How fashion becomes a means of projecting and protesting power

Rachel Elliman dives deep into how fashion has been used to influence politics throughout the centuries

Inevitably, whether you like it or not, we judge people based on how they present themselves to the world through the clothes they wear. Therefore, the fashion choices of leaders, politicians, and activists are essential in their attempts to project and protest power. After returning from a diplomatic tour of Latin America in Summer 2023, Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez summarised this idea on her Instagram story, stating that, “Dress is a form of communication… the way one dresses sends many messages at once,” speaking to how clothing can reflect political ideas and ideology.

From Ancient Egypt to the present day, fashion has always been political. Pharaohs often adorned themselves in distinctive headdresses to reflect themselves as the embodiment of divine authority, symbolising their political and religious power. They also incorporated animal skins such as lion’s tails, which they hung from their belts, into their outfits to emphasise their strength.

“Historically, fashion has been essential in protesting and rejecting power”

Later, these individual expressions of strength through dress were transformed, by leaders, into collective fashions that visually represented the power, unity and identity of the nation. In the late 18th and early 19th century, royals like Sofia Magdalena, the wife of King Gustav III of Sweden in the late 18th and early 19th century began implementing nationalist elements into the dress code of Europe’s royal courts. She introduced prescribed court dress in 1772, then named the “national costume.” It bore a distinctive black and white striped sleeve that became the most important and iconic element of Swedish women’s court dress.

However, historically, fashion has been essential in protesting and rejecting power. England’s suffragettes, who fought for the right to vote for women in the early 20th century, dressed smartly, practically, and in a way that projected effortless femininity in an effort to push back against the media’s disagreeable portrayal of them as masculine and frumpish. They dressed uniformly, expressing comradery in Pethick-Lawrences’ suffragette colours —purple for loyalty and dignity, white for purity and green for hope —featured on the iconic sash.

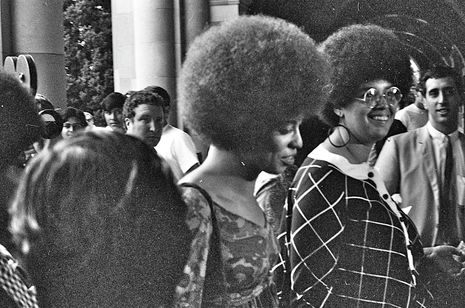

Similarly, activists during the Civil Rights and Black Power movements of 1960’s America used fashion, including symbolic hairstyles, accessories, and clothing to convey their Black pride, combined with a strong push for racial equality. Embracing traditional elements of their African heritage, such as the use of Kente cloth in clothing designs and natural hairstyles like the Afro, they aimed to prove that Black was beautiful, and they were proud of their heritage that white Americans used to justify denying them rights. These fashion statements became fused into American culture and the cause for equality, and today serve as a constant reminder of political progress through activism.

“Embracing traditional elements of their African heritage, such as the use of Kente cloth in clothing designs and natural hairstyles like the Afro, they aimed to prove that Black was beautiful”

The political nature of fashion has only been exacerbated by social media, which amplifies the reach and influence of fashion statements, revolutionising the way they are consumed and interpreted. After Donald Trump’s assassination attempt in July 2024 and the uproar it caused on social media, a trend emerged among Republicans at the National Convention His supporters wore fake bandages on their ears, mimicking his wound dressing, in a show of solidarity. This trend helps victimise Trump and evokes sympathy, while also serving as a reminder that he survived this attempt, making him appear strong and powerful (which was reflected by a 2% increase in the polls after this event happened).

His now Presidential rival, Kamala Harris, also uses fashion to reflect her political ideology. She is often spotted sporting affordable, quintessentially American brands, most notably Converse Chuck Taylor sneakers, which emanate relatability and relaxedness. Harris does so to appeal to working and middle-class voters, her dress remaining nationalistic in its own way whilst speaking to her more left-wing ideology. This harkens back to the 1960 campaign trail, where the fashion icon and wife of presidential candidate JFK, Jackie Kennedy, faced criticism for her “un-American” fashion choices, in her display of French couture, such as Dior and Chanel. She was then told by JFK to only wear American designs, emphasising how nationalism and fashion intersect and can significantly impact the polls.

Even in our lives at Cambridge, fashion is used to counter authority and stand up for marginalised groups. In 2023, for their Black History Month dinner Homerton College hosted Naomi Campbell, the supermodel who led campaigns to improve diversity in the fashion industry. Campbell’s efforts remind us of the inequality still prevalent within the fashion industry and how important it is to celebrate the diversity and representation that she - and so many - have brought to these industries. Her appearance in a historically white institution, that both benefited from and contributed to the enslavement and marginalisation of Black people, emphasises how important it is to keep promoting representation in the fashion industry.

News / Eight Cambridge researchers awarded €17m in ERC research grants27 December 2025

News / Eight Cambridge researchers awarded €17m in ERC research grants27 December 2025 News / Downing investigates ‘mysterious’ underground burial vault 29 December 2025

News / Downing investigates ‘mysterious’ underground burial vault 29 December 2025 Lifestyle / Ask Auntie Alice29 December 2025

Lifestyle / Ask Auntie Alice29 December 2025 Sport / Hard work, heartbreak and hope: international gymnast Maddie Marshall’s journey 29 December 2025

Sport / Hard work, heartbreak and hope: international gymnast Maddie Marshall’s journey 29 December 2025 Interviews / Meet Juan Michel, Cambridge’s multilingual musician29 December 2025

Interviews / Meet Juan Michel, Cambridge’s multilingual musician29 December 2025