We need a liberal fightback

In Britain, Europe and America the populists are gaining power, but where is the opposition?

For a brief moment this week, it appeared that the House of Lords might prove an ally of the 48 per cent. It is an odd couple when you think about it, with some polls, for example an Ipsos Mori one conducted last year, showing significant house reform approved by over 70 per cent of test subjects. There was hope among Remainers that the Lords might prove a sticking block for the government’s Article 50 bill, with the make-up of the upper house being much more balanced than the Conservative majority in the Commons. However, this hope was soon dashed and the government continues to plough, or rather stagger aimlessly, towards a hard Brexit. The fact, however, that those on the Left began hoping that the Lords might provide some opposition reveals the extent of the problem at Westminster. The vote on the amendment which would secure the status of EU nationals working in the UK was rejected by the commons with six Labour MPs defying the whip and supporting the government. With the Tories bending ever to the right of their party in an attempt to win the UKIP vote, the need for an effective opposition has never been greater.

“Where is the liberal fightback we Remainers and lefties were promised?”

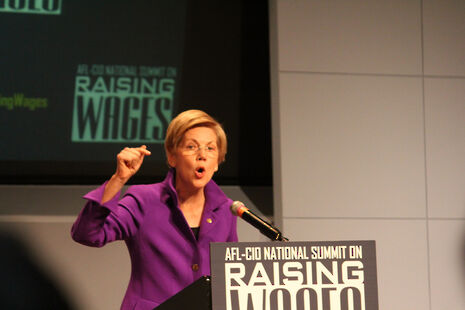

So where, then, is the liberal fight back we Remainers and lefties were all promised? With Labour marginalised, being far too busy shooting itself in the foot or stabbing each other in the back to make real inroads, there is little in Westminster offering any hope to the Left. The same thing can be seen in America, where the Democrats have gone silent. Other than individuals like Elizabeth Warren, the leaders of the DNC have fallen away leaving the media to fight it out with the omnishambles of the Trump administration.

Is it then to the Liberal Democrats that we put our hope in? Tim Farron is running a party on the idea of a second EU vote, an idea, while appealing superficially to many, is actually wholly impractical and would be seen, even if perhaps unfairly, as an affront to our democracy. Moreover, with nine seats, the extent to which the Lib Dems can be an effective opposition is limited, in this parliament at least. The same is true of UKIP, who following the Brexit vote and the resignation of their only popularly known figure and former leader, Nigel Farage, seem an uncharismatic and weakened force.

“were it not for the dire state of the current Labour Party, the Conservatives would appear a weak and divided government”

What about the SNP? With 54 seats, they cheerfully announce that they are the new opposition to the Tories. Having a united party, a confident leader and a strong majority in Scotland, they represent what is merely a dream for Labour voters up and down the UK. What’s more, on the face of it all, many of their policies sound comfortably left of the Conservatives, with pledges in their manifesto to raise the national minimum wage to £8.70 and increase the number of affordable homes. However, the SNP are on other levels a conundrum, struggling in similar ways to UKIP. While they’ve run on other policies (unlike UKIP they have been able to come up with a little more than leave the EU and bring back smoking in pubs) there has always been an elephant in the room: Scottish independence. This elephant was outed this week and has caused an inevitable back lash and an ensuing war of words between May and Sturgeon. This unfolding and contentious debate is likely to dominate British politics over the next parliament, thus making the SNP less of an effective voice on social reform and injustice and more of a one-trick pony, less looking to challenge the government for the good of all Britain, but instead turning in on their core, Scottish support.

With the SNP thus effectively ruining any chance they had at being the voice of opposition, whom do we turn to? Following the Brexit vote, the capitulation of the Parliamentary Labour Party and the outright inability of the Conservatives, the news was flooded with left-wing activists arguing that this was our time to unite and fight back as a coherent left-wing movement. However, in real terms, what steps have actually been taken?

There are weaknesses across both sides of the house: were it not for the dire state of the current Labour Party, the Conservatives would also appear a weak and divided government. The reverse on National Insurance rises and the rebellion over grammar schools are evidence of the deep divides upon the Tories. It would be easy to grow fatalistic at the growth of right-wing populism with the rise of Trump and Le Pen. However, as with Austria last year, the Netherlands last week or even the current rise of Macron in France, there is strength left in populism’s liberal opposition. Let’s not cling to the Lords for our opposition, or to the tweets of Ed Miliband (entertaining thought they are), but form a politics which reflects the complex realities of modern-day Britain.

Time for crap excuses hotline: press 1 for economic downturn;2 for not that nic rate; 3 for blame DC; 4 for not free for interview.

- Ed Miliband (@Ed_Miliband) 8 March 2017

We deserve a politics which engages across party lines and constituency boundaries, away from people’s prejudices and a London focus, a movement which could turn away from Parliament, and towards popular participation is one which can truly claim to be an opposition party

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025 News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025

News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025 News / Uni Scout and Guide Club affirms trans inclusion 12 December 2025

News / Uni Scout and Guide Club affirms trans inclusion 12 December 2025 Comment / The magic of an eight-week term15 December 2025

Comment / The magic of an eight-week term15 December 2025 News / Cambridge Vet School gets lifeline year to stay accredited28 November 2025

News / Cambridge Vet School gets lifeline year to stay accredited28 November 2025