Vintage Varsity: the queer scene

Resident archivist Iris Mamier explores the evolution of the queer scene in Varsity, and its collision with Cambridge’s upper class gay tradition

Cambridge has a strong queer community and history, and is frequently listed (by Cambridge students anyway) as one of the best places to be gay as a student. Yet vintage depictions of the ‘scene’ by Varsity authors both gay and straight conceal a disdain which could hardly be described as thinly veiled. Past editions of Varsity reveal a tension between Cambridge’s upper class homosexual tradition, with its emphasis on maintaining morality through discretion, and the emerging queer ‘scene’ in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. I searched the Varsity archives to further explore how queer life at Cambridge has been represented as a collision of two competing ideas of what it means to be gay, and as a class struggle between town and gown.

“Homosexuality is only attractive when it encapsulates loneliness, isolation, and long, cold holidays in autumnal Venice”

The author of ‘From Our Cambridge Correspondent’, Mark Weatherall, dedicates a full two pages of his book to gay life at Cambridge. “Homosexuality hardly appears in Varsity before the 1970s,” he states, with the exception of an odd two week period in the aftermath of the 1958 Wolfenden report. After the Wolfenden committee advocated for the decriminalisation of homosexuality, Varsity’s coverage was intensely curious about homosexuality in Cambridge – that is until the proctor’s office raised objections. It calculated that there ought to be at least 320 homosexual male students at the University, and sought to deduce their character. Homosexuals were “not as rampant” as just after the war, claimed the Senior Tutor of Kings, while the Senior Tutor of Trinity Hall differentiated between two types of homosexual: the “queer gang” who were purposefully subversive and promiscuous, and the other kind whose homosexuality was connected with “extreme depression”.

Queerness at Cambridge traditionally maintained a veneer of upper-class respectability. Even going into the 80s, Varsity declared that, “The public school and academic ethos is still prevalent in the university: it is believed that these help swell the numbers [of homosexuals]”. The upper class homosexual put the “English” into “English vice”. He was, very importantly, male, and was respectable despite his proclivities.

The emergence of the queer scene, and its piercing of the Cambridge bubble, therefore, created a kind of moral outrage. Cambridge’s vibrant ‘LesBiGay’ community (as it was described in early 2000s editions) should have been a source of pride, one author stated in 2002, but the participation of individuals in a scene which emphasises party and sex is detrimental to the cause and “ruins people’s lives”. Straight and gay authors alike called for a return to the ‘upper class sensibilities’ which had once rendered Cambridge’s gay tradition honourable. “Homosexuality,” according to a 2003 comment article, “is only attractive when it encapsulates loneliness, isolation, and long, cold holidays in autumnal Venice”. Its “mistaken” surrender to the “lower classes,” to the gaudy, to the counter-cultural, and to the revolutionary, renders it ‘ugly’.

“The dichotomy of the ‘queer gang’ gay versus the upper-class dandy was and is simply a matter of class prejudice”

In Michaelmas term 1982, Varsity reported that a ‘New Voice for Gays’ had arrived on the scene – a gay society which was distinctly “non-scene”. The Alternative Homosexual Group (or AHG) was launched by Peter Robertson as an alternative to “the commercial club scene of the 451 CLUB and the militancy of Gay Cambridge”. Robertson deplored the “scene homosexuals,” and “mindless promiscuity” of gay sub-culture, and with AHG sought to bring back the image of the intellectual homosexual through a culture of debate. Where GaySoc had complained that few homosexuals were willing to celebrate “gay pride” at the cost of social acceptance, Robertson put the burden on gay students to make themselves more palatable. “Homosexuals just don’t project themselves,” he said, “and if they want equality they’d better stop their juvenile abandonment”.

The dichotomy of the ‘queer gang’ gay versus the upper-class dandy was and is simply a matter of class prejudice. The scene constituted a threat to class hierarchy, and in rejecting it, gay students hoped successful class performance would render their sexuality irrelevant. If homosexuality was only made acceptable by its upper class sensibilities, then the way in which students and ‘townies’ socialised together in LGBTQ+ spaces actively blurred the Town vs Gown divide. A Varsity investigation post-Wolfendon found that homosexual Cambridge students were more likely to go to homosexual parties given by townspeople.

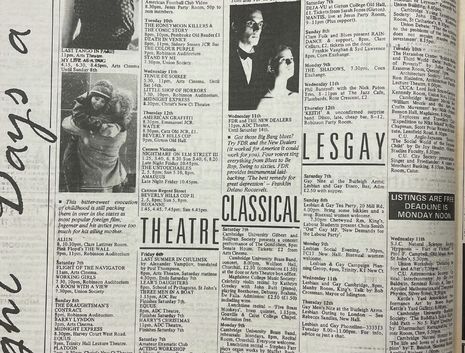

Vintage Varsity: Don't just hope - get the facts

The narrative of homosexuality’s ‘surrender’ to the scene was one which arguably served to legitimise criticisms of homosexuality on a moral basis after its decriminalisation. No such binary truly existed. Beginning in the 80s, and appearing last in February 1988, the ‘LesGay’ column on Varsity’s events page advertised a wide range of queer events: from discos to protests and everything in between. In November 1987, for example, Varsity advertised the following events taking place that week alone: a disco, a Lesbian & Gay Tea Party, a Lesbian social evening, a Gay men’s night, and a Lesbian and Gay Campaign Planning Group. The Lesbian & Gay Tea Party implored attendees to “Bring some bikkies and a mug,” before adding “Bisexual women welcome”. Personally, I think we should bring that back.

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026 News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026 News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026

News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026 News / CUCA members attend Reform rally in London20 February 2026

News / CUCA members attend Reform rally in London20 February 2026 News / Gov grants £36m to Cambridge supercomputer17 February 2026

News / Gov grants £36m to Cambridge supercomputer17 February 2026