Watch out for your fruit bowl

Jenny Jiang gives an insight into the everyday fruits that can pose lethal threats

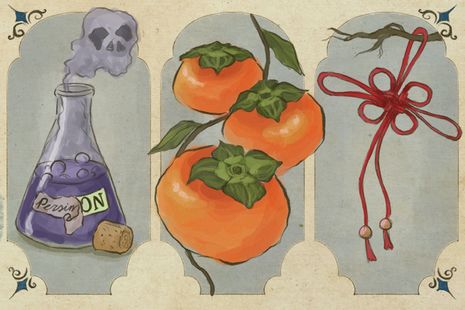

Do you enjoy poison-based murder mysteries but are bored with all of the strychnine, arsenic, and cyanide appearances? Looking for something different? Well, look no further: here is an accessible, everyday fruit, which, if you are not careful, could accidentally kill you. The compounds that are present are not poisonous on their own, but in the presence of certain other molecules – their accomplice, if you will – would lead to some severe reactions… even death.

The dangerous fruit in question is the humble persimmon - a popular fruit in the colder seasons known for its distinctive golden colour. If you are out of season but in need (for whatever reason), lychee’s absurd blood-sugar-lowering ability is a good place to start.

While many different persimmon varieties are growing all around the world, they can be divided into two key groups – astringent and non-astringent (sweet). Astringent persimmons (e.g. Hachiya and Rojo Brillante) are known as soft persimmons – they are meant to be eaten when they are fully ripe. Biting an unripe astringent persimmon causes a bitter, dry, puckering sensation that makes you want to spit it out. By contrast, non-astringent persimmons (e.g. Fuyu, Sharon) stay crunchy and won’t astringe, so they’re safe to eat hard or soft. Most persimmons in UK supermarkets are non-astringent.

“The concentrations in persimmon juice are forty times those in apple juice”

The substance that acts as the villain in persimmons is water-soluble tannin, a type of polyphenol present in many plant species. Polyphenols are natural compounds made of multiple phenol rings; they are found throughout the plant kingdom and often contribute colour, flavour and antioxidant activity. They can also be found in wine, where they add bitterness and astringency. Water-soluble tannins create this dry mouth sensation by binding and precipitating salivary proteins, shrinking the mucus membrane in the mouth and throat. But why doesn’t eating other fruits cause the dry mouth sensation if tannin is also present?

The answer all comes to down dosage. Grapes, pomegranates, apples, and many other fruits contain soluble tannins too, but persimmons have far more. For example, tannin concentrations in persimmon juice are twice as great as in grape juice, ten times greater than in pomegranate juice, and forty times in apple juice. The reason grapes have a relatively high tannin level is due to their high surface area to volume ratio, and tannins tend to accumulate in the skin of fruits. This also explains the dry mouth sensation you get when you chew grapes with thick skin.

The difference between astringent and non-astringent persimmons lies in soluble tannin levels when unripe. Soluble tannins convert to insoluble forms during ripening, which don’t interact with saliva, reducing astringency. Research shows soluble tannin decreases naturally in non-astringent types during growth and ripening. However, in astringent persimmons, soluble tannin steadily increases during growth, remaining high when nearly mature and firm. Conversion to the insoluble form only begins once the fruit softens. This provides the evidence that astringent persimmons need extra time for the tannins to be broken down before they can be eaten, while non-astringent persimmons already have a low tannin level so can be eaten straight off the tree.

“Causing nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and even gastrointestinal bleeding”

So, how can tannin in persimmons kill someone? Dry mouth alone is certainly not sufficient – it’s what happens deeper in the digestive tract. Persimmon tannins react with stomach acid to form dense coagulations or “food lumps” called persimmon phytobezoars. These consist of polymerised fibres, other vegetable matter, and proteins, potentially causing nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. If they grow too large so that your digestive system can’t manage or pass them out, they start to block the gastrointestinal tract, causing intestinal obstruction, upper gastrointestinal bleeding, and even gastric outlet obstruction. Persimmon phytobezoar is the hardest phytobezoar of all bezoars – more densely cross-linked and less porous than those from citrus peels or vegetable fibres – making them exceptionally difficult to break down or pass out without medical intervention.

Despite the high concentrations of tannins present in the not-yet-fully-ripe astringent persimmons, persimmon is a delicious fruit with many positive connotations. In Chinese culture, homophonic puns are woven into everyday life – much more so than in English. In Mandarin Chinese, persimmon, 柿 (shì), is a homonym for thing, 事 (shì). You’ll find plenty of persimmon imagery and wordplay in China – from New Year decorations to gift boxes – because the same sound conveys both a literal fruit and a heartfelt wish that “everything in your life turns out as sweet as a ripe persimmon.” For instance, the blessing 事事如意 (shì shì rú yì), “may everything go according to your wishes,” is often playfully written as 柿柿如意, turning it into a vivid, fruit‑themed, good luck token. So, eat a deliciously sweet persimmon of your choice, and may good things happen to you in the rest of 2025! 2025, 好柿发⽣!

Comment / College rivalry should not become college snobbery30 January 2026

Comment / College rivalry should not become college snobbery30 January 2026 News / Downing Bar dodges college takeover31 January 2026

News / Downing Bar dodges college takeover31 January 2026 News / Cambridge for Palestine hosts sit-in at Sidgwick demanding divestment31 January 2026

News / Cambridge for Palestine hosts sit-in at Sidgwick demanding divestment31 January 2026 Science / Meet the Cambridge physicist who advocates for the humanities30 January 2026

Science / Meet the Cambridge physicist who advocates for the humanities30 January 2026 Features / Are you more yourself at Cambridge or away from it? 27 January 2026

Features / Are you more yourself at Cambridge or away from it? 27 January 2026