She sees you when you’re sleeping

Recent terrorist atrocities have reignited the debate surrounding government internet surveillance and whether it impinges on our human rights. Sam Brown asks if ‘snooping’ is ever justified.

“Any sound that Winston made, above the level of a very low whisper, would be picked up... There was of course no way of knowing whether you were being watched at any given moment. How often, or on what system, the Thought Police plugged in on any individual wire was guesswork.”

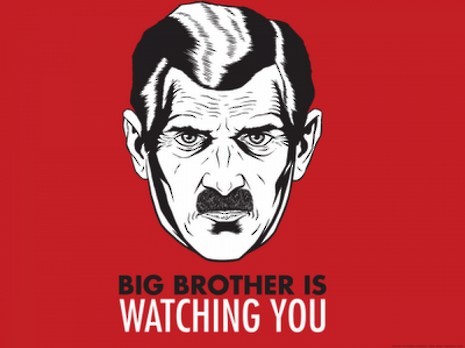

George Orwell’s 1984. Hyperbolic in its outlook, fantastical in its imagery. Yet, crucially pertinent to 2017 and a world in which government surveillance has become a central factor in the fight against terrorist threats. It was only the other week that Theresa May proclaimed that “we need to ensure our police, security, and intelligence agencies have the powers they need [to counter] changing, evolving, and ever more complex threats.” Implied within such a statement is a desire to counter terrorism through further monitoring of internet activity and other forms of cyber data. In Mrs May’s words, the fight against extremism is moving from the “battlefield to the internet”.

Of course, Theresa May has a history of involvement in the issue of surveillance for the sake of security. The Investigatory Powers Act of 2016 was her brainchild. As any lawyer will tell you, this bill is a masterpiece in legislative cunning, purporting to neatly draw together the previously divergent strands of surveillance law while quietly expanding the powers of the government in subtle sub-clauses. The section on “equipment interference” is particularly Machiavellian, effectively authorising mass government hacking under an unassuming and deliberately subdued title.

In short, “equipment interference” allows the Government Communications Headquarters and others to provide any electronics or intelligence company with a warrant to hack their devices, from mobile phones and cameras to computers. The grounds for doing so include national security, preventing or detecting serious crime, and detecting threats “to the economic wellbeing of the UK”. In turn, the company involved will be prosecuted if they tell anyone about this warrant – Apple or Google will never inform you if your device has been hacked by the government, for obvious security reasons. The range of avenues for spying on the population were hugely expanded by this bill. It is no exaggeration to see the development as licensing near ‘police state’ surveillance activities.

“The government’s strategy thus amounts to little more than ‘legalised hacking’.”

Although it caused outrage upon its creation, the bill was largely accepted and forgotten until very recent events threw it into the limelight once again. The horrific attacks in London and Manchester provided a new pretext for an expansion of the surveillance powers that the Investigatory Powers Act already promulgated. But does the answer really lie in simply expanding the surveillance state? A level of surveillance can always be justified in the name of our security, but counter-terrorism should be wider-ranging in its methods, not simply reliant on snooping, however useful this is when used in conjunction with other strategies. The huge cuts in police numbers should be reversed to allow for effective ‘on the ground’ security, as well as better police engagement with certain communities in which extremist ideologies can flourish. Instead of a varied strategy against extremism, however, the government has focused on mass surveillance, not providing enough funding for anti-radicalisation programmes such as ‘Prevent’. The government’s strategy thus amounts to little more than ‘legalised hacking’, an approach that does not get to the root of extremism.

Warrants for such ‘legalised hacking’ clearly antagonise internet-based companies and complicate the relationship between the government and the cyber-community. Liberal Democrat leader Tim Farron has spoken openly about May’s proposals for increased surveillance and offers a less belligerent counter-terrorism proposal. Writing in The Guardian, Farron argues that: “Instead of posturing, politicians need to work with technology companies like Facebook, Twitter and WhatsApp…to develop solutions that work to keep people safe.” Farron is correct. Cooperation, as opposed to exploitation, is key to a successful relationship between government and social media outlets.

Farron, furthermore, mirrors Orwell in his condemnation of mass surveillance, proposing: “If we turn the internet into a tool for censorship and surveillance, the terrorists will have won.” It is therefore true that the steps that the government now take to ‘protect’ our liberties against the spectre of terrorism and online terrorist ideology will come to redefine our internet liberties for decades to come. We are witnessing the development of a new relationship between state and citizen, with spying no longer being the individual-based activity of John le Carré novels, but rather, a brave new world of ever more pervasive mass monitoring.

“Although GCHQ are not the Thought Police (and Theresa May is not yet Big Brother), proper regulation and control over surveillance activities is needed to ensure that we never remotely approach that authoritarian model.”

The advance of household technology arguably facilitates this fundamental change in state-sponsored surveillance. It is now the case that nearly every electrical item in your house has some sort of internet connection, and these connections can be manipulated and monitored by government agencies. I recently spoke to a source, who wished to remain anonymous, with links to GCHQ who said that “intelligence officers can now monitor and remotely alter the heat settings on your household boiler, if they ever wanted to. Any appliance with an internet link can be manipulated.” This potential for intrusion into our lives goes unrecognised and yet is so pervasive that most aspects of human life are now ‘hackable’.

For instance, a recent programme by Vice showed how an ex-NSA intelligence officer was able to ‘hack’ a moving car, gaining control of the brakes, the steering, and the engine function. It is a scary and very real prospect that independent hackers, not affiliated with the government, could use this information and their hacking skills to manipulate vehicles or planes, and cause mass damage. This was explored in depth in the Netflix Black Mirror series: in one particularly dark and chilling episode an anonymous hacker gains access to a boy’s laptop camera and videos explicit material, to be later used as blackmail. The show’s creator Charlie Brooker was ahead of his time in how he dramatised the little-known realities of the surveillance state, making clear what government intelligence agencies have known for decades.

Orwell was not wrong in his predictions. In a sense, we are now all Winstons at the mercy of the surveillance state. Although GCHQ are not the Thought Police (and Theresa May is not yet Big Brother), proper regulation and control over surveillance activities is needed to ensure that we never remotely approach that authoritarian model. Therefore, while government surveillance may accomplish unrecognised wonders for our national security and defence against terrorism, it must always remain within a tightly controlled remit. In turn, surveillance alone will never quash extremism. A multi-faceted and wide-ranging approach is needed to tackle the issue at its core

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026 Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026

Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026 News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026

News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026 Comment / ‘Don’t worry, I barely revised’: the effort behind performative effortlessness11 March 2026

Comment / ‘Don’t worry, I barely revised’: the effort behind performative effortlessness11 March 2026 News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026

News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026