Reality wins more Oscars than fiction

Naviya Gupta questions the ethics of our obsession with biopics

Among the most interesting things I have seen is a photograph of Jackie Kennedy and a flower bouquet from 1969. Unsurprisingly, she’s in New York: on some glamorous street in a glamorous neighbourhood with the glimpse of a glamorous car in the background. You can barely see her face — the flowers she’s holding are held up high enough to conceal it. Yet, from the light trench coat to the sunglasses perched elegantly on her not-a-strand-out-of-place hair, it is unmistakably, undeniably her: the former First Lady of the United States, forever captured in motion with somewhere important to be.

Like much of the handiwork of the ancient paparazzi, to photograph the Very Famous Person, they catch the persona instead: a carefully constructed image inhabited for the cameras and premieres, where smiles don’t falter and the right things are always said. How romantic the mystique of these shiny, beautiful, successful people whose names everyone knows and whose music is in everyone’s head. How powerful and infuriating.

“There’s a fundamentally human flaw in our complete inability to mind our own business”

There’s a fundamentally human flaw in our complete inability to mind our own business. I believe this fault is best reflected in our invention and use of the internet. Being famous in the digital age is a whole other skillset — doing brand deals, tweeting the right things and reposting movie trailers for nepo babies trying to break into the industry. Today’s celebrities seem to have gotten a collective memo: Your art isn’t enough; the world is entitled to your time, your personhood, your lives, too. Interestingly, filmmakers seem to have decided that the celebrities of yore don’t get a free pass, either.

Every month, as a new one-word title hits the box office (think: Oppenheimer (2023), Elvis (2022), and unsurprisingly, Priscilla (2023)) I leave dazzled by award-season-sweeping performances and cinematography that surpasses my eyesight. However, I can’t help but feel unnerved by how the life of a real person was rearranged and rewritten, with traumatising life events played out by crying actors backed by dialect coaches, cut for time, and finally sold to a world of riveted audiences. “What would shock them?” I hear the director think, “who shall we cast as the Alcoholic Father?” Any ghost of mystique, much less a persona, has been obliterated, and yet another story joins the ranks of the oversaturated void of information that is the internet.

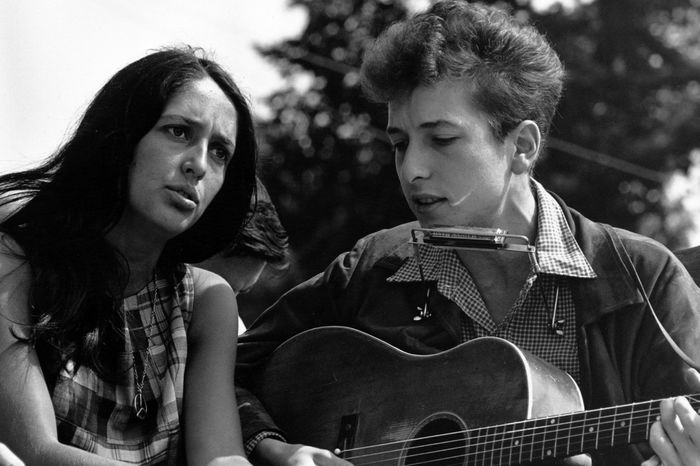

Like every other person on Earth, I too, saw that clip of Timothée Chalamet’s SAG acceptance speech, and then proceeded to watch A Complete Unknown (2024) with no expectations but that of Timothée’s performance. My first and only introduction to Bob Dylan’s music was when he won the Nobel Prize for Literature 2016 and I downloaded ‘Blowin' in the Wind’ on iTunes. I knew he wrote lyrics that were so good they won a literature award, and that he helped the American protest movement. From this perspective, the film served as a medium for me to learn more about an important figure in history about whom my knowledge was perfunctory at best. Like most modern films with star-studded casts and budgets, it was objectively good, with Dylan himself apparently being heavily involved in its production. People should be allowed power over their narrative, but it’s unlikely that an already highly successful and acclaimed artist of Dylan’s demographic would experience a lack of it.

“The world is entitled to your time, your personhood, your lives, too”

The problem lies when someone’s story is taken out of their hands and placed into those of people seeking to profit off of it — when a name is used to present a changed narrative for the world to see and form opinions about. The controversy surrounding the casting of Zoe Saldana in Nina (2016), based on the life of the late Nina Simone was particularly uncomfortable — as the artist herself could not have a voice in how her story was told. However, her representatives expressed objections with the casting, following which the film proceeded regardless of the disagreement. This begs the question: don’t we have a duty to those who have passed to preserve their memory with respect and dignity?

Being tasked with telling someone’s story is a very special privilege — it can do immense damage when done ignorantly, but I also believe it can do good when done with both the best of intentions and careful execution. Like most art, I believe that the viewer, too, has a responsibility to consume media with a critical eye: perceiving these films as an interesting way to learn more about exceptional people and their contributions to the world while also letting oneself be entertained and taking it all with a pinch of salt.

Want to share your thoughts on this article? Send us a letter to letters@varsity.co.uk or by using this form.

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026 News / Gov grants £36m to Cambridge supercomputer17 February 2026

News / Gov grants £36m to Cambridge supercomputer17 February 2026 News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026 News / CUCA members attend Reform rally in London20 February 2026

News / CUCA members attend Reform rally in London20 February 2026 News / Union speakers condemn ‘hateful’ Katie Hopkins speech14 February 2026

News / Union speakers condemn ‘hateful’ Katie Hopkins speech14 February 2026