Varsity’s summer reads

From literary classics to surrealist exchanges, our Arts team tells you what books they’ve taken with them on holiday

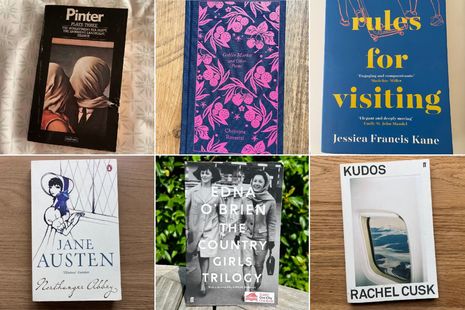

Kudos by Rachel Cusk – Felix Armstrong (Arts Editor)

Cool. Rhythmic. Lasting.

In each of the past few summers, I’ve read one Rachel Cusk novel, rationing them out in the hopes that she can write them faster than I read them. This year I picked up Kudos, the finale of Cusk’s Outline trilogy, a series that dramatically pivoted both her career and the genre of literary fiction. Each of the three are largely similar, subjecting its semi-autobiographical protagonist to the oppressive heat of an unnamed European location and just a few, chapter-length, conversations with fellow travellers. The dialogue dodges masterfully between realism and melodrama, as the slightest questions from the protagonist (who barely speaks) reliably prompt the strangers she meets to embark on multiple pages of soul-searching monologue. People don’t really talk like this in real life, but maybe they want to.

How Fiction Works by James Wood – Madelaine Clark (Arts Editor)

Clinching. Concatenating. Cellular.

I miss or forget parts of How Fiction Works every time I read it. The book’s title is a mammoth claim, and Wood works, unfalteringly, at the level of the microscope. Speaking generally, his thesis is a defence of literary realism, but almost all of Wood’s paragraphs handle a new textual morsel – a paragraph, a sentence, even just a comma – accompanied by neat and rounded thought. I came to feel that the book was some kind of closed-experiment, a series of highly and paradoxically controlled ricochets. He lifts this from The Waves – “the day waves yellow with all its crops” – and plunges into its strange, surprising centre, that smearing verb-noun combination. For Wood, it “conveys a sense that yellowness has so intensely taken over the day itself that it has taken over our verbs, too”. I’m re-reading the book this summer, and I’ll forget lots. Next year, though, I’ll get to read it again.

Devotions: The Selected Poems of Mary Oliver – Heather Leigh (Arts Writer)

Wonder. Joy. Prayer.

Mary Oliver’s poetry is an exercise in noticing. Amid the sometimes deafening clamour of artists having their say, Oliver’s appeal (and the reason that she is such an important poet for the modern age) lies in her ability to listen. Her poems are quiet and that’s what makes them beautiful: she creates space for flowers to unfurl, for birds to sing out of the silence, for trees to talk. She feels overwhelming awe at the ordinary, and from this place blossoms emotional and spiritual connection, and renewal. As Oliver herself says: “attention is the beginning of devotion.”

Nicotine by Gregor Hens – Ben Birch (Arts Writer)

Memory. Addiction. Irreverent.

I imagine you’ve spent the past year working very hard – save the Victorian door stop novels for retirement, spend summer reading something shorter. Nicotine was the last book I read for pleasure and it’s one of the few that I’ve recommended to anyone since. The book is a memoir told through the author’s addiction. It’s unglamorous, funny, and easy to get along with. To Hens, addiction is not a private members’ club – the story will be relatable to anyone who’s never quite got over an obsession, even if it’s been stubbed out and left in the past.

Goblin Market and Other Poems by Christina Rossetti – Emily Cushion (Arts Writer)

Liminal. Biblical. Personal.

Against the odds, Christina Rossetti was a poet. Living in a society oppressed by patriarchy, religion, and morbidity, Rossetti settled into an “isolated devoteeism” which saw her produce some of the rawest poetry the 19th century had to offer. Racked with religious guilt and drowning in forbidden desire, this collection acts as a culmination of Rossetti’s deepest thoughts and experiences. ‘Goblin Market’ remains her most well-known poem with its establishment of femininity’s duality through some particularly juicy fruit images. Equally poignant, though less widely read, is her heart-breaking ‘Echo’, which draws on her typical themes of dreaming and liminality in a romantic retelling of the myth from Ovid’s Metamorphoses. Over 150 years after its publication, we can still attempt to offer solace to Rossetti’s solitude in reading her collected works. After all, through her introspective, heart-on-sleeve verse, Rossetti implores readers for a singular, poetically fundamental thing: understanding.

