In pursuit of the perfect gallery placard

Otto Bajwa-Greenwood muses on the difficulty of writing museum labels

In the documentary Ways of Seeing, John Berger introduces the reader to one of the most famous paintings by Vincent Van Gogh: Wheatfield with Crows. In the image, black crows trace a turbulent, stretched blue-black sky into the far right corner; thick and expressive lines of yellow paint lean with the strong gust of wind; the central wheatfield is split by a meandering dirt road that appears to vanish into nothingness. Now, ask yourself, is this a painting of defiance and hope, capturing the portends of death clear for the light of summer, or one of futility and defeat, ushering in the abyss?

Turning the frame, Berger shows the image again. But this time, scribbled beneath, includes the caption: “This is the last picture that Van Gogh painted before he killed himself”. Although later proved factually inaccurate (the actual last painting is believed to be Tree Roots), what I have just regurgitated above is perhaps the most famous example of the importance of context in shaping our understanding of the meaning of a piece of art. As Berger goes on to humbly suggest, “It is hard to define exactly how the words have changed the image but undoubtedly they have”.

“Instead of the viewer trying to appreciate a work of art, they are presented with authoritative information that undermines individual insight”

Despite Berger focusing in on a particularly dramatic instance of contextual information, his attention towards the significance of object captions alerts us to how such para-artistic markers alter and redefine our interactions with works of art. This small label often beneath or to the side of a work is responsible for not only instructing the viewer of the artist behind the masterpiece, but typically informs them of the piece’s title, occasionally its dimensions, and sometimes the medium used to create it. Captions also often include an enriching analysis of the work – perhaps a few sentences, at times as much as a short paragraph – to enhance the viewer’s appreciation and understanding. These accompanying explanations can make or break a viewer’s enjoyment. You might leave the gallery feeling gratified, departing with the internal glow of cultural expansion, or leave confused, frustrated, and alienated. Inspecting some of the galleries around Cambridge, along with research into the processes of artistic labels at some of the major museums across the world, I have tried to answer some of these key questions.

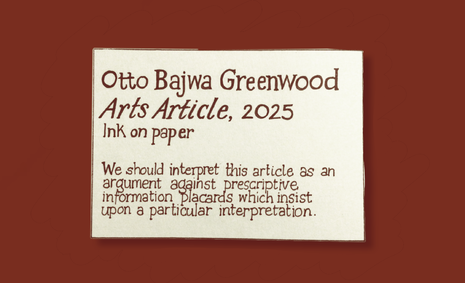

There is debate as to whether descriptive object captions should be included at all. Critics of traditional labels suggest that contextual and analytical information risks constraining interpretive possibilities. Instead of the viewer trying to appreciate a work of art, they are presented with authoritative information that undermines individual insight. Such habits cultivate an over-reliance on textual information, privileging the identity of the artist or the ‘meaning’ of their work over the material and aesthetic qualities of the object. For this reason, some scholars have even labelled supplementary explanations as ‘tombstones’ for their discouragement of independent insights. Gallerie V (located opposite St. John’s) seemingly favours this approach, preferring more moderate and brief descriptions.

However, criticisms of interpretative captions also likely come from those who possess a pre-existing (and privileged) understanding of the art on display. The democratising potential of art should be an important consideration, especially in the creation of a public space. Galleries should seek to aid a viewer’s experience, alerting them towards important history, artistic biography, techniques, and themes in an effort to benefit their experience. Ultimately, you have to start somewhere.

“Captions should seek to push audiences into the world of art criticism”

Expanding upon this point, the content held within art labels is also significant. Leaning on the side of accessibility, the V&A have outlined their three rules to ensure effective communication in their captions, including: an ‘active voice’, the rule ‘write as you speak’, and keeping text ‘short and snappy’. All of these guidelines are designed to “write gallery text that is captivating, illuminating, and comprehensible for a wide audience”. While the V&A themselves claim that “we do not have to ‘dumb down’ our scholarship and collections” to achieve this goal, some critics would disagree. It is not merely a question of accessibility, but also about social mobility. This doesn’t mean galleries should make their detail as verbose as possible, minimising all engagement, but captions should seek to push audiences into the world of art criticism. I found that the Fitzwilliam’s captions balance these demands well. Without inundating the viewer with obscure terms, captions both introduced me to new interpretations and reinforced some of the previous knowledge I had already acquired.

Finally, another important consideration over object labels is in the acknowledgement of cultural or national ownership. At risk of moving into debates over the repatriation of artefacts, the ways in which art labels commemorate certain cultures or recognise the covetous history of colonial acquisition is similarly significant. Wim Pijibes, the former director of the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, emphasised this fact at the Oxford Union in 2017. In his speech, Pijibes supported the concerted effort of the Rijksmuseum to relabel and rewrite ‘Eurocentric vocabulary’. According to Pijibes, this work has opened accessibility to a “global audience” and given back ownership “not to countries but to people,” allowing all to relish in the art’s “global heritage”. Post-colonial critics have also articulated alternative practices to consider when contextualising art. For one, the neutral term ‘collected’ – which glosses over the power asymmetry involved in colonial interactions – should potentially be replaced with terms like ‘taken’, ‘removed’, or ‘stolen’. Additionally, collections might reference perspectives or voices from descendant communities, not just those who are a part of the institution.

There is no right way to present object captions. Even going straight from established collections to touring exhibitions in the same gallery, one will notice significant differences in presentation. But hopefully a greater awareness of the considerations taken when displaying art labels will help to enrich your viewing experience, and allow you to more thoroughly contemplate the space the art is presented in, as well as the art itself.

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026 News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026 News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026

News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026 News / CUCA members attend Reform rally in London20 February 2026

News / CUCA members attend Reform rally in London20 February 2026 News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026

News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026