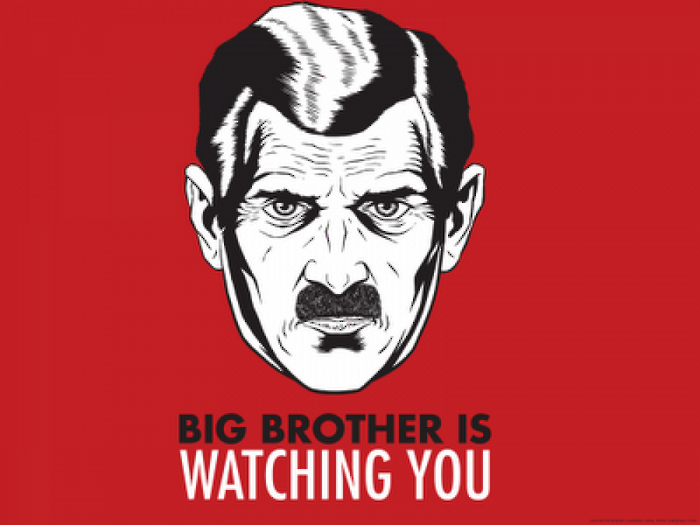

Google or the government, who is the real Big Brother?

“Google and Facebook are unelected, unaccountable and wield more influence than many a small nation-state”

Since the Edward Snowden revelations of 2013, we’ve been familiar with the trope of the ‘snooping’ government watching our every move like Big Brother come true. It’s splashed all over the papers, usually presented as a choice between individual privacy and national security – and the stakes have been raised with recent anti-terrorism legislation. Should we be afraid? A few weeks ago I would have said yes – but a polarising panel discussion at this year’s Wilberforce Society conference made me change my mind.

It’s undoubtedly true that the government is increasing its capacity to collect and analyse our data. The Investigatory Powers Act of 2016 enabled the British government to indiscriminately monitor phone calls, emails and other communications, in addition to location data – something Silkie Carlo, the Director of Big Brother Watch, labelled the most intense surveillance regime in any democracy in history. Security cameras equipped with facial recognition have also been rolled out for large-scale events, such as at stadiums hosting Six Nations games and the Notting Hill carnival. These check the faces of passers-by against a national criminal database – without them even knowing. Our government can now collect an overwhelming quantity of data with great ease.

“We need a legal framework to adapt to the new challenges the world is starting to face”

There are plenty of reasons to be hesitant. History is littered with examples of states pushing through reforms that sacrifice individual liberties during times of crisis – from Abraham Lincoln in the American Civil War to Hitler after the 1933 Reichstag fire. Scaremongering about terrorism in the UK could be construed as an excuse for the UK government to push through intrusive policies. Given Trump’s disregard for a wide array of human rights, concerns about democratic slippage are the minds of human rights campaigners all over the Western world.

However, Dr Tamara Makarenko, an academic and freelance intelligence consultant on the panel, dismisses these concerns. She maintains that within democracies, having an independent judiciary means that legislative powers can always be kept in check. We can see this in action with the Investigatory Powers Act, which was legally challenged by Liberty, a UK-based human rights group of which Carlo was the Senior Advocacy Officer. The Act was also ruled illegal by the European Court of Justice, because it allowed the “general and indiscriminate retention” of data without oversight from an independent body.

“Technology companies also have significant influence over political governance”

Dr. Makarenko maintains that as long as we make sure surveillance measures are proportional to the security risks the country faces, and that the system is open to legal challenge from its citizens, that we have nothing to worry about. Drawing upon John Locke, she argues that “there’s nothing wrong with giving up liberty for security, as long as the centres of control are themselves controlled.” We need a legal framework to adapt to the new challenges the world is starting to face, including measures for determining necessity, independent oversight and ensuring proportionality with security measures. As Carlo emphasises, to avoid this era of technological change being a turning point for human rights, we need to make the most of the domestic courts we are fortunate enough to have.

On the other hand, tech giants like Google and Facebook are unelected, unaccountable and wield more influence than many a small nation-state. Central to their business model is the collection of all kinds of data – be it from your profile, your friends, your clicks – and selling it to private companies for ‘targeted’ advertising. Google has been fined millions on several occasions in both the US and the UK for collecting data without people’s permission, and Facebook is facing charges across Europe for its data protection rules. Nigel Inkster describes Facebook and Google as “insidious” and “opaque” – and coming from MI6’s former Director of Operations, that’s pretty bold. He estimates that GCHQ is capable of processing only 3% of internet usage (he and Makarenko agree that this is small compared to the capabilities of many of the UK’s state and non-state cybersecurity threats). On the other hand, tech giants have access to, and the potential to process, the entirety of people’s personal data – and, of course, a profit motive.

“The political clout of tech giants is starting to be recognised”

Technology companies also have significant influence over political governance, which Inkster suggests could drive Western society towards authoritarianism in the long run. ‘Echo chambers’ on social media can be blamed for increasing political polarisation and even radicalisation. Given that social media sites, or even search engines, don’t come with a fact-check function, the spread of ‘fake news’ and fake profiles run by bots have become increasingly pervasive issues. As people retreat into their ideological bunkers on social media, issues are debated in a less open way: so if you’re not part of the community being fed fake news, you’re unlikely to know about it. Is this the real threat to democracy? The author John Lanchester noted another chilling side to the ability of tech giants to tailor information to specific people:

“Particular segments of voters too can be targeted with complete precision. One instance from 2016 was an anti-Clinton ad repeating a notorious speech she made in 1996 on the subject of ‘super-predators’. The ad was sent to African-American voters in areas where the Republicans were trying, successfully as it turned out, to suppress the Democrat vote. Nobody else saw the ads.”

The political clout of tech giants is starting to be recognised. Earlier this month, Amber Rudd announced the unveiling of a tool that can accurately detect and block jihadist content online, and told the BBC that it was possible technology companies could be forced to use it by law. But at the moment it seems policymakers are playing catch-up to the rapid development of technology. As Makarenko points out, there are significant issues with jurisdiction when it comes to transnational companies, and the legal system needs to adapt to this if it ever hopes to ‘clip the wings’ of tech giants.

While the media continues to sensationalise the Big Brother state, Inkster suggests that we are “at risk of being a distraction from the real issues”. While unregulated, Silicon Valley poses a greater risk to democratic civil society than state surveillance. This panel discussion showed me that tech giants are the real Big Brother, and they need urgent attention – #wakeupsheeple.

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026 Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026

Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026 News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026

News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026 News / Law don launches divestment petition12 March 2026

News / Law don launches divestment petition12 March 2026 Comment / ‘Don’t worry, I barely revised’: the effort behind performative effortlessness11 March 2026

Comment / ‘Don’t worry, I barely revised’: the effort behind performative effortlessness11 March 2026