From May Week to Vivaldi: is Cambridge’s classical tradition accessible?

Caitlin Newman scrutinises Cambridge’s unique musical culture, and decides whether classical is approachable for students

Cambridge is synonymous with tradition, and musical tradition is no exception. Choral and classical performances are at the heart of every college’s music scene, highlighted by the matriculation concerts the moment you arrive. Beyond the chapel walls, you see posters tied on every fence advertising the many classical concerts in the city, or hear anticipatory chatter about your college’s complines. Even to those less attuned to the genre, Cambridge manages to make its classical tradition sound enthralling.

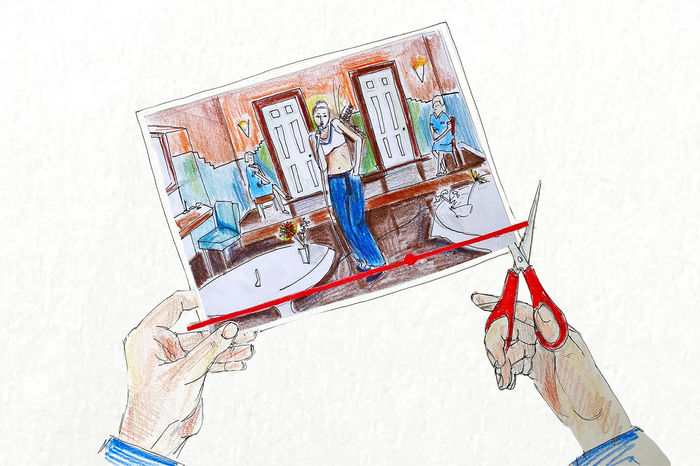

My first experiences with music at Cambridge felt appropriately magical, what with the awe-striking aesthetic decadence of college chapels and the technical perfection of every performer, but I never found myself appreciating it beyond this surface level. A range of factors can be at play when attuning to classical music and trying to ascertain meaning: perhaps a language barrier, stylistic vocal conventions that can obscure lyrics to the untrained ear, or a lack of lyrics entirely. Regardless, I failed to forge any kind of emotional connection with it. The fact that I managed to set the base of my candle alight during my first compline, burning my fingers and getting wax all over my suit, probably didn’t help me forming a positive relationship with classical music either.

“Skipped beats, uniquely placed pauses and the odd jazzy rallentando kept what was a simple motif feeling fresh”

However, a performance of Horovitz’s Sonatina For Clarinet And Piano at my college’s May Week concert triggered a shift in how I view classical music. Unlike my prior experiences, this piece welcomed me with a playfulness. The piano carried a light yet upbeat alto, underscoring the clarinet’s bouncing melody. Simple timing nuances – skipped beats, uniquely placed pauses and the odd jazzy rallentando – kept what was a simple motif feeling fresh. Performed masterfully by Adah Charles and Tingshou Yang, not only with technical skill but with character, I started to grasp how this music, even without lyrical content, could convey emotion. I craved that satisfaction – the moment when the switch flicked and I started to understand the language of the instrumentation without needing the literal word to guide me. A few weeks of summer and a research rabbit-hole later and I was booked to see a performance of Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons at The Underglobe, an intimate venue located underneath Shakespeare’s Globe in London.

Immediately, I was struck by the cosiness of the space. My previously monolithic view of classical music had clearly clouded my judgement. I had envisioned full far-too-many-piece orchestras spread across an intimidatingly oversized stage. Organs mounted to the walls, seas of aloof listeners filling the house; an image akin to the Royal Albert Hall or Southbank Centre. Instead, fairy lights, faux candles, and soft projections lit the room, leading to only ten or so rows of seats.

“Who knew that classical music could have such punk values?”

The performance itself only further reflected the welcoming atmosphere I had felt upon arrival. Before the music commenced, Icon Strings, the London-based string quartet performing the concertos that evening, opened by contextualising each piece. We learned that each season in Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons is accompanied by a sonnet. The English translation of each sonnet was read to us, aiding us in building the image before the music began. The final element of introduction involved demonstrations of how some of the components of Vivaldi’s sonnet were represented in his composition, whether it be soprano lines for birds tweeting or the bass tone of the cello evoking a dog’s bark.

From a modern lens, the Summer concerto felt especially poignant. Instead of the typical summer image of holiday-based celebration and consumption, the mood here was sombre, the weather described as “relentless” and “threatening”. The sonnet talks of climate extremes from the perspective of a farmer struggling to maintain his livelihood in unforgiving conditions; summer’s song is not one of care-free airiness but of palpable tension and despair. Today, the climate is one of many reasons that summer may feel like a threat upon someone rather than a moment of peace – whether your livelihood is at a detriment in summer, your health declines as the heat rises, or even just the fact that this summer has proven to be politically tumultuous for so many of us, this music spoke to that. Who knew that classical music could have such punk values?

I never expected to care so much about the accessibility of classical music (until recently, I had simply resigned it as a genre that was just not meant for me), but giving time to classical music has unveiled a new realm of communication that I wouldn’t have otherwise engaged with. It’s so easy to make this genre accessible too: with a little additional information on the background or construction of a piece, more people can enjoy classical music in a meaningful way. Cambridge is growing increasingly welcoming, slowly learning to cater to the needs of its 93% state school educated cohort. Many Cambridge students go on to be celebrated comedians or sportspeople after having been introduced to these paths by the university. It’s time for Cambridge’s classical tradition to follow suit.

Comment / The (Dys)functions of student politics at Cambridge19 January 2026

Comment / The (Dys)functions of student politics at Cambridge19 January 2026 Arts / Exploring Cambridge’s modernist architecture20 January 2026

Arts / Exploring Cambridge’s modernist architecture20 January 2026 Features / Exploring Cambridge’s past, present, and future18 January 2026

Features / Exploring Cambridge’s past, present, and future18 January 2026 News / Local business in trademark battle with Uni over use of ‘Cambridge’17 January 2026

News / Local business in trademark battle with Uni over use of ‘Cambridge’17 January 2026 News / Your Party protesters rally against US action in Venezuela19 January 2026

News / Your Party protesters rally against US action in Venezuela19 January 2026