The unexpected joy of flat dinner

Columnist Hannah Gillott elucidates the power she found in eating dinner with her flat, both for forging strong, new friendships and addressing her relationship with food

There’s a moment, making new friends, where the first group chat gets made.

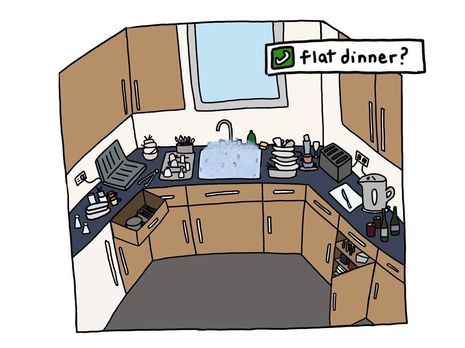

Eventually it’s rendered useless - its members are representative of a freshers preserved only in matriculation photos and memories of a Lola’s night you’d rather forget. But for its time, that first group chat is an anchor, which says that you’re in this Cambridge thing for the long haul, and maybe - if you can imagine it - you might actually settle into a life here. It’s a palette which will one day be marked by inside jokes you haven’t laughed at even once yet, let alone rinsed dry. From halting club night plans to pub trip bookings, then reunions you will desperately need in the unimaginable 5 weeks apart at Christmas, you inexplicably find yourself at holidays, with people whose initials marked doors you were too nervous to even knock on, but who have somehow become your midnight calls. For me, this first piece of the puzzle - the corner you tentatively place down first, wondering if it could be right - was the flat dinner group chat, whose messages, taken from friends who happily volunteered to be exploited for this article, went something like:

flat dinner in 15 come to JCR

i think we were thinking easy and minimal washing

flat dinner then awful christmas film sounds good :)

see you for flat dinner and harry potter when you’re back!!

flat dinner tonight before carols?

I’ll probably go to sainsburys anyway so can pick something up for flat dinner

can we do flat dinner today I’m not convinced by the hall menu :(

flat dinner around 630 halloumi, veg and rice

Flat dinner served as a real and metonymic anchor in being both a daily gathering and our group chat name. More than just reassuring me that I had a place in this new life I was forging,though, it transformed my relationship with food. It eased the transition from days punctuated by family meals to one entirely unstructured - when waking up at midday and staying out till 3am didn’t only have awful repercussions for my lecture attendance, but provoked an ever present, low level anxiety over what I was eating. Was hungover avocado on toast (always stale - my flatmate and I hadn’t yet discovered communal bread, despite buying exactly the same loaf) now my lunch? Were chicken nuggets from the Van of Life a breakfast substitute or a second dinner? And what the fuck did drinking this much mean in my unconscious, unwanted, but seemingly unavoidable, recalculations?

“I danced as we washed up, unable to see for my overpowering joy and the alcoholic haze that evening was melting into night”

Yet eating a flat dinner meant that at around 7 each night I leant into the ease of a community meal. I stood in the gyp, propped open by whoever acted as doorstop that evening, on the rolling chair magicked out of nowhere, while conversations ricocheted off the fresh painted walls to those of us who spilled out into the corridor, the physical manifestation of a kitchen (a term generously employed) overflowing with love and bubbling over with laughter. I watched as friends were more creative with our George Foremans than I could ever be with words, and shared in amazement as we moved from halloumi to salmon to stuffed peppers, fuelled by the stale tortilla chips left on the countertop, spite at being denied a hob, and Aldi wine we had stored, propped in the baskets of our bikes the week before. I danced as we washed up, unable to see for my overpowering joy and the alcoholic haze that evening was melting into night. And somewhere amongst this increasingly complex, lengthy and numerous ritual, I sat and ate. And I didn’t notice how much, or when, or who was eating more or less, or whether it was too much or too little or too similar to the night before, or what came next or before it. I ate. And that was all. And it was nothing and because of that it was everything.

A term later, reflecting on the unwitting progress I made and discussing the shocking significance of a group meal with my college wife, I realised how much community had altered my conception of food. Once scared to even sample a dessert, I could now savour a four course meal at formal, surrounded by people I loved and supported by an uncomfortable wooden chair and a Cambridge tradition, both seeming to date back centuries. A starter, once unthinkable, was welcome when it was half a roll of challah, split with a friend over friday night dinner and dipped into chicken soup, the warmth it lacked that week replaced by the heat of tens of people sharing a sense of community and a smile across the rickety table.

“At flat dinner, food was not calculated, nor was it glorified or demonised”

Throughout my eating disorder recovery, such community practises have been a goal. I longed to joyously devour a Christmas dinner, unaffected by the scattered Quality Street wrappers, who had yearly taunted me with their nauseating glow. Yet I had never imagined that what I had aimed for would in fact be my path to recovery. For those of us who have at some point found food itself reduced to numbers, partaking in a shared meal steeped in tradition - be that on Christmas, Hannukah, or Ramadan - although terrifying, is a powerful reminder of what food has been and always will be: a point of connection. At flat dinner, food was not calculated, nor was it glorified or demonised. It was half a pack of suspiciously slimy mushrooms from one fridge and the leftover chicken from another. It was the Lurpak from the big spender of the group and the buttersoft from the rest of us. It was mismatched crockery, mine blue, someone else’s chipped and none ever returned, the identical cutlery from our parallel IKEA shops and the rare bendable ones which we had warped into loops over the course of term, and mugs instead of wine glasses.

It was free, and after a while, so too was I.

And as I run to Flat B’s kitchen at 7:30 tomorrow night, having raided my fridge for wine and a red pepper, I’m reminded of just how lucky I am to have been given the chance to rediscover this.

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026 News / University Council rescinds University Centre membership20 February 2026

News / University Council rescinds University Centre membership20 February 2026 News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026 News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026

News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026 News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026

News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026