Dissent: a brief history of student protests and demonstrations

Emily Chan delves into the violent history of Cambridge activism ahead of the NUS London demonstrations, questioning whether the passage of forty years has altered the power of the picket

The events that took place in Paris during May 1968 became catalysts for other protests in cities such as London, Prague, Berlin, Chicago and Mexico City. 1968 became a landmark year for student activism across the globe.

In Paris, the threat to Charles de Gaulle and his conservative government was very real. Images of violent clashes with riot police, burning cars and barricades were broadcast worldwide. The protests stemmed from discontent about an inadequate university system, where student numbers had doubled from 250,000 to over 500, 000 in five years. However, the demonstrations also reflected more general concerns about the nature of the society in which they were living. The students were later joined by workers: around 10 million participated in a general strike across France, bringing the country to a halt for almost two weeks.

Although mass student protests had been taking place prior to May 1968, as in Berlin, the demonstrations in Paris brought newfound energy to political activism in campuses across Europe and America.

However, Dr Philip Morgan, a history student at Queens’ from 1967-70, recalls that in Cambridge there was less activity than other places: “I don’t have the impression that protest was a regular aspect of student life, certainly not at Cambridge anyway; students elsewhere – the LSE, continental Europe – always seemed to be more active and militant.”

Nevertheless, in November 1968 there was a large demonstration outside the Cambridge Union against the visiting speaker Enoch Powell, who had been sacked by Edward Heath from his position as shadow defence secretary following his ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech. Speaking in Birmingham, he had suggested that Commonwealth immigration policy was “mad, literally mad”.

The November protest was a fairly tame affair, as Varsity reported: “Enoch Powell’s visit to the Union last Sunday passed off without an incident. The threat of violence was never put to the test, as demonstrators outside the Union waited for hour after hour for a Powell who refused to appear. In fact, he had been craftily smuggled in at least two hours before the demonstration was due to start, and he left two hours after it should have ended.”

On the same day, Cambridge students joined 50,000 people on a march in London, which the writer of the article describes as “a very depressing experience”, criticising “meaningless slogans” such as “Disembowell [sic] Enoch Powell” and branding fellow protestors as “second-rate intellectuals and grudge merchants”.

Although there were not any other major demonstrations in Cambridge in 1968, the political climate was clearly heating up in the latter part of the decade. There was, as a ‘60s retrospective in Varsity from June 1969 noted, the “development of a militant left” which could “be traced from the growing dissatisfaction with the Union through the split of the Labour Club into Soc. Soc. [Socialist Society] and the DLC [Democratic Labour Club] to the setting up of the 1/- Paper”. The Shilling Paper – a left-wing, anti-establishment alternative to Varsity – was founded in the same year as the Paris protests.

Rod Caird, an Oriental languages student at Queens’ from 1967 -70, was involved in the production of the Shilling Paper, which “brought together people from very disparate groups on the liberal – and not so liberal – left.” “The left,” he says, “was active, busy and noisy; students had found an independent voice on all kinds of subjects and were unafraid to use it. It was a time of personal and political radicalism which affected all aspects of life, from the petty restrictions of college life through to global issues of peace and anti-colonialism.”

The Vietnam War was a focus for demonstrators in the late 1960s, as was the apartheid regime in South Africa. In February 1969, 200 campaigners from the Cambridge University South Africa Committee (CUSAC) marched on Trinity College in objection to the Dryden Society’s planned tour of the country. The crowd was addressed by the expelled Bishop of Johannesburg, Ambrose Reeves, and the South African poet Dennis Brutus, who said: “Players that come on the terms of apartheid, declare to the world that apartheid is okay, and reassure those South Africans with twinges of conscience.” The protest was ultimately unsuccessful: the tour went ahead that summer with the Dryden Society performing to segregated audiences.

