The insane genius of Mervyn Peake

Sydney Heintz explores the methodical madness of Mervyn Peake’s art

Mere months before the 1911 Revolution, Mervyn Peake was born on the top of Mount Lu, in Kuling, China. The child who would become the author of the Gormenghast trilogy spent the first decade of his life attending Tientsin Grammar School, until the family immigrated to England, where they stayed for the rest of their lives. Nonetheless, feudal China left its mark on Peake: as his son, Sebastian, notes in a BBC documentary on the artist, China “underl[ies] the edifice of Gormenghast”. Anthony Burgess similarly remarks that the novels are “a work of the closed imagination, in which a world parallel to our own is presented in almost paranoiac denseness of detail.” Closed this world is indeed, with its maze-like fortifications, aristocratic successions, and obscure systems of self-legitimisation. No one in Peake seems to know why things happen the way they do – and yet, there is the deep, Qing-like sense that they must go on.

It is precisely this sense of enclosure – entrapment, even – that Peake’s drawings bring to life. The sketches seem to dip in and out of darkness, plunging into obscurity before resurfacing in the conscious realm. His lines are precise as they are plentiful: they blend bodies together (The Mariner & The Dead Albatross), stretch pruning lips (Life-in-Death), and capture the Dickensian grotesque (the Bleak House series). On a commissioned visit to the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, Peake saw an affinity between his drawings and the prisoners – both were caught between life and death. It was an experience he never quite recovered from. In his poem, ‘The Consumptive, Belsen 1945’, he writes, “Is this my traffic? From schooled eye to see […] / The ghost of a great painting […] In this doomed girl a tallow?” It was, in Sebastian’s words, his “heart of darkness” – a moral abyss from which the likes of Steerpike would emerge in his novel Titus Groan.

“The sketches seem to dip in and out of darkness, plunging into obscurity before resurfacing in the conscious realm”

When, in 1941, he was asked to illustrate The Hunting of the Snark, Peake’s response was to study the technique of artists he admired, including Hogarth, Blake, and Goya. A long and successful career followed this, with his illustrating The Rime of the Ancient Mariner (1943), Alice in Wonderland (1946), Bleak House (commissioned 1945, published 1983), and Treasure Island (1949), to name but a few. A gifted writer himself, Peake accepted contracts with an author’s respect for the written word, believing it required one to “subordinate [one]self totally to the book, and slide into another man’s soul.”

This ethos was put to the test in 1943 when the Ministry of Information sent him to the Chance Brothers factory in Smethwick, near Birmingham. There, Peake produced a series of works depicting glassblowers manufacturing cathode-ray tubes for wartime radar systems. But the figures in The Glassblowers are engaged in more than mundane labour: they participate in a ritualistic dance of fire and form. In a talk on the BBC a few years later, Peake described an artist’s duty as that of “seeing”: in his words, “to receive and report what his eye observes”. A kind of truth-teller, an artist should never seek to interpret the world around him; his role, in Peake’s view, was to relay, transmit, illuminate.

“Caught between madness and genius, his work asks us to re-evaluate our claims to sanity within very narrow confines, often at the expense of the stability we take for granted”

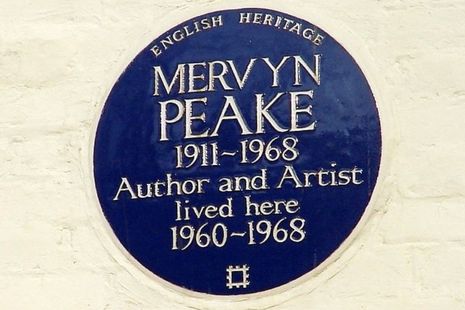

Shortly after moving to the island of Sark in 1946, Peake’s health took a turn for the worse, especially when his play, The Wit to Woo, was negatively received by critics in London. This marked the onset of a major nervous breakdown, aggravated by early symptoms of dementia. Given electroconvulsive treatment to no avail, he quickly lost the ability to draw and write coherently, the drafts of Titus Alone (currently held in The British Library) bearing witness to this. Among his last works were illustrations of Balzac’s Droll Stories (1961) and his own poem The Rhyme of the Flying Bomb (1962), before declining health drove him to a care-home near Oxford.

And yet Peake cannot be counted as one of Freud’s patients. Nor is he a product of the American supernatural (Poe). As a friend once observed to me, he has an almost Renaissance madness. In his drawings and novels, Peake captures a civilisation which has lost the ability to understand its own methods of procedure; which sees power defined through ritual, and gothic in the ordinary. With Steerpike’s slow ascension through the castle in Titus Groan, we have the Revolution exploiting the stagnation of a regime which has been destabilised by a weak juvenile succession, as well as centuries of internal resistance to change. It’s as much a political insanity as a psychological one – indeed the two go hand in hand when, begging for mice, Lord Sepulchrave transforms into an owl in the Tower of Flints. Peake’s case then is a particular one: caught between madness and genius, his work asks us to re-evaluate our claims to sanity within very narrow confines, often at the expense of the stability we take for granted.

News / Right-wing billionaire Peter Thiel gives ‘antichrist’ lecture in Cambridge6 February 2026

News / Right-wing billionaire Peter Thiel gives ‘antichrist’ lecture in Cambridge6 February 2026 Features / From fresher to finalist: how have you evolved at Cambridge?10 February 2026

Features / From fresher to finalist: how have you evolved at Cambridge?10 February 2026 Film & TV / Remembering Rob Reiner 11 February 2026

Film & TV / Remembering Rob Reiner 11 February 2026 News / Churchill plans for new Archives Centre building10 February 2026

News / Churchill plans for new Archives Centre building10 February 2026 News / Epstein contacted Cambridge academics about research funding6 February 2026

News / Epstein contacted Cambridge academics about research funding6 February 2026