AI is all the rage. News channels, social media outlets, and academic content is flooded with debates on its significance. Topics have ranged from AI competing with graphic designers for jobs, a multi-corporate race for superintelligence, and whatever the hell “vibe coding” is.

It is easy for students to think that artificial intelligence is taking over the world, San Franciscan start-up by San Franciscan start-up, and that our future is as uncertain as ever. Us Geography undergraduates spent our first lecture of the academic year being told how we can and can’t use AI for our work, and how to accurately reference it as one might within a bibliography. It is no secret that AI is here to stay, but a question I find increasingly interesting is what else is on the horizon: is it aliens? Unicorns? An army of robocops patrolling King’s Parade? Most likely not. What is likely, however, is the unprecedented rise of quantum machinery.

I would be lying if I said I understood the complexities of quantum computing in its entirety. I am but a humble humanities student, and only know what I can piece together from FT articles, YouTube videos, and conversations with some particularly nerdy STEM friends. In essence, quantum is first and foremost a revolution in computing, and the number of calculations a machine can make in a given timeframe.

If we imagine a classical computer, any one of the two thousand Apple Macs in the Marshall Library will do, then consider its computation existing in straight lines. When attempting to crack an encrypted piece of data, it can only follow different pathways around the wall one at a time. While relatively slow, this is largely why we can trust the firewalls online, as much of our sensitive data on the internet is protected by the Rivest-Shamir-Adleman cryptosystem.

“Do we want the foremost leaps occurring in academic powerhouses such as Cambridge’s Quantum Computing Group, or in mega tech firms like Google?”

Overcoming this algorithm would require a classical computer to perform an entirely infeasible number of calculations, with the RSA-2048 encryption key requiring a timescale on the order of billions to trillions of years, older than the age of the universe. Quantum computers, however, avoid this problem by using quantum bits (qubits) in a state of superposition. These qubits can follow multiple pathways simultaneously, and it has been predicted that an effective fault-tolerant quantum computer could crack the same RSA-2048 key in under a week – though we are far away from realising this theoretical machine. The system of straight lines becomes a giant cloud, and RSA algorithms lose their effectiveness incredibly quickly.

Alas, if only it was as simple as this. Quantum systems, much like our mathmos locked away in the CMS, are highly sensitive to environmental interference. Heat, electronic signals and electromagnetic fields can all potentially destabilise the qubits needed for these rapid calculations. Quantum computers are therefore held in cryogenic chambers to avoid this from happening, an expensive and technically complex feat of engineering. Furthermore, large error corrections and challenges with scalability means the systems are currently unable to push the magnitude of calculations needed to decode RSA, limiting their effectiveness.

Like most up-and-coming technology, quantum is a work in progress. The difference, however, is the significant threat its materialisation poses against online data. An effective and practically viable quantum algorithm could decrypt valuable information such as online banking transactions, medical records, intelligence databases, and Outlook messages (society presidents, beware). With stakeholders such as IBM and Oxford University all investing heavily in quantum technology, it begs the question of who we want in control of this key. Do we want the foremost leaps occurring in academic powerhouses such as Cambridge’s Quantum Computing Group, or in mega tech firms like Google? As an effective quantum algorithm wields unprecedented power, so too will the shareholders that own it, and detailed policy will be needed to ensure this key is used wisely, competitively, and fairly.

“The tendency to direct our energies on AI could be letting this revolution slip away quietly under our feet”

Movement towards when quantum systems are practically (and commercially) viable is already making significant headway, being known colloquially amongst interested parties as “Q-day”. This October, Google claimed its quantum systems performed complex simulations 13,000 times faster than classical supercomputers, and IBM, a leader in this field, hopes to achieve major milestones before 2027. Cambridge is not immune to this revolution either, with former Senior Research Fellow Steve Brierley founding his Quantum Error Correction firm Riverlane in the city due to the UK’s “amazing, industrial strategy that started in 2014”.

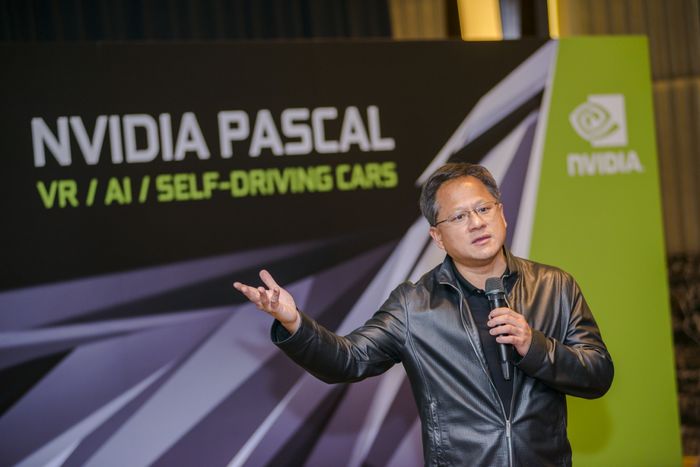

Even Jensen Huang highlighted in the Union that developments were occurring faster than previously thought. By Christmas, new and shinier headlines will dictate the steadily advancing rate of scientific progress here, something to scan for as you browse the FT for your daily dose of application-ready headlines (I’m talking to you, second years).

The point of this article is not that doom and gloom is inevitable, but rather that despite AI occupying the majority of headlines (ironically, including this one), other forces ought to be in the conversation. Q-day, and the surrounding developments in quantum engineering, combines a variety of interesting economic, geopolitical and environmental themes. It is not some half-predicted event in the distant future, but rather an inevitable moment in technological innovation. Instead of getting tunnel vision about OpenAI’s latest LLM’s, Gemini’s free student membership, and whatever Grok is doing nowadays, we ought to start bringing quantum into the fold.

Quantum computing is not merely a revolution in cryptography, but also research and development in life sciences, materials, clean energy and other pivotal areas of science. There is much to be positive about, and I believe that these systems are worthy of our voices and ears, and that the tendency to direct our energies on AI could be letting this revolution slip away quietly under our feet. There is one thing that Cambridge students do better than any other, and that is talk. So let quantum be a part of the conversation, before this quiet revolution becomes unbearably loud.