Anger at the military dictatorship in Greece came to a fore during Greek Week in 1970, which was organised by the country’s tourist board and supported by travel agents in Cambridge to promote tourism. On Tuesday 10th May, students occupied Abbott’s Travel Agency in Sidney Street, and burnt posters on the pavement outside, as was reported in this paper by a 20-year-old Jeremy Paxman. A series of protests culminated on Friday 13th May at the Garden House Hotel, where a dinner was being held to celebrate the conclusion of Greek Week. Around 400 students picketed the hotel, but the peaceful protest descended into violence as the police attempted to break up the demonstrators.

“When we heard of plans by Cambridge travel agents and the city to organise a special week promoting tourism in Greece, it could hardly have been a more blatant provocation,” explains Caird, who was 21 at the time. “Greece…was ruled by a military junta with an appalling record on human rights and deserved to be isolated and shunned, rather than visited and supported.”

“The demonstration, frankly, did get a bit out of hand and a number of us – including me – were arrested, eventually being charged for a variety of alleged offences including riotous assembly, possession of offensive weapons. To the authorities, this was a heaven-sent opportunity to make an example of long-haired, trouble-making leftie students who should have known better. It was an election year and we were a very convenient target.” In July, six students were jailed, with Caird receiving an 18-month sentence.

Asked if he regrets his part in the Garden House Riot, he says: “I genuinely don’t think I would have done anything differently. Hindsight is a wonderful thing and it was stupid to get myself arrested, but I would not hesitate to go to that demonstration again.” Caird expressed similar sentiments in a Varsity interview in November 1971, having spent 12 months at Wormwoods Scrubs and Coldingley Prison: “The only moment that really hurts is the clamping on of the handcuffs”.

Although international issues remained in the consciousness of Cambridge students – including student demonstrations at Harvard in the USA – protests after Greek Week seemed to be more focused on the immediate concerns of university life. Demands for reforms to the disciplinary system at Cambridge led to a picket of over 800 students outside the Senate House in October 1970, which attracted heavy police presence. Strained negotiations were taking place between the Cambridge Student Union (CSU) and the vice-chancellor, Professor Owen Chadwick.

In February 1972, there was an Old Schools sit-in expressing anger at the University’s hostile response to proposed examination reforms, which was followed by more sit-ins at Lady Mitchell Hall and at the Faculty of Economics in February 1973, after the rejection of examination reforms to the economics tripos. The 1973 sit-ins ended with a march of 1,500 students to Senate House, where they handed in a petition with more than 3,000 signatures calling for the start of negotiations for reform in all faculties. Proposals included the abolition of Part I and prelim classifications, making Part I more interdisciplinary, and replacing certain examinations with dissertations or portfolios.

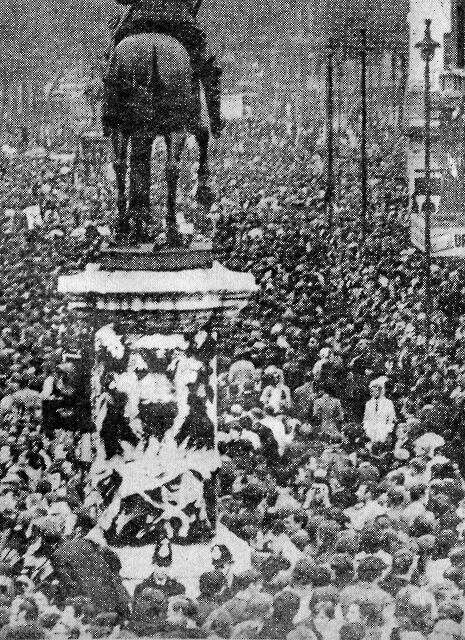

At the beginning of 1972 there were also protests against the government’s plans to reform student unions. In January, around 600 took part in a march, which was obstructed at Magdalene Bridge by a group of about 50 right-wing students. Despite the ambush, the protestors went on to deliver an anti-government petition to Shire Hall. In the same month, the biggest student demonstration up to that point took place in London, in a rally led by the (NUS). In total 35,000 students went to the capital, including a Cambridge contingent of 700. The pressure put on the government prevented Margaret Thatcher, who was then Education Secretary, from carrying out the proposed reforms.

