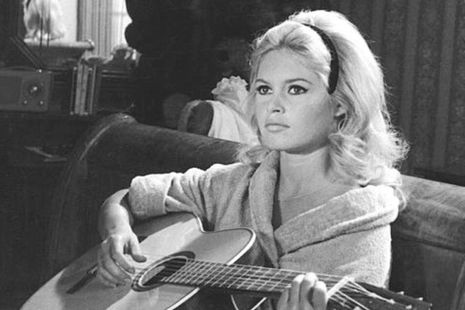

The beauty and bigotry of Brigitte Bardot

Ruby Redwood traces the perplexing arc of the film star, exploring how the ultimate screen siren morphed into a mouthpiece for intolerance

The Brigitte Bardot image is a panorama that cannot be viewed wholly, no matter how many steps back its viewer may take in an attempt to understand it. The image is one of an iconic film star from the 1960s: a ‘sex kitten’ sold to audiences of drooling men and blushing women. Many others and I held this picture in the periphery until the day of her death last month, when we turned our eyes towards it and realised its irregularities. Bardot was (as the flood of journalism on her in light of her recent death reveals) a complex person associated with sex, hate, love and hate again; a woman whose influence may be classified as sinister, but was absolutely undeniable.

Brigitte Bardot was born to prosperous Parisien Catholic parents in 1934. However, from the beginning, her upbringing was marred by violence. She possessed a volatile resentment of her restrictive and abusive household, frequently rebelling, and once even attempting suicide as a response to her father’s objection to her relationship with her “wild wolf”, director Roger Vadim. Amidst such family chaos, fame also struck her from young, thrusting her into the limelight. She began modelling at age 15, and soon after made her first appearances in films such as Crazy for Love (1952) and Act of Love (1953).

Vadim’s melodrama And God Created Woman (1956) was when her popularity skyrocketed, playing the role of an immodest teenage flirt which amazed cinemas full of sexually repressed Americans. Over the late 1950s and 60s, Bardot starred in several successful films, including Babette Goes to War (1959), The Truth (1960) and Godard’s new-wave classic Contempt (1963). During her time as an actress, she also enjoyed a lucrative musical career, often collaborating with singer Serge Gainsbourg. In 1969, she even became the official face of ‘Marianne’, the personified symbol of the French Republic since the French revolution, a concrete manifestation of her significance to French patriotism and cultural identity. She announced her retirement after the film Don Juan, Or If Don Juan Were A Woman (1973), attempting to exit the industry, in her own words, “elegantly”.

“Modern feminism regards Bardot with ambivalence”

She was known for her entrancing sensuality, becoming an icon of the sexual revolution. For many women, Bardot represented (in Simone De Beauvoir’s words) “absolute freedom” – her performances were a celebration of female physicality, a symbol of shameless independence and the liberation of women leading up to the second wave feminist movements of the 1960s and 70s. Bardot was not a feminist, though, and many of her roles, despite being sexually empowering, still relied heavily on the leering male gazes of her co-stars, reducing her to a patriarchal caricature of a woman – beautiful, incomprehensible, and foolish. Modern feminism regards Bardot with ambivalence; her influence to the sexual revolution is beyond doubt, however, many of her characters remain misogynistic and are fundamentally hurtful when seen today.

After her departure from the Silver Screen, a transition in Bardot’s focus was instantly recognisable. From the late 1970s onwards, Bardot dedicated herself to the pursuit of animal welfare, becoming a vegetarian and even selling personal items to fund the creation of the Brigitte Bardot Foundation in 1986, famously stating: “I gave my beauty and my youth to men, I’m going to give my wisdom and experience to animals.” Her campaigning stretched from support for the adoption of stray dogs in Romania to opposition of the consumption of horse meat and the strategic culling of cats in Australia.

“[A] cigarette-smoking symbol of French identity with enough blazing sexuality to melt the Eiffel tower”

However, in her later years, Bardot’s compassion for animals became somewhat confusing when set against her controversial and offensive political opinions. She took aim at many minorities and oppressed communities, calling gay people “fairground freaks”, inhabitants of the island Réunion “savage”, women involved with the #MeToo movement “ridiculous”, and frequently insisting that the Islamic population of France was threatening traditional French society and values. These statements did not only provoke raised eyebrows, but they also caused Bardot to be fined multiple times by the French court for charges related to racial hatred. These less-than-empathetic aspects of Bardot’s personality were also manifest in her close relationships, particularly between her and her son, Nicolas-Jacques Charrier. Writing in a 1996 memoir, she compared her unborn son to a “tumour” and stated she would “rather have given birth to a little dog”. Their relationship remained strained, with Charrier and his father later suing Bardot for the hurtful comments she had made.

Bardot was a complex woman. She will remain a hugely influential and iconic figure in European cinema well into the future – a cigarette-smoking symbol of French identity with enough blazing sexuality to melt the Eiffel tower. But, the Bardot patriotic vim harnessed in her later life that was the cause of some much harm and hurt, means that her legacy should not remain stain free. However, our instinctive urge to reconcile these oppositions within her is futile. Instead, we can only accept that the Bardot legacy will remain stubbornly challenging, just like Bardot herself.

News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026

News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026 News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026

News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026 Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026

Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026 News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026 News / King’s faces backlash over formal ticket policy 7 March 2026

News / King’s faces backlash over formal ticket policy 7 March 2026