Glenn Ligon at the Fitzwilliam: revelations ‘all over the place’

The American artist is given the curatorial keys to the Fitz, which he uses to go to places never visited by the gallery before

If you have ever visited an art exhibition, it would only be natural to assume that you would walk into a room and be shown piece by piece the practices of an artist. What is most striking about the new Glenn Ligon (born in New York, 1960) exhibition at the Fitzwilliam Museum is that it is, as its title suggests, all over the place. The purpose of the exhibit is not only to display many of Ligon’s personal works as an African American exploring social justice, Black history, sexuality and gender, but also to highlight a side to the Fitz’s pre-existing collection that we have yet to see.

“Ligon deliberately removes artworks, exposing the shape of what previously hung there”

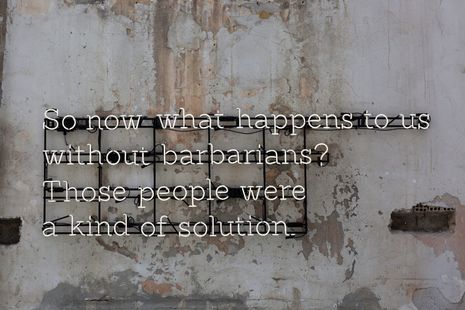

In an effort to draw attention to, discuss, and untangle the difficult and complicated histories associated with many of the Fitz’s possessions, Ligon has curated several “interventions” which re-display the gallery’s works, challenging our initial assumptions around them. A visitor’s first face-to-face experience with Ligon’s tinkering is on the front steps: huge glaring white neon reliefs cling to the pillars of the museum’s grand entrance. A repeated phrase reads: “And now what’s to become of us without barbarians. Those people were a solution…“. Only one relief actually finishes the line: “…of a sort”. The phrase, taken from Greek poet Constantine P. Cavafy’s poem ‘Waiting for the Barbarians’ is a stark and poignant introduction to an exhibition unafraid of focusing on the hard-hitting truths, be it social justice, Black heritage, or “the spoils of the empire”.

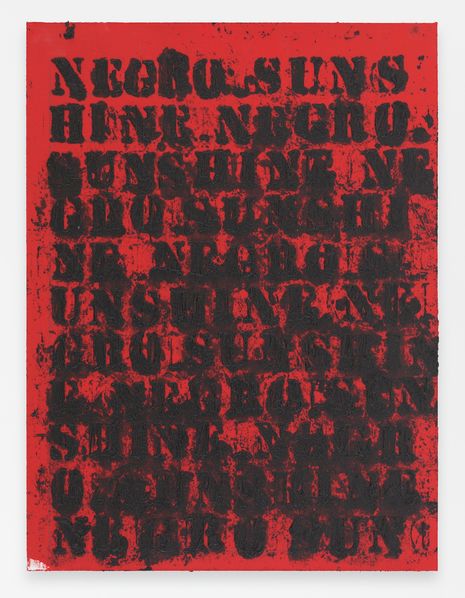

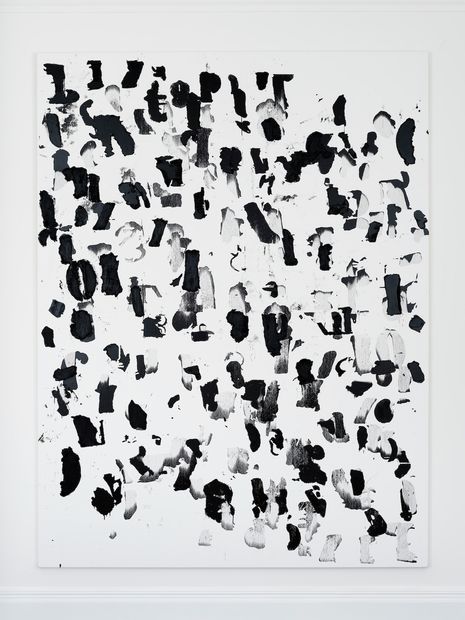

Ligon, whose artistic practices span over 30 years, first merges with the Fitz’s collection within its medieval section. More specifically, within the only painting in that entire room to include someone of African descent: Adoration of the Kings (c.1520). It seems, as Ligon notes on a bright red placard (a tool used throughout the exhibition), to present Balthazar, one of the three magi, as Black; he links this to the common Northern European tendency to use Balthazar as a symbol for the entire continent of Africa. However, what is most captivating about this choice of accompaniment to Ligon’s own print ’Study for Negro Sunshine (Red)’, is that there are no other paintings on that entire wall. Ligon has deliberately removed all previous artwork, exposing the “ghostly gold shapes” of what previously hung there. It’s a rare thing for an exhibition to leave a space almost entirely blank. And yet Ligon’s decision perfectly highlights the historical indentations museums can leave with the paintings that they choose not to display.

“Ligon challenges our assumptions about what we see in front of us”

As you follow the little “black suns” of the repeated ‘Study for Negro Sunshine’ print, you arrive at what is normally the entrance to the Fitz’s Dutch and Flemish collection, usually covered with several pieces of their botanical works. But of course, Ligon has turned the typical vibrant floral still lifes into a much more emotive, distressing message. With over 80 paintings, Ligon has overwhelmed the gallery space with incredible expressions of flora and fauna. However, in his description of the space, Ligon cannot help but quote Teju Cole: “There’s almost always trouble in any work of art. That does not spoil our enjoyment of it, it deepens it”. Ligon makes this point, as he explains, to remind the viewer that it’s this kind of display of abundance and wealth that is a museum’s downfall when facing their own acquisitions — their achievements necessitated colonialism and slavery.

The final element of Ligon’s curated tour of the Fitz brings you to his take on Korean Moon Jars. Traditionally made with white clay, Ligon created his “blackish” ones, to highlight the power of colour within cultural norms. He discusses the fact that, while creating his jars in Korea and experimenting with different shades of dark clay, he ended up having many conversations around the true shade of ‘blackness’: while he saw dark greys, deep browns, and indigo blues, his partners simply saw ‘black’. This is perhaps the most revealing intervention staged and curated by Ligon — he challenges our assumptions about what we see in front of us, our impulsive thoughts as to how it should be described, and also the level of value we give it due to those impulses. He pushes us as his audience to see both the beauty and the difficulty in his choice of colour.

The Fitzwilliam Museum has been conscious of its involvement in difficult history over the past several years. The items lying in its storage cupboards have not always been obtained respectfully. However, this exhibition proves that the Fitz, through its collaboration with Glenn Ligon, is willing not only to have conversations around its relationship to that history, but also to give a voice back to those to whom it originally belonged.

By handing the curatorial keys to an artist whose artwork has reverberated across cultures for the past several decades, the museum has brought forth messages that could have been left dangerously in the past. In doing so, the Fitz is embracing a better, stronger future for itself; one that is representative of the history it holds and to the individuals who contributed to it.

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026 News / Gov grants £36m to Cambridge supercomputer17 February 2026

News / Gov grants £36m to Cambridge supercomputer17 February 2026 News / CUCA members attend Reform rally in London20 February 2026

News / CUCA members attend Reform rally in London20 February 2026 News / Union speakers condemn ‘hateful’ Katie Hopkins speech14 February 2026

News / Union speakers condemn ‘hateful’ Katie Hopkins speech14 February 2026 News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026