Fast-forward to the present day, and plans for an NUS demonstration in London on 21st November are in full swing.

The apparent shift in focus at the beginning of the 1970s within the student community to more domestic issues is reflected in the concerns of today: student fees and government cuts. Dr Morgan suggests that although the essence of student protest has not changed much since the late 60s and early 70s, there is now an even greater need for action: “Today’s students have much more to protest about, from student fees to finance capitalism.” He also notes the advantage of using social media: “The forms of protest are much more sophisticated and effective, with extensive use of virtual media to organise and mobilise, and guerrilla-type, almost carnival-like staging of events, again primarily to shock, inform, target and mobilise.”

However, as in the ‘60s and ‘70s, there are debates taking place about the effectiveness of student protest. Only last week, the Cambridge University Council defended the procedures of the Court of Discipline, following a review into the case of Owen Holland, who was initially rusticated for seven terms for his part in the protest at a talk given by the Universities Minister, David Willetts, in November 2011. Holland’s suspension was reduced from seven terms to one term by the appeal court.

Caird thinks that the punishment was unjustified: “The action against Owen Holland is disgraceful. He read out a poem; I don’t believe the University is entitled to discipline people for an offence which may have embarrassed them but certainly caused no harm or mischief. After I was convicted and sentenced an attempt was made, with the support of the then President of Queens’, to withhold my degree on the grounds that I had “brought the University into disrepute.” Fortunately we had enough support among senior staff to overturn that proposal at the Senate and my degree certificate duly turned up in the mail in Wormwood Scrubs.”

There was also controversy after the protest against tuition fees in December 2010, when Charlie Gilmour, a history student at Girton, was sentenced to 16 months in prison after admitting violent disorder. Concerns have been raised by NUS President Liam Burns about the extent to which incidents such as these and the outbreak of violence at the NUS protests two years ago detract attention from the key messages. Hannah Kaner, a second-year English student at Pembroke, believes that unity is vital and fears that violence would undermine the credibility of the protest: “I think protesting is the only way people can demonstrate a united voice and make the rest of the country aware of it. The NUS protest this month tells the government that people aren’t just numbers on a list. However, violence makes the message one of desperation, not of unity.”

CUSU will be sending coaches to the NUS demonstration. Speaking about the importance of student activism, CUSU President Rosalyn Old says: “Student protest was not new in 2010 – but what we are seeing now is a wholehearted shift in the way that education is perceived in this country. Some said that the protests two years ago did not work – £9000 fees still happened. But protesting is not just about instant results. It’s about making the student voice heard, raising awareness and engaging people in the issues. And previous protests have certainly done that.

“The NUS Demo 2012 on the 21st November is important, but it does not end on the 22nd – it has to be part of a longer-term vision, and CUSU already has plans in place for follow-up events and campaigns. Most of all, the art of protest and campaigning is about empowering people. It’s about having our voices heard and fighting for the positive changes that we believe in.”

News / Colleges charge different rents for the same Castle Street accommodation2 March 2026

News / Colleges charge different rents for the same Castle Street accommodation2 March 2026 News / News in Brief: waterworks, wine woes, and workplace wins 1 March 2026

News / News in Brief: waterworks, wine woes, and workplace wins 1 March 2026 News / Climate activists protest for ‘ethical careers policy’1 March 2026

News / Climate activists protest for ‘ethical careers policy’1 March 2026 News / Angela Merkel among Cambridge honorary degree nominees27 February 2026

News / Angela Merkel among Cambridge honorary degree nominees27 February 2026 News / Private school teacher who lied about Cambridge degree barred from teaching27 February 2026

News / Private school teacher who lied about Cambridge degree barred from teaching27 February 2026