Cambridge’s missing novel

Jen Price explores why Cambridge lacks an iconic novel of its own, and how it suffers without one

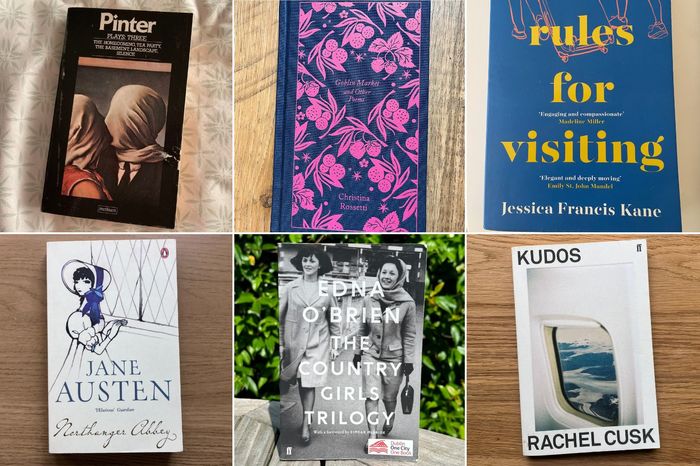

Oxford has Brideshead Revisited. Birmingham has The Rotter’s Club. Bath has Austen’s Northanger Abbey. But when one thinks of Cambridge, there isn’t an iconic novel that has shifted cultural perceptions of our city. So why hasn’t Cambridge been immortalised in literature in the same way as other British cities? From Ted Hughes to A.A. Milne, Cambridge is home to no shortage of world-class authors, but perceptions of the university are shaped more by lists of famous alumni than by their depictions of the place and its people. Would the way people think about Cambridge change if it had an iconic novel?

“Cambridge acts as a bridge rather than as a destination”

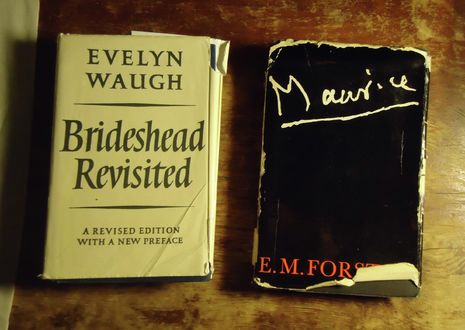

Cambridge does of course feature in famous works of literature, but these depictions often fall flat. In E.M. Forster’s Maurice, Cambridge acts as a bridge to the next location in the eponymous character’s quest for self-discovery, rather than as a destination. In contrast, for Charles Ryder and Sebastian Flyte in Brideshead Revisited, Oxford is a Garden of Eden, a place immune from the pains of the real world. You can see this before even opening the novel, thanks to the subtitle “the Sacred and Profane Memories of Charles Ryder”. Waugh immediately establishes an almost biblical connection between the characters and their place of study. This idea of exclusivity and romanticisation, although not necessarily realistic, is a timeless and commonly-held perception of Oxbridge.

Perhaps the main reason for this difference in tone is the content of the two novels. The principal difference between Maurice and Brideshead Revisited is that whilst Waugh alludes to a homosexual relationship between Charles and Sebastian, Forster openly depicts the experience of a gay man. Consequently, Maurice was censored and not published until 1971 (over 50 years after it was first written). As such, it represented a Cambridge that no longer existed. In the political upheaval of the 20th Century, the city changed drastically: women were admitted as full students, new colleges opened, and social and cultural activities such as the ADC were nurtured.

“Cambridge is just a setting, not a character in its own right”

In Brideshead Revisited, Oxford epitomises the upper echelons of British society, elegance, and debauchery described in the novel. A reminiscent tone underpins Waugh’s memory of Oxford, which he describes as “a city of aquatint. In her spacious and quiet streets men walked and spoke as they had done in Newman’s day”. In contrast, for Forster, Cambridge is just a setting, not a character in its own right. Describing his first year at Cambridge, Forster writes that Maurice “managed to experience little in university life that was unfamiliar”. This bland depiction is devoid of any of the charm of Waugh’s artistic lyricism. And therefore, the Cambridge of Forster’s works is difficult to romanticise.

I considered this question further when I visited the University Library’s Murder By the Book exhibition. Faced with the beloved Detective Inspector Morse, I reflected upon Cambridge’s role in the crime genre, and discovered Lois Austen-Leigh’s The Incredible Crime, a mystery about drug smuggling in a fictional Cambridge college. To be blunt, it doesn’t feel like Cambridge is relevant to the story, (beyond some passages describing rugby matches). In this novel, the fictional Prince’s College is based on Austen-Leigh’s youthful experiences visiting her Uncle, who was Provost of King’s. While reading the novel, it is clear that this Cambridge is the product of a childhood imagination, and it’s difficult to truly connect it to the modern university. Additionally, it acts as a contrast with the plot’s other main location, a country house. This two-dimensional depiction of Cambridge, aside from its other flaws, simply serves as a representation of the city’s exclusivity: a place simply for the rich, privately-educated, landed elite. Considering this, it is unsurprising that this novel failed to become iconic; who would revere a soulless, cold environment filled with soulless, cold people? And from a practical perspective, this novel was out of print for over 70 years, making it impossible for the novel to achieve a similar status level to its Oxford counterparts.

“The reader is relegated to the position of outsider, looking through a window into a static image of university life”

Where Brideshead Revisited succeeds is in its celebration of the things that make Oxford famous. Reading the novel, I felt like a member of Waugh’s exclusive, secret world of Oxford academia. Yet, for novels set in Cambridge, the reader is relegated to being an outsider, looking through a window into a static image of university life. These novels ultimately reinforce the perception of Cambridge as a sterile, unwelcoming environment that is inaccessible to the average reader. Cambridge simply seems less ‘fun’ than Oxford.

That, I think, is the biggest problem with the absence of the ‘Iconic Cambridge Novel’. While the reputation of Cambridge as a whole is unlikely to be significantly impacted by the absence of a quintessentially Cantabrigian novel, on a smaller scale, media can be an intrinsic motivation for applications. 2014 saw a 32% increase in applications to Trinity Hall following the release of The Theory of Everything, despite the fact it was not filmed in Trinity Hall, but in St John’s College, its larger and allegedly more photogenic neighbour. Maybe what small colleges need to boost their applications isn’t an improvement to their quality of teaching, but a stronger presence in popular culture.

Literature and film, not faculty websites or open days, provide most people’s first awareness of Oxbridge. And when it’s so easy to find content suggesting that Cambridge is outdated and unwelcoming, it comes as no surprise that students arriving here feel isolated and out-of-place. It’s time for popular culture to celebrate Cambridge, and reflect its positive atmosphere instead of disparaging it. Like Birmingham’s Benjamin Trotter in The Rotter’s Club, we need someone to run through Cambridge shouting “I love this city!”

News / Eight Cambridge researchers awarded €17m in ERC research grants27 December 2025

News / Eight Cambridge researchers awarded €17m in ERC research grants27 December 2025 News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025

News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025 Comment / League tables do more harm than good26 December 2025

Comment / League tables do more harm than good26 December 2025 Comment / The ‘class’ of Cambridge24 December 2025

Comment / The ‘class’ of Cambridge24 December 2025 News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025

News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025