Northanger Abbey by Jane Austen – Jen Price (Arts Writer)

Lighthearted. Romantic. Silly.

I know Austen is arguably the most famous British novelist of all time, but the true brilliance of her work is criminally underrated. Northanger Abbey is a shining example of Austen’s humour and sarcasm and genuinely made me (and everyone I’ve recommended it to) laugh out loud. This satire of the gothic genre highlights the absurdities of regency England, and Austen’s frequent direct addresses of the reader resemble an episode of The Office or Parks and Recreation rather than the traditional idea of a doorstop-sized classic novel. If you’re looking for a book to read for fun, rather than for the prestige of having read a classic novel, look no further.

The Country Girls by Edna O’Brien – Amie Brian (Arts Writer)

Fierce. Tender. Compassionate.

Charles J. Haughey once denounced The Country Girls by Edna O’Brien as “filth [that] should not be allowed in any decent home,” setting the expectation for what was to become one of the most controversial Irish novels of the 20th century. A novel banned upon its publication in 1960, and subject to several book burnings, The Country Girls has fought for its place as an Irish classic. Within its pages, O’Brien’s novel gently navigates the hidden sexual lives of women in a non-permissive society through the tragic, dreamy naïvete of her young protagonist. Thoughtful, lyrical prose, and expressive dialogue unveils a singularly compassionate exploration of sexual awakening and manipulation. While Edna O’Brien tragically passed just weeks ago, her legacy lives on in this frank challenge to the moral failings of Irish society.

Twelve Years A Slave by Solomon Northup – Niall Quinn (Arts Writer)

Revealing. Raw. Potent.

This is not a light summer read. But it is an important one. Chronicling his time as a slave in the Red River area, Louisiana, from 1841 to 1853, Northup’s prose is something to be witnessed, not consumed. Through his voice, the silenced speak. Capturing in painstaking detail the varied treatment he received by his first master, his day-to-day activities as a carpenter, and the personalities of those around him on the plantation, the witness is made aware of some of the brutal realities of the institution of slavery in the ante-bellum United States. Though Northup hoped to “lead an upright though lowly life” upon his liberation, his legacy – in the form of this narrative – remains nothing short of a historical miracle.

The Homecoming by Harold Pinter – Eve Connor (Arts Writer)

Londoners. Are. Weird.

When I spied a laminated collection of Harold Pinter plays at a library sale, I thought I ought to go for it. At least in theatre, Pinter is a name people know, one of those starry few who can command adjectives about themselves (‘Pinteresque’). His 1965 play The Homecoming stands apart to me for a lucidly tense exchange about a cheese roll. Set in a North London living room, it asks what happens to a family of men without women after the eldest son returns with a wife. Pinter absorbs the reader or audience wholly into his world, so that even as The Homecoming tears the curtain down on itself towards its final movement and succumbs to a raw, uncomfortable strain of strangeness, you cannot dismiss it. It is mundane, threatening, and absurd. But then again, most family reunions are.

Rules for Visiting by Jessica Frances Kane – India Hansra (Arts Writer)

Nostalgia. Gratitude. Forgiveness.

This unpretentious novel is perfect for a summer read; with a simple tone and lack of unnecessarily verbose language, this book is one to help you unwind from the hectic Cambridge exam term. Presented from the viewpoint of a middle-aged woman taking leave from her gardening job to visit people once important to her, the book presents a spin on the popular idea of ‘the friends we make along the way’. It presents a deceptively ordinary journey, before revealing that the most simple of pursuits can give way to the most potent of emotions.

The Moviegoer by Walker Percy – Ronan McAuliffe (Arts Writer)

Sweaty. Searcher. Summer.

I read this at the very beginning of summer, and sweated throughout, fingerprinting my copy indelibly. Though set at the beginning of Lent, in the days leading up to and surrounding Mardi Gras, The Moviegoer is full of summer heat. Binx Bolling lives in New Orleans, engages in small talk and affairs, and goes to the cinema until he can’t take it anymore. He leaves town just before the carnival. The book’s central matter is the following journey, which he calls the search. Though apparently aimless, this search gives Binx many chances to daydream, muse and complain. He mucks about on the Gulf Coast and eventually finds God. This is all very beautifully written – in sweltering, sharp, funny American prose. An easy but enduringly thoughtful read, for fans of Dostoevsky, Flannery O’Connor, God, Faulkner, and summertime.

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026 News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026 News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026

News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026 News / CUCA members attend Reform rally in London20 February 2026

News / CUCA members attend Reform rally in London20 February 2026 News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026

News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026