Neil MacGregor: History, Faith, and Dürer’s Rhinoceros

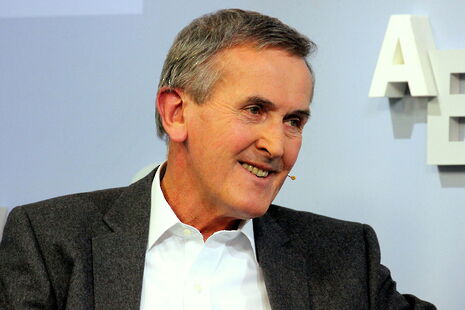

The former Director of the British Museum discusses the historical relationship between faith and society with Josh Kimblin

Historical objects are mute; without a historian to contextualise them and elucidate their connections, they remain voiceless. Fortunately, Dr. Neil MacGregor is a master of historical ventriloquism. He has a rare capacity to give voice, with an object and a few hundred words, to both the detail of individual endeavour and the broad sweep of history.

Having served as Director of the National Gallery and the British Museum, MacGregor designed the widely lauded History of the World in 100 Objects. His latest project concerns the relationship between faith and society – the subject of a recent guest lecture at Wolfson College. Speaking ahead of the event, MacGregor describes the two 17th century images which he intends to ‘ventriloquise’.

The first depicts the destruction of a Huguenot church in 1685, which was pulled down after Louis XVI revoked the liberties of France’s Protestant minority. The second is a 1682 Japanese government notice, offering rewards to anybody who turned in persecuted Christians.

“In both cases, strongly centralising governments emerged from a period of civil war, identified an ‘enemy within’ and attempted to extirpate it in very comparable ways,” he explains. “I’m offering some reflections on those events and considering their current significance.”

How does he interpret the modern-day impact of Louis XIV’s persecution of the Huguenots, then?

“I’m not interpreting but asking questions,” he corrects gently. “Something very specific happened in France in 1685. It was decided that the French state would not tolerate something which regarded itself as a semi-autonomous community, with its own patterns of behaviour and its own rules.”

“The idea that the French state can tolerate individual citizens but not communities has been a strong continuity. The question is: does 1685 mark the beginning of a pattern? French Jews and Freemasons experienced similar reactions [during] the Third Republic, for instance. Does it help explain why today’s France has more difficulty dealing with its Islamic population than any other European country?”

This is an interesting, if provocative, thesis. What features of contemporary France can be linked to this potential trend?

“The French state’s insistence on not identifying people as anything other than French citizens,” MacGregor suggests. “In contemporary France, politicians are reluctant to discuss the Maghreb communities in Paris whereas British politicians find it natural to speak about Bangladeshi or Kashmiri communities…there is a great reluctance to acknowledge that people can have more than one identity.”

MacGregor’s analysis is not purely Euro-centric, however. “The parallel with Japan is very interesting,” he continues. “Like France, Japan in the 1680s moved towards a strong, central state after civil disruption. The identification of Christians as foreign and not ‘properly Japanese’ was part of the closing of Japan and the construction of a unitary identity. This remains a big issue today: how should Japan deal with immigration?”

Can studying such events guide our future approaches to diversity? MacGregor demurs: “The purpose of examining these events is more to help us understand why France responds to this problem differently, as compared to Britain or Germany.”

“However, there is so much public debate about how ‘Europe’ should deal with its Islamic population. That’s not a proper formulation of the question: ‘Europe’ doesn’t deal with it; different countries deal with integration in different ways, partly according to their historical patterns.”

MacGregor has previously suggested that Britain and France could be more self-critical of their histories and follow Germany’s lead in confronting its national successes and failures: could Britain begin that process by reviewing its history of religious and cultural integration?

“It could be a start,” MacGregor observes cautiously. “Germany has been exemplary, over the last thirty to forty years, in critically examining its history to make better future decisions. The idea of a Erinnerungskultur [a ‘culture of remembrance’] is remarkable: there is a political awareness of a need for a culture of memory, positive or not.”

“They see history very much as a lesson; there is a willingness to recognise national political failure in a way which the British and French don’t. In our case, a political impetus to reevaluate our historical relations with Ireland would be a good start.”

“Germany has been exemplary, over the last thirty to forty years, in critically examining its history to make better future decisions”

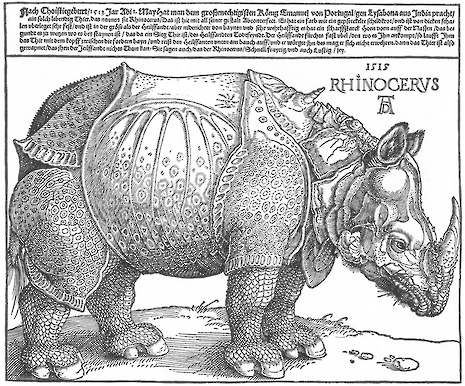

To MacGregor, history is more than an exercise in social didacticism. It is a futile but necessary search for accuracy, exemplified in his favourite British Museum object – Dürer’s famous Rhinoceros print.

“Dürer never saw a living rhinoceros; he was working off second-hand reports,” he explains. “He had to process that information to create an image. That’s a superb model for our studies of the past. We have to turn fragments of information into an impression and, of course, that impression is wrong – like Dürer’s rhinoceros. It’s a wonderful emblem for a necessary struggle with the past – a Sisyphian struggle in which we will always fail.”

Despite apparent defeatism, MacGregor is actually optimistic about the historian’s task: “At the conclusion of Goethe’s Faust, the Angels tell us “He who strives on and lives to strive/ Can earn redemption still.” Humans err every time they strive and struggle, but only people who strive and struggle can be saved. We’ve got to study our pasts and we know we’ll get things wrong. But that’s never a reason not to try.”

Indeed, as MacGregor proves, we can draw profound human truths from our histories; the objects can be made not only to speak, but to sing

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026 Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026

Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026 News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026

News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026 Comment / ‘Don’t worry, I barely revised’: the effort behind performative effortlessness11 March 2026

Comment / ‘Don’t worry, I barely revised’: the effort behind performative effortlessness11 March 2026 News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026

News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026