[BLANK] is complex and expressive, but falls short in its experimentation

Emma Robinson reviews the recent Fletcher Players production of Alice Birch’s BLANK.

Disconnect is key in [BLANK]. As numerous brief scenes accumulate into a jarring montage, listeners may seek tenuous narrative links between the different characters and situations. But, ultimately, the scope of these scenes can only be unified in a realisation, not a story: the dawning realisation that social, criminal, medical and charitable systems are not sufficient at supporting women, or their children, when they need help. I was left with the question of whether writing, telling, and sharing life-experiences can offer some hope in itself, or whether that in turn will merely draw another blank.

This disconnect was powerfully extended through Rae Morris’ directorial choice to alter the medium of the original stage-play script. As a radio play, [BLANK] seems to lack even more clarity, as full intimacy with the performers is inhibited. However, simultaneously, radio breaches the comfortable detachment which is normally provided by the experience of theatre-going. Without a visual stimulus, the frequently domestic setting of the play can all too easily be projected onto the audience’s surroundings – their own homes. This results in an oscillating tension between empathy and unknowability.

“The casting process could not have been simpler; everyone who wanted to be involved, was.”

At the same time, as we all know from the experience of countless zooms over this past year, it is an almost unavoidable reality that your mind will lose focus when faces and voices feel distant. But even this is beautifully relevant to the play’s themes, as the desire for distraction when uncomfortable stories arise is as common as it is detrimental and is conveyed in the play’s scenes themselves.

[BLANK]’s tendency towards overlapping voices in fast-paced dialogues gives a sense that no-one is really listening to one another. Movements in and out of small talk, alongside these harrowing stories of death, drugs, domestic abuse, and despair show a willingness to evade the real issue. Small talk most notably keeps allowing the characters eyes to fall and fix upon their physical surroundings – an escape the audience are ironically not given access to – as the characters comment on broken bulbs, ripped pyjamas, magnolia trees, and most frequently (the all-time favourite), the ‘let’s fill the silence with whatever we can’ topic of the weather.

“Although this play could certainly have pushed its experimentation further, it was bold and expressive.”

Indeed, Rachel Leia Devadason’s sound design, which connects the play together, relies heavily upon the natural sounds of birds, rain and wind. At moments it captures the hostility of the scenes. But elsewhere, it captures the exact serenity which is so discordant with the play’s themes. One quote in particular remained with me: when asked, ‘how are you feeling?’, a woman promptly responds that ‘it’s sunny’.

The play’s complexity was not extended to the casting process, which could not have been simpler; everyone who wanted to be involved, was. This supportive inclusivity was a powerful decision, as it enabled the greatest multiplicity of voices and so conveyed the tragic universality of negative female experiences within ‘the system’.

Whilst the potential of silence could have been optimised and it felt at times that the actors were rushing through their lines, not allowing the weight of the stories to settle, overall, the emotion was conveyed effectively. However, in scenes which immediately delved into conflict, rather than having a gradual build in tension, there was a sense that the actors felt obliged to push their voices, straining for emotions that seemed narratively unearned. If the actors had been directed towards a more subtle performance, the audience might have lent into its quietness, and ultimately been moved further by sympathy than momentary shock.

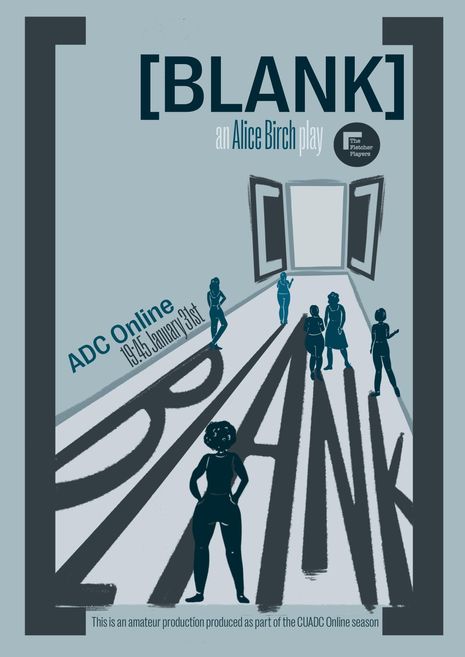

Although this production could certainly have pushed its experimentation further, it was bold and expressive. And while the characters remained faceless, in both the production and Louise Knight’s incredible promotional artwork, we could see in the shadows that their lives cast part of a bigger picture, a larger reality – a [BLANK] that they have the potential to fill as well as become.

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026 News / University Council rescinds University Centre membership20 February 2026

News / University Council rescinds University Centre membership20 February 2026 News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026 News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026

News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026 News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026

News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026