narratives dominated by white historians, we need to rid ourselves of the expectation that certain histories are only important to certain people. I am sure that many BME students studying history will share the same bemusement I do that, whenever a topic vaguely concerning our heritage or experience arises, the onus is on us alone to care and to understand its importance.

“Decolonising the history curriculum is not just about meeting the needs of non-white students, but about enriching the discipline as a whole”

We are still attached to the outdated assumption that only black academics care about Africa, or that only Asian heritage academics care about Asia and so on. And, if we work on this hypothesis, what’s the point of integrating BME narratives into the history curriculum when only 6.3% of history staff identify as BME, and only a tiny proportion of black students study history at A-Level or university level? The issue becomes imbued with a degree of complacency, due to the assumption that the majority will be unaffected.

However, this is a belief based on entirely false premises. If there is a seeming lack of interest in BME narratives, this is the product of a narrow curriculum which continues to disregard them, not a genuine rule that people only care about histories very obviously related to their own heritage. Decolonising the history curriculum is not just about meeting the needs of non-white students (although this should be a priority considering the diversity statistics recently unearthed by the RHS report) but about enriching the discipline as a whole.

In this respect, I implore a long overdue departure from the mentality that diversifying history will somehow ‘dumb it down’. Pervading our discipline there is a potent, unspoken fear: the fear that the status and academic rigour of history will be somehow undermined by the proper integration of BME narratives.

We see this in the teaching of so-called ‘world history’ in universities – which attempts to cram a plethora of non-European experiences into one non-compulsory paper – and the way in which BME narratives are pushed to the peripheries of the curriculum. The Atlantic slave trade may constitute a tiny sub-section of a British economic history paper, or we may scratch the surface of exploring the concept of ‘race’ in one lecture. Why do we feel the need to ‘other’ these historical narratives and keep them separate from British and European history? Why do we not give them the time and space on the curriculum they deserve?

I for one am convinced that these issues stem from an inherent elitism entrenched in the historical discipline, an elitism we are unprepared to face up to. At present, the inclusion of BME narratives is merely a quick break from reality, an afterthought before we hurry back off to study ‘proper’ history. I hate to disappoint, but this is not an adequate substitute for decolonisation. Painting over the cracks with tokenistic gestures and then scuttling off to our safe havens of elitism will not fix history’s quite frankly alarming diversity problem. We need, as cliched as it may sound to some, ‘real change’: more BME academics, more BME students and more respect for those already in the field.

The study of history in the UK suffers from a crippling lack of diversity and historians seem reluctant to face the problem, due to a long-standing complacency surrounding integrating BME narratives and fears of ‘dumbing down’ the subject. We need to ask ourselves the question: why are we so scared of diversifying history? This will be a reflexive, uncomfortable question to ask: we’ve been up in the ivory tower so long, we’re scared to look down and evaluate ourselves through the lens of race and ethnicity. However, it is what needs to happen. UK historians need to start having earnest conversations about how to seriously improve the diversity of our subject. For too long we have paid lip-service to the issue, or simply recognised that there is a problem and then hoped it would just go away. Students and staff deserve more than that, as does the future of our discipline.

News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025

News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025 Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025 News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025

News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025 News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025

News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025 News / Uni registers controversial new women’s society28 November 2025

News / Uni registers controversial new women’s society28 November 2025