Should we stop reviewing student theatre?

Leon Rake questions whether reviews are a valuable exercise in critical thinking or an unnecessary strain on peer relationships

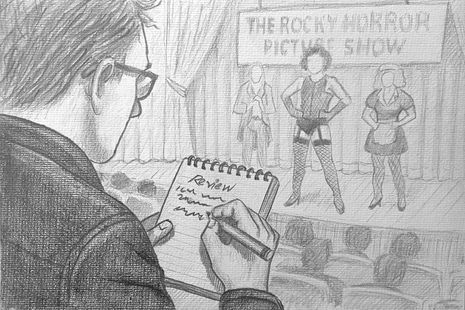

“You were brilliant.” It’s the line we all reach for in the foyer, after every show. Whether the performance was transcendent or teeth-grindingly tedious, it slips out with the same mix of post-show adrenaline and social obligation. Cambridge is small, student theatre smaller still, and no one wants to be the person who punctures the bubble. But what happens when we do? When the lights go up, the review is published, and the praise is not unqualified?

Student theatre reviewing exists in a peculiar in-between. It’s neither professional nor private. Sometimes, it is public writing about deeply personal work, often produced by someone who shares a staircase, a seminar, or a glass of wine with their critic. Reviewers are students, not salaried professionals. Actors and directors are peers, not paid practitioners. And yet the expectation lingers that reviews should read with the polish, rigour, and distance of professional criticism. Is that fair? Is it even possible?

“The intimacy of the student community makes critical honesty feel, at times, like social betrayal”

One argument goes like this: student theatre is learning. Just as we expect to receive feedback on essays or supervision work, we should be able to handle criticism of our creative projects. Reviews provide not only a public record but also a mirror that is sometimes generous, sometimes harsh, but always valuable. They push student theatre to reflect, refine, and reach further. Besides, isn’t art meant to be seen, questioned, challenged?

Yet there’s a difference between receiving critical feedback from a supervisor and reading a semi-anonymous column that describes your emotional vulnerability as “overacted” or your directorial vision as “confused”. The review is not written in a rehearsal room but in the pages of a newspaper. And unlike your supervisor, your reviewer might be in your next audition or in the same pub as you staring into their cider as you walk past. The intimacy of the student community makes critical honesty feel, at times, like social betrayal.

There’s also the matter of tone. Too often, student reviewers fall into a trap: the urge to sound like ‘real’ critics. What results is prose that performs cleverness at the expense of care. A mediocre show becomes an excuse for rhetorical flourish. A well-meaning actor becomes a punchline. And for what? An extra paragraph of flair, a moment of attention, a line to add to your writing portfolio?

“You audition, you rehearse, you perform — and someone writes something you can’t control”

But there is a counterpoint worth considering: not all bad reviews are bad faith. Some are thoughtful, constructive, and brave. Some articulate what an audience was thinking but didn’t know how to say. And, crucially, some plays are bad and deserve to be named as such. There’s a certain tyranny in uncritical praise. When every show is “moving,” “bold,” or “beautifully acted,” language loses meaning, and student theatre becomes an echo chamber of polite applause.

Still, we might ask: is reviewing the best way to have these conversations? Could we imagine alternatives, roundtables or post-show dialogues, that allow space for nuance rather than judgement? Could criticism become more collaborative and less combative? And if not, then perhaps we must simply accept that reviews, as they currently exist, are part of the game. You audition, you rehearse, you perform – and someone writes something you can’t control.

“A review should not always be a verdict”

It’s tempting to idealise student theatre as a purely experimental space, free from the pressures of reputation and recognition. But that would be dishonest. Ambition is everywhere in Cambridge. Many people act or direct because they love it. Others do it to pad out a CV, impress a Footlights panel, or inch closer to the West End. For better or worse, student theatre is a performance of self as much as a performance for others. And reviews shape that self-image.

So, should we stop reviewing student theatre? Not necessarily. But we should rethink how we do it. Reviews should be written with the same courage it takes to walk onto a stage: clear-eyed, self-aware, and compassionate. They should acknowledge the stakes without flinching from the truth. And those on the receiving end should be allowed to disagree, to laugh, to cry, to move on.

Because in the end, a student production is not just a product to be rated, but a process: of collaboration, chaos, and occasionally, something close to brilliance. A review should not always be a verdict. At best, it’s a conversation starter. At worst, it’s a missed opportunity to really listen. And if you’re going to write one, ask yourself first: are you watching to judge, or watching to understand? Because the difference shows.

News / Right-wing billionaire Peter Thiel gives ‘antichrist’ lecture in Cambridge6 February 2026

News / Right-wing billionaire Peter Thiel gives ‘antichrist’ lecture in Cambridge6 February 2026 News / Cambridge students uncover possible execution pit9 February 2026

News / Cambridge students uncover possible execution pit9 February 2026 News / Man pleads guility to arson at Catz8 February 2026

News / Man pleads guility to arson at Catz8 February 2026 News / Epstein contacted Cambridge academics about research funding6 February 2026

News / Epstein contacted Cambridge academics about research funding6 February 2026 News / John’s duped into £10m overspend6 February 2026

News / John’s duped into £10m overspend6 February 2026