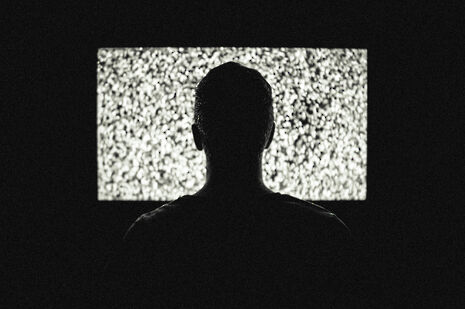

Mainstream media has failed. We’re in a new age of news

Columnist Guy Birch questions the new landscape of social media generated news

At the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in the mid 1960s Joseph Weizenbaum developed a language processing computer program called ELIZA. This program simulated conversation through ‘pattern matching’, and responded to its users as if it understood each of them individually. However, this was merely a simulation, an echo chamber. ELIZA only asked generalised questions and had no way to contextualise the information its users gave. It was, in effect, merely rewording and repeating what test subjects themselves had offered up as well as encouraging them to continue typing, giving up more personal information. Many, most famously Weizenbaum’s secretary, found ELIZA’s well known DOCTOR script to be a comforting and human like program. After a few minutes' use, she asked if Weizenbaum would mind leaving the room suggesting she had formed a personal connection with the program and that she would need privacy to finish the test despite Weizenbaum’s insistence to the contrary.

“the vast number of news articles, blogs and books available online were supposed to liberate a generation with free, almost limitless information”

Fast forward to 2017 and our relationships with social media reveal clear similarities with such programs. Social media and the vast number of news articles, blogs and books available online were supposed to liberate a generation with free, almost limitless information. However, much like ELIZA, such programs, perhaps most notably Facebook and Twitter, have become inverted echo chambers of like minded individuals, rather than forums of contrasting views, ideas and people.

I only know four people who voted Leave in the European Referendum in June last year. Only two of the four were students at Cambridge. Following the Brexit vote and the election of Donald Trump, my timelines and newsfeeds were rammed full of shocked, angry and concerned voices. They sounded like me. They had the same worries about what Trump’s election might mean for the environment, or for human rights, or what Brexit might mean for students from the European Union, or for science research funding, not to mention the price of Marmite. This is a dangerous development in how we consider politics, discuss ideas and receive our news. Rather than unlocking new ideas, across all seven continents, they have made us ever more insular, trapped within our own bubbles, with like minded and (in my experience, during 2016 at least) deeply confused ‘friends’ and ‘followers’. Ironically, Facebook has recently decided to change its ‘Add Friend’ button, to ‘Connect’. This rather tokenistic move serves only to underline the lack of a genuine connection we have to our politics, our wider communities and the nation more generally. We might indeed wonder, whether we truly ever leave the ‘Cambridge Bubble’ during holidays when our online accounts are so intertwined?

“We might indeed wonder, whether we truly ever leave the ‘Cambridge Bubble’ during holidays when our online accounts are so intertwined?”

According to a 2016 survey by Pew Research Center, 62 per cent of U.S. adults get news from social media, with 18 per cent of them doing so on a regular basis. This is up from a similar survey from 2012, which found that 49 per cent used social media to get news. It would perhaps be interesting to see the break down in ages here, I would imagine that the 18-30 year-old demographic would reveal a number far greater than 62 per cent. Regardless, it is clear that sites like Twitter and Facebook bear, therefore, an enormous task, made greater with a decline in print journalism and an uncertain future for mainstream media.

However, the format and structure of these sites makes using social media for news a mine field. For example, Twitter’s 140-character rule effectively means that any complex argument is necessarily reduced to headline, binary and often inflammatory statements. Equally, the anonymity offered by popular social media sites means that statements go unverified, arguments unanswered and lies uncorrected. This format has been used masterfully by Trump since his announcement to run back on the 16th of June 2015. But now, when we receive more information about Trump’s policies, cabinet appointments and reactions to the seemingly endless number of scandals online than through any other avenue, the role social media plays in politics has reached a critical point. This is perhaps best highlighted in Trump’s choice not to take questions from CNN at his first press conference as President-Elect, a decision which perhaps signifies an uneasy omen of what his administration will mean for traditional political journalism. This point was furthered in Trump’s interview with Michael Gove for The Times this week, where he suggested that his Twitter presence would continue after his inauguration, making him the first leader of a major world power to bypass and marginalise journalists and the traditional media-political apparatus by reaching out directly to his ‘followers’.

News through social media is, therefore, here to stay. 2016 proved to be a year in which traditional means of media and communication proved incapable, and a year in which our so-called limitless ability to consider, read and share ideas from around the world was proved false. 2017, I hope, can be a year where we acknowledge those shortcomings and find new means of voicing political and social concerns, if only to avoid falling deeper into our own online ‘bubbles’ and further from a global reality

News / Right-wing billionaire Peter Thiel gives ‘antichrist’ lecture in Cambridge6 February 2026

News / Right-wing billionaire Peter Thiel gives ‘antichrist’ lecture in Cambridge6 February 2026 News / Man pleads guility to arson at Catz8 February 2026

News / Man pleads guility to arson at Catz8 February 2026 News / Epstein contacted Cambridge academics about research funding6 February 2026

News / Epstein contacted Cambridge academics about research funding6 February 2026 News / John’s duped into £10m overspend6 February 2026

News / John’s duped into £10m overspend6 February 2026 News / Cambridge students uncover possible execution pit9 February 2026

News / Cambridge students uncover possible execution pit9 February 2026