Please don’t take me to court

Josh Pritchard reflects on the rigidity of copyright and its implications for amateur shows

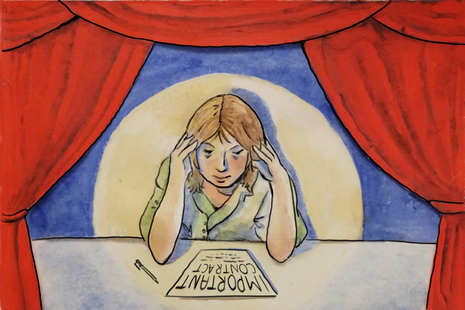

Copyright is a behemoth. A large, unlikable, painfully necessary behemoth that hovers over student producers like an unwanted stench. It’s also something I’m very unfamiliar with, yet still feel an intense desire to not contravene in the slightest – kind of like that teacher you never spoke to as a kid, but who supposedly sent all your friends and their loved ones to detention.

Becoming a theatre producer has given me an understanding of how intellectual property functions in practice, and just how many restrictions accompany it. Those license agreements exist, and they are explicit. No longer can I get mad at amateur shows for ‘sticking with that line’ or ‘not changing that word.’ Instead, my annoyance now shifts to our corporate overlords and the gods of contract law that insist upon every syllable being word-for-word accurate to the original script. To be clear: I am not an expert in copyright law, nor is this a piece arguing against it. As I’ve alluded to, copyright plays a crucial role in safeguarding artists from genuine infringement and ensuring that they’re fairly compensated: a protection creatives have historically lacked. What I am arguing is that amateur performance rights need to be more versatile, and allow for artists to make edits or cuts without the fear of a fine or lawsuit. This will have a variety of benefits, chief among them, giving artists the confidence to amend material that isn’t beholden to the same I.P. laws.

“Why then do many contracts for modern scripts feel the need to insist upon word-for-word recital”

Cambridge’s approach to classical plays are a great example of this. The last two weeks of Easter saw seven different iterations of Shakespearean works. Most I saw were emboldened to cut lines and material which didn’t complement the rest of the piece’s vision – BATS’ Twelfth Night went so far as to put in contemporary songs. Other shows throughout term tweaked lines which could be interpreted as having pejorative meanings in modern contexts: the adjective ‘gay’, for example, held quite a different connotation in the 1900s than it might for the modern viewer. In these cases, the freedom to amend kept audience attention from drifting to alternative meanings that might conflict with the artists’ intended vision. Why then do many contracts for modern scripts feel the need to insist upon word-for-word recital?

It is not difficult to find cases where restriction has hindered a show’s quality. Easter’s [title of show] was a brilliant late show chronicling the rise of four friends within the musical theatre industry: one of my favourite shows of the entire term. What slightly hampered it was the fact that its characters and events were real, and its creators had felt the need to continue adding content to what was clearly an originally snug 60 minutes of fun, light meta-musical theatre. For anyone unfamiliar with the group, however, the show sometimes felt less like a cohesive narrative and more like an ongoing series of personal updates. Had the ADC team been given the power to trim the fat, or utilise an earlier version of the production, I have little doubt it would have resulted in a more succinct hour of entertainment.

“Why keep a line if it risks disrupting what should otherwise flow seamlessly”

Similarly, the incredible cast of one of last year’s Freshers’ Plays, 10 out of 12, were burdened with performing material packed with references entirely foreign to a Cambridge audience. A 2015 script head-over-heels with New York’s bustling theatre scene? Some of those lines might as well have been written in Martian. You can argue this is being pedantic. After all, we don’t go tweaking Singin’ In The Rain when it references His Glorious Night or other works of its era. True. But that’s a script rooted firmly in its historicity. Many modern shows are not. There’s a considerable difference between an important reference landing as a quirky, obscure nod that gathers a polite chuckle, and one so unfamiliar it leaves us completely befuddled. Theatre is one of the few mediums which permits audience adaptability, so why are we not doing more of it?

What differentiates a large change from a small change is open to interpretation, and, thankfully, that’s something for the lawyers and the smart people to sort out. As a humble audience member, however, I still find it glaringly obvious when a script unnecessarily bogs down a director’s vision. But this isn’t unsolvable. Allowing legal flexibility to adapt scripts on a case-by-case basis doesn’t dilute a play’s integrity; in fact, it can enhance it significantly. If the changes don’t work, they don’t work. The play is still a masterpiece (...probably.) But then again, I don’t need to worry much. It’s hard to imagine these legal teams sending the contract-sniffer dogs to monitor amateur productions. So, perhaps, we can look the other way when an actor ‘accidentally’ flubs their lines… every night… coincidentally.

News / Right-wing billionaire Peter Thiel gives ‘antichrist’ lecture in Cambridge6 February 2026

News / Right-wing billionaire Peter Thiel gives ‘antichrist’ lecture in Cambridge6 February 2026 Features / From fresher to finalist: how have you evolved at Cambridge?10 February 2026

Features / From fresher to finalist: how have you evolved at Cambridge?10 February 2026 Film & TV / Remembering Rob Reiner 11 February 2026

Film & TV / Remembering Rob Reiner 11 February 2026 News / Churchill plans for new Archives Centre building10 February 2026

News / Churchill plans for new Archives Centre building10 February 2026 News / Epstein contacted Cambridge academics about research funding6 February 2026

News / Epstein contacted Cambridge academics about research funding6 February 2026