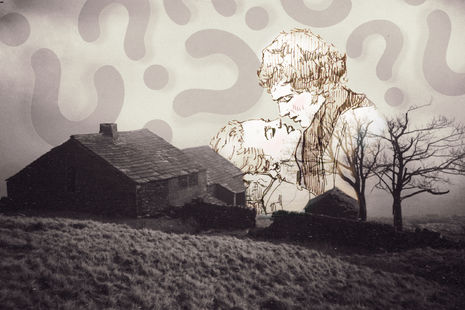

Reimagining the classics in Fennell’s Wuthering Heights

Daniella Adetoye questions the fate of Emerald Fennell’s star-studded Wuthering Heights adaptation

Last month, the teaser trailer for Emerald Fennell’s adaptation of Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights blew up online. While some of this hype was due to hyper-aestheticised shots of Jacob Elordi to a Charlie XCX soundtrack (which genuinely fooled me into thinking I’d accidentally opened a TikTok thirst edit with studio funding), the real source of controversy revolved around the film’s anticipated historical and literary inaccuracies that Fennell’s aesthetic choices seemed to entail. If the trailer is anything to go by, this Wuthering Heights adaptation will be unapologetically built on sex, horror and discomfort, typical of Fennel’s style of spectacle that seems to be the antithesis of Brontë’s gothic restraint and psychological nuance.

Fennell’s filmmaking has always thrived on provocation. From writing on Killing Eve to directing Promising Young Woman and Saltburn, she has cultivated a recognisable style: aesthetic excess, unsettling eroticism, dark humour and morally ambiguous characters. She emphasised her willingness to push audiences into discomfort in a 2023 interview, claiming, “why cut when you’re seeing something […] that feels both horrifying and profoundly real?” Fennell’s commitment to pushing sensory boundaries and leaving audiences uneasy has become a staple of her filmmaking style and artistic identity, which viewers have come to anticipate in any project she undertakes. This expectation, combined with the trailer’s provocative tone, has led audiences to question whether Fennell’s characteristic spectacle and eroticism can truly capture the gothic subtlety of Brontë’s work.

“Wuthering Heights marks Fennell’s first adaptation of pre-existing media”

Wuthering Heights marks Fennell’s first adaptation of pre-existing media, a task that requires balancing a loyalty to the text with her distinct creative style. Brontë’s novel is a gothic story of revenge and passion, told through layered perspectives that create a sense of mystery and emotional restraint. The text is famously “wild” yet largely uninterested in the glossy cinematic glamour that defines Fennell’s work. By contrast, Fennell’s filmmaking is defined by glossy self-awareness and deliberate excess, creating a heightened sense of spectacle. These traits are most clearly seen in the collision between Saltburn’s tongue-in-cheek 2000s pop-soundtrack with the lavish, hyper-stylised dark-academia decadence of Wuthering Heights. The stark mismatch between Brontë’s bleak tone and Fennell’s glossy surplus sparked the early wave of criticism around her stylistic approach.

These initial worries quickly expanded into broader concerns about casting with Margot Robbie playing the younger, brunette Catherine and the racial debate around Jacob Elordi’s portrayal of a character Brontë describes as “dark-skinned” and ethnically ambiguous. To many fans, these choices suggested that fidelity to the text had been disregarded in favour of internet-popular actors who suited the trailer’s polished, internet-ready aesthetic. Following the trailer's release, the term “Saltburnification” circulated across social media, shorthand for the fear that Fennell might transform Brontë’s tragedy into an attention-grabbing spectacle designed to go viral. Similar critiques have resurfaced that she prioritises style over substance and uses shock to replace thematic depth.

“When a text is as structurally strange as Wuthering Heights, strict loyalty to the plot seems almost impossible”

These reactions raise broader questions about what the purpose of adaptation should be. When a text is as iconic and structurally strange as Wuthering Heights, strict loyalty to the plot seems almost impossible. So, there may be some value in the creative liberties Fennell seems to be embracing. Brontë’s novel was scandalous when it appeared in 1847; its intensity, violence and obsessive passion horrified its original readers. For a 21st-century audience desensitised to brutality, perhaps a heightened strangeness is necessary to recapture that shock. Dismissing Fennell outright would be premature, as her preoccupations with class tension and unstable desire align closely with the novel’s darker currents. The casting of Jacob Elordi as another destructive-yet-idealised male figure echoes Heathcliff’s long cultural afterlife as a symbol of violent allure. In this sense, Fennell may be attempting to translate Brontë’s emotional brutality into an aestheticised cinematic language for a new generation.

Ultimately, the success of this adaptation depends on whether Fennell’s erotic, hyper-stylised approach can illuminate, rather than overshadow, the novel’s psychological and emotional complexity. Wuthering Heights is not just a story of passion; it is a study of trauma, social suffocation, generational damage, and the impossibility of love under violence. If Fennell can channel these themes without reducing the narrative to spectacle, her version may genuinely reintroduce Brontë’s wildness to a contemporary audience. If not, it risks becoming another example of her excess in visual style leading to a controversial, but thematically hollow film. Either way, she is taking a modern approach to the tone and mythology of Brontë’s works. The only question now is whether the moors will bend to her vision or simply swallow it whole.

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026 News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026 News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026

News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026 News / CUCA members attend Reform rally in London20 February 2026

News / CUCA members attend Reform rally in London20 February 2026 News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026

News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026