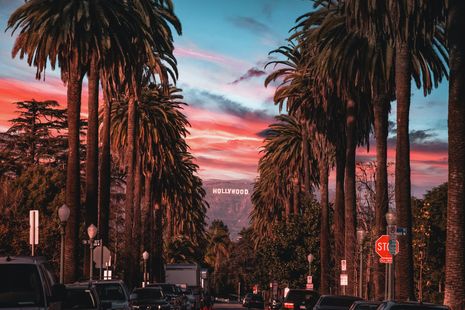

Damien Chazelle’s uproarious ode to Golden Age Hollywood

The Oscars’ youngest Best Director winner to date returns to the big screen with this ill-disciplined but unwaveringly watchable Tinseltown fable

It’s an adage as old as storytelling itself that you must capture the attention of your audience within minutes if you want them to carry on listening. “Call me Ishamel”; “It was a bright cold day in April, and the clocks were striking thirteen”; “Rosebud”; there’s nothing with quite as much power to draw us in as a caustic opening line.

I may not remember the exact first words of Babylon, but let’s address the elephant in the room. Or, rather, the very literal elephant in the truck that, within the first five minutes of Damien Chazelle’s divisive new film, projectile defecates right into the camera. Consider our attention captured. This moment suitably encapsulates Babylon’s unflinching audacity, its warts and all, equal parts loving and loathing portrait of the American film industry in its sleaziest era. Indeed, it’s an era so sleazy that the sight of a defecating elephant at a party soon looks relatively tame.

Following in the sprawling footsteps of such sun-soaked Los Angeles epics as Paul Thomas Anderson’s Boogie Nights and Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon A Time... in Hollywood, Babylon sees Chazelle take all of his characteristic impulses, and dial them up to their greatest extremes. The milieu is familiar, as we follow Hollywood through its turbulent first half century: the shifts from silent films to the talkies, from cinema as embryonic art form to economic juggernaut. It’s a world we navigate through various eyes, most notably abrasive starlet Nellie LaRoy (Margot Robbie), charming has-been Jack Conrad (Brad Pitt), and eager Hollywood wannabe Manny Torres (Diego Calva).

“It’s no mean feat trying to refigure the entire history of cinema into one outrageous, bacchanalian collage”

Clocking in at a little over three hours, Babylon is highly ambitious — perhaps slightly to its own detriment. With intertextual references abound to the iconography of classic Hollywood, the film feels like watching Chazelle wrestle with a wild beast he might lose control over at any moment. It’s no mean feat trying to refigure the entire history of cinema into one outrageous, bacchanalian collage; think Singin’ in the Rain on cocaine. Not every idea lands — but that’s less of a problem when you’re throwing around fourteen of them at the screen at any given moment.

Continuing a strong track record for Chazelle’s films, the performances in Babylon are committed across the board. As Nellie, Robbie echoes her breakout role in The Wolf of Wall Street; complete with a thick New Jersey accent, it’s a showy turn, but one that feels neatly attuned to the film’s sensibilities. A more restrained Brad Pitt lends his role a well-judged melancholic air that cuts through some of the film’s louder moments. If Calva’s Manny feels comparatively less fully-formed, it’s never a reflection on the actor himself, who delivers a sensitive and likeable performance.

While the film has perhaps unexpectedly failed to materialise its initial awards hopes in major categories, its below-the-line nominations are well-deserved. Florencia Martin’s production design bursts with painstaking period detail and Justin Hurwitz, a long-time collaborator of Chazelle’s, offers a pulsating, jazz-inflected score. I challenge you to listen to the track “Voodoo Mama” without getting the tune immediately stuck in your head.

“Its warts and all, equal parts loving and loathing portrait of the American film industry in its sleaziest era”

Even if the relentless debauchery occasionally borders on exhausting, this is tempered by more muted, but no less striking moments that offer a welcome change of pace. “It’s been over for a long time”, Jean Smart says in a perfectly pitched monologue, as her haughty gossip columnist offers Pitt’s character some harsh home truths about an industry that no longer wants him. Jovan Adepo, sorely underused as a Sidney Easton-esque trumpeter, bristles with silent fury as he is forced to wear blackface, in order to match the skin tones of his backing band.

Scenes like these (which the film could use more of) reveal the unsettling substance behind Babylon’s flashy style. It’s ironic that Chazelle returns, perhaps more than any other work, to Singin’ in the Rain, that quintessential romantic vision of Hollywood’s ‘Golden Age,’ when the outlook of his own film couldn’t be more different. There are few opportunities for happy endings in a world in which the movie-making machine ruthlessly gobbles up everything and everyone around it, only to, in the fashion of our old friend the elephant, promptly shit them back out again.

So, as the film ends with a character staring up at a cinema screen with tears in their eyes, we’re left with a judgment to make. Might they be tears of gratitude, of cinephilic rapture? Perhaps — but I found myself wondering whether they might instead be cries of despair.

Interviews / Lord Leggatt on becoming a Supreme Court Justice21 January 2026

Interviews / Lord Leggatt on becoming a Supreme Court Justice21 January 2026 Features / Are you more yourself at Cambridge or away from it? 27 January 2026

Features / Are you more yourself at Cambridge or away from it? 27 January 2026 News / Reform candidate retracts claim of being Cambridge alum 26 January 2026

News / Reform candidate retracts claim of being Cambridge alum 26 January 2026 News / Report suggests Cambridge the hardest place to get a first in the country23 January 2026

News / Report suggests Cambridge the hardest place to get a first in the country23 January 2026 News / Cambridge psychologist to co-lead study on the impact of social media on adolescent mental health26 January 2026

News / Cambridge psychologist to co-lead study on the impact of social media on adolescent mental health26 January 2026