Remembering Diane Keaton

Mia Badby unpacks Diane Keaton’s hallmark journey through Hollywood and beyond

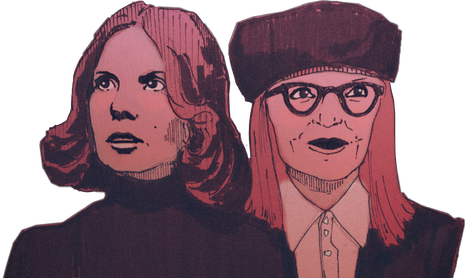

It was love at first sight when Diane Keaton, decked in her waistcoat and bowler hat, first bumbled into frame with all the bashful charm of an actress totally in control of her craft. Her hands are restless, her eyes alert, her smile illuminating: la di da, la di da, la la.

Diane Keaton seemed to have mastered the art of celebrity: a household name, Academy Award winner, and a principal face of 1970s cinema, all while maintaining a veil of privacy. Keaton’s approach to fame was that of a springboard: she wasn’t just an actress, but, as published in a 2023 Guardian interview, a bona fide creative with a passion for photography, collages, architecture, design and even doors. It was for fashion, however, that Keaton became something of an ‘icon’: with her affinity for hats, glasses, and a blend of masculine silhouettes and feminine flourishes – one thinks of her signature coloured gloves.

It all began, as it must, with Woody Allen’s production Play it Again, Sam (1968), a role which Keaton landed for being just two inches shorter than Allen (a foreshadowing of her relationships to come). The production gleaned her further roles in Love and Other Strangers (1970), and various appearances in TV shows and advertisements, before breaking into the mainstream in Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather (1972). Keaton, despite being cast for her eccentricity and playing alongside the brooding masculinity of Al Pacino and Marlon Brando, delivers a muted yet powerful performance, cementing the masterpiece in its iconic final shot. Following the success of The Godfather films, Keaton returned to Allen’s Play it Again, Sam in its adaptation of the same name.

“I became famous for being an inarticulate woman”

1977, however, was when everything changed: Annie Hall is a masterwork, a satirical romance so sharp and sincere, it was thought to be autobiographical. Keaton and Allen are one of the great pairings of 1970s cinema, sharing a sharp, neurotic comedic style, entrenched in psychoanalysis and cutting cultural references. In a sense, the character of Annie Hall is Diane Keaton – as per Allen’s idiosyncratic portrait of his then-partner, working the actress’s own quirks and kooks into the screenplay – but Diane Keaton is not Annie Hall. While other actors may become tangled in their typecasting, known only for a career-defining performance, Keaton pushed against the grain and took on darker, more intense roles, such as in the raunchy Looking for Mr Goodbar (1977), Reds (1981), and Shoot the Moon (1982).

In Keaton’s own words, “I became famous for being an inarticulate woman,” particularly against her male counterparts both on and off screen. In spite of this, Keaton’s appeal lies in her creative altruism: where other actors may self-aggrandise, Keaton is self-effacing, putting her art before her image and letting it speak in her stead. The result is an authentic and bygone charm, the absence of which leaves a profound impression on the Hollywood landscape.

Take this instance:

It’s 1978, the 50th Academy Awards, and Diane Keaton has just won Best Actress for Annie Hall. She hops up the steps, looking every bit as ‘kooky’ as the industry paints her. Her acceptance is perhaps the most humble to ever grace the stage. The excitement at being nominated alongside Jane Fonda and Shirley MacLaine exceeds that of the achievement itself: “this is, um, something. Anyway…”

“Diane wakes up in the morning and starts apologising for being alive”

Keaton’s supposed ‘inarticulate’ nature is not a ditsy, air-headedness, but a product of her self-deprecating nature: she would rather talk about anything but herself. As Woody Allen describes it: “Diane wakes up in the morning and starts apologising for being alive.” Interviews with Keaton are marred by delightful segues and tangents, the symptom of a restless creative mind. The outward projection of the Meisner technique (studied by Keaton in New York, 1965) is no doubt a factor in her attitude: “I’m more instinctive than verbal, and more visual”. Keaton exemplifies the plight of beleaguered artists the world over: the art is the communication that need not be explained. The world of celebrity, therefore, was never a good fit for Keaton, being private and self-effacing. Yet, in spite of this, Keaton found a balance between fame and privacy in which she could co-exist before and behind the camera, such as executive producing Gus Van Sant’s Elephant (2003), and directing the ‘Slave and Masters’ episode of Twin Peaks.

In truth, Diane Keaton can’t be described in words. To consign her character to a profile is next-to impossible: we must watch her, as she is, on her own terms. We watch her move, every nervous tick, every ditzy bumbling, and its beautiful resolve. Even better, is to listen to Diane Keaton, be it speaking or singing. Her rendition of ‘Seems Like Old Times’ in Annie Hall is disarming, an interlude that focuses all of our attention on Keaton the actress, rather than Annie the character. It is an arresting moment on a rewatch of Annie Hall since Keaton’s passing: a reminder of what once was.

We may have lost Diane Keaton, but what remains is a veritable collage of performances, passions, and pursuits that make up this once-in-a-generation talent. What we can learn from Diane Keaton is the value of benevolence and sincerity in art and life: the courage to forge your own path and take up space among giants, but not at the expense of authenticity. Watching Diane Keaton laugh at herself or deflect a probing question is delightful: it is refreshing to know less about the private, so as to know more about the art at hand.

News / Cambridge academics sign open letter criticising research funding changes22 February 2026

News / Cambridge academics sign open letter criticising research funding changes22 February 2026 News / University Council rescinds University Centre membership20 February 2026

News / University Council rescinds University Centre membership20 February 2026 News / Supporters protest potential vet school closure22 February 2026

News / Supporters protest potential vet school closure22 February 2026 News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026 Comment / A tongue-in-cheek petition for gowned exams at Cambridge 21 February 2026

Comment / A tongue-in-cheek petition for gowned exams at Cambridge 21 February 2026