Anticipating Christopher Nolan’s The Odyssey

Mia Badby looks to the current state of Hollywood to predict how epics may now fare onscreen

Like most people who have read and studied The Odyssey, I watched the trailer for Christopher Nolan’s upcoming adaptation through my fingers with a mix of dread and excitement. From the announcement that Nolan’s follow-up to the wildly successful Oppenheimer (2023) would be an adaptation of the classic Greek epic, my heart sank a little. This isn’t going to be a complaint about the casting choices – I doubt anyone wants to read my whinging about Matt Damon as Odysseus or Tom Holland as Telemachus. Rather, it will be a judgement on how the current climate of Hollywood will shape the execution of the film, and what we can expect to see and not see in Nolan’s audacious epic.

The immense scale and breadth of the undertaking raises the question: has the historical epic had its heyday? Could The Odyssey be a revival of the stagnant genre, or perhaps begin a new direction for Hollywood, away from remakes of beloved classics, and into the works of classical antiquity? The question of a historical epic revival has been in the air for some time now: Ridley Scott’s Gladiator 2 (2024) revived some hope for such a resurgence, but the lack-luster response to the film all but snuffed out the potential. Perhaps Hollywood has an A-list addiction that has sickened the appetite of the viewing public. Yes, big names draw in big numbers, but at the expense of immersion – a flaw which I am coining the 1917 effect. The war drama was an odyssey in itself, using big name actors as post-markers for the narrative; this was indeed clever in theory, but it became almost ridiculous to arrive at the climax only to be greeted by Benedict Cumberbatch. Bathos is a killer, so be warned.

An unknown (or relatively unknown/underrated) casting choice could be the difference between immersion and alienation. This is what the original Gladiator got right: striking a balance between the up-and-coming Russell Crowe and Joaquin Phoenix, and the titans of acting (on screen and stage) Oliver Reed and Richard Harris. Perhaps this effect was attainable in part because Hollywood was still held at an arm’s length, with the internet in its infancy and the industry still elusive yet lauded; our current age of accessibility and abundant Vanity Fair press junkets has the tendency to take the illusion and mystique out of an actor’s performance. Be that as it may, Nolan’s famously methodical, almost compulsive attention to detail and accuracy makes his period films watertight, and yet, in my opinion, he is ultimately let down by his casting choices. Watching Oppenheimer with any knowledge of the current cinematic landscape was a combination of unbridled awe and confusion as we trundled from scene to scene, collecting A-listers like Pokemon Cards. I can’t be the only one who was completely taken out of the climactic nuclear test scene when Josh Peck, of the eponymous Nickelodeon masterwork Drake and Josh, popped up on screen.

“An unknown (or relatively unknown or underrated) casting choice could be the difference between immersion and alienation”

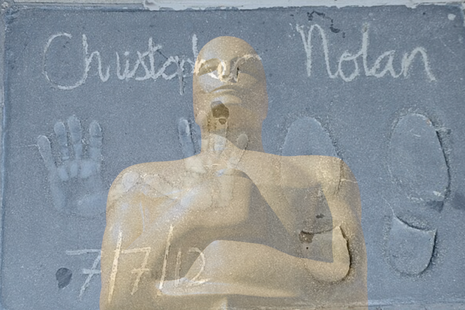

Of course, another successful ensemble epic is Denis Villeneuve’s Dune franchise, its third installment already highly anticipated due to the success of its first two entries. This could very easily divulge into a love letter to Villeneuve and what he is doing for cinema, but regardless, both he and Nolan represent a kind of Leviathan style of filmmaking that is dedicated to detail, immersion, and, most crucially, long runtimes. Interesting here is that both the Dune films and indeed The Odyssey are the culminations of the directors’ life-long dreams: Villeneuve has had the project in mind since reading Frank Herbert’s novels as a teenager, while Nolan is now at the stage in his career (no doubt thanks to the golden statuette on his mantelpiece) where he can pull off what could be the greatest passion project to ever hit the mainstream.

The rhythm of The Odyssey has the potential for some truly innovative film-making: the recurring refrains, for instance, beg for musical interpretation. I have faith in Ludwig Göransson to produce a fresh and robust soundtrack that will carry the film through its epic course. Leitmotifs are obviously nothing new, but I would like to see Göransson push them to their limits and re-invent the wheel, so to speak.

My forecast is as follows: we can expect to see treacherous storms and perilous encounters with the Cyclops, the man-eating giants, Circe, Scylla and Charybdis, and a sweeping display of the spatial multitudes within The Odyssey (I am particularly looking forward to the Underworld sequence). We must, however, bear in mind that while there is great stylistic and cinematographic potential for the various lands Odysseus and his crew encounter, we can’t exactly have our cake and eat it too: perhaps the full-scale epic is too immense for our contemporary palette, such that, in attempting to balance the duality of one man’s whirlwind journey (literally) to Hell and back to get home and a domestic drama, the crucial nuances of Homer’s epic will get lost along the way.

Nuances such as xenia (hospitality) and kleos (glory) are integral to the choices made by each character. This, unfortunately, would require some quite clunky exposition, or perhaps a motif (auditory or visual). Furthermore, in light of some responses to the recent Marty Supreme, it seems that we as a viewing audience have forgotten the allure of the anti-hero. Heroes aren’t meant to make all the good or right choices, otherwise we would be bored to tears. Odysseus is by no means an anti-hero, but Homer imbues his character with remarkable moral ambiguity: the conflict between his own interests and the interest of his crew drives the action of the homecoming narrative. It will be a bitter pill to swallow for some, in light of Odysseus’ dubious decision making and uncompromising heroic principles. Likewise, early reactions to stylistic choices in The Odyssey’s trailer, namely the discourse surrounding the design of Benny Safdie’s Agamemnon (his historically inaccurate helmet boasting a spinal detail at the nape), suggest that the film could have benefited from the “Wuthering Heights” treatment of putting the title in quotation marks, denoting an interpretation, rather than a by-the-books adaptation. The license of the epic, however, is that it bridges the real and the surreal in its wars, domestic unrest, and homecomings, against its gods, monsters, and magic. Some creative liberty is welcome for thematic and characterological effect, but directors must walk that line carefully, lest they venture into the absurd.

"Some creative liberty is welcome for thematic and characterological effect, but directors must walk that line carefully, lest they venture into the absurd”

So, classicists, abandon all hope, ye who enter. Your arms will only tire from holding your pitchforks and torches for so long, so accept the disappointment of historical accuracy now and approach the film with as open a mind as possible. We can only hope that Nolan will attempt to capture the visionary power of imagination, when we read The Odyssey for the first time and saw a film play out in our heads, inaccurate yet evocative, a lucid impression of mythology made real. But I think we can all agree that if Nolan omits the reunion with Argus the dog, then the film is a complete and utter failure.

News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026

News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026 News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026

News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026 Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026

Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026 News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026 News / King’s faces backlash over formal ticket policy 7 March 2026

News / King’s faces backlash over formal ticket policy 7 March 2026