Video killed the radio star

Harmony Mitchell assesses the danger of listening to music in snippets

Despite my best efforts, I have once again found myself addicted to Instagram reels. Initially, under the illusion that summer is an infinite expanse of time, the hours scrolling seemed negligible. But this soon soured – my wakeup call occurred when, on a train to London, I overheard a group of teenagers watching TikTok’s at an obnoxious volume. I realised, to my dismay, that I knew most of the clips they were playing by heart.

What’s new about this? Everyone has found themselves humming along to a pop song they’ve unknowingly absorbed through various vague encounters. For years, mediums like radio, MTV, and Top of the Pops acted as cultural transmitters contributing to this centralised base of popular music – picture Kate Bush’s ethereal ‘Wuthering Heights’ music video, or Britney Spears’ iconic snake performance at the VMAs. Yet, today, short form content has altered how songs become part of this popular sphere, and how we as listeners, or consumers, interact with music more broadly. Pop music is now saturated with songs that gained recognition through TikTok, leading to a batch of new (and, to be blunt, vacuous) artists – the likes of sombr, whose music has that certain lifelessness which comes from flattening songwriting into a pursuit of virality.

“Short form content reduces music to decontextualised snippets”

Besides the increased pervasiveness of the earworm, given our repetitive exposure to the catchiest 15 seconds of a track, and the fact that we are now forced to dance to Tiktok songs at clubs and festivals, apps like Tiktok alter the very form in which we encounter music. Unlike mediums like radio, which admittedly also prioritise the attention-grabbing and immediately palatable, short form content reduces music to decontextualised snippets. Cut off from the social conditions of their production – the intentions of the artist, the full-length song/album – clips are recontextualised in new systems of meaning, based on their ability to instantaneously captivate or otherwise communicate some sort of punchline. This allows for songs that lay dormant in the cultural memory to be algorithmically “revived” – think the recent resurgence of the six-decade-old track ‘Pretty Little Baby’. The implication of this, however, is that songs as harrowing as Kate Bush’s ‘Army Dreamers,’ which muses on the tragedy of war, become mere backdrops for so-called “dark fantasy” or “cottagecore” edits.

“TikTok cannot account for rhetorical devices like sarcasm which become incoherent when severed from their context”

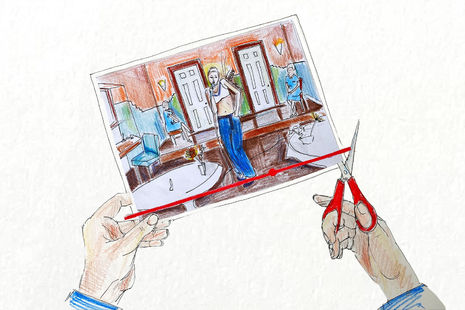

This snippet format, then, leaves tracks susceptible to being reconfigured for questionable ends – consider No Doubt’s ‘Just a Girl’ and its accompanying video. The track explores the imposed emotional and physical servitude of femininity, with the hook ‘I’m just a girl’ sarcastically epitomising both hopelessness and resistance in the face of this. On TikTok, however, the song has been dismembered beyond recognition, with the line ‘I’m just a girl’ becoming a slogan for women to relay their experiences of being ditsy, frivolous, bad at driving, among other gendered stereotypes. There is complete indifference here to Stefani’s lyrical intention – she is, in fact, rejecting this reduction of women to ‘just’ girls. While the impact of art will always exceed artistic intent, this seems less a matter of audience interpretation and more that the form music assumes on TikTok cannot account for rhetorical devices like sarcasm which become incoherent when severed from their context.

This way of consuming music is embedded within the logic that music is something to be consumed, content rather than an emotionally evocative, challenging, and sometimes even tedious experience. Music becomes a matter of pure sensory input, something the individual consumes in a vacuum, compared to, say, a gig, where the sensation of a crowded room, the overbearing thumping of the bass amp, creates an entirely immersive experience that is inextricable from its social aspect.

“There is no anticipation of a social interaction besides perhaps a like of approval”

But this pathology is not limited to digital mediums – though records leave songs firmly contextualised in the form of the album, analog music is not inherently richer. As someone who collects records and has dabbled in the most pretentious of music mediums (the mixtape phase), most of the listening experiences that have been significant to me have been digital. Things like sharing songs through phone speakers, or being fifteen and listening to the Juno soundtrack every morning on my walk to school.

Likewise, buying analog is a consumptive practice which is not immune from the neoliberal phenomenon of commodities being treated as formative of individual identity. We can think of the “performative man” trope, armed with Clairo on vinyl and an urban outfitters Crosley Cruiser. While this stereotype is largely playful, it reacts to this contemporary idea that the music one consumes correlates to who one “is,” that taste is a means of individual differentiation. This diverges from subcultural models of identity, whereby music is embedded into group allegiances. Consider the centrality of artists like Siouxsie and the Banshees or Joy Division to 1970s goths, groups also bound by fashion and political sentiments. Alternatively, when I post a Siouxsie Sioux song on my Instagram story, the action is limited to reflecting something about myself and my music taste – there is no anticipation of a social interaction besides perhaps a like of approval.

Ultimately, then, whether in digital or analog formats, music is cheapened when it is a pursuit solely of the individual. It is miserable to perceive music as an identity signifier through which you must differentiate yourself, just like it is insufficient to treat music as an atomised auditory experience, separate from any cultural or contextual relevance.

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026 News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026 News / University Council rescinds University Centre membership20 February 2026

News / University Council rescinds University Centre membership20 February 2026 News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026

News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026 News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026

News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026