Agnes Varda’s use of film as memoir

Enchanted by the works of a genius, Madeleine Pulman-Jones takes this year’s recipient of the Honorary Academy Award as her latest subject

“I’m playing the role of a little old lady, pleasantly plump and talkative, who is telling the story of her life.”

So says iconoclastic filmmaker Agnès Varda at the beginning of her 2009 autobiographical documentary, The Beaches of Agnès, but as the humorously ironic line knowingly points out, Varda is so much more than an eccentric old lady. As she says the line, she is walking slowly backward on a beach, barefoot. She is draped in a combination of knitwear and flowing mauve fabrics, sporting her iconic monk-style haircut which is now white at the centre with a ring of purple at the ends.

Varda proposes that “if you opened people up, you would find landscapes. If you opened me up, you would find beaches.” Thus she establishes the premise for her autobiographical documentary. Beaches have been the dominating landscape in her life – from the beaches of Belgian summer holidays in childhood, to teenage escapades in the south of France, to the beaches next to the summer house she owned with her husband Jacques Demy. As the title and Varda’s reputation would suggest, the film is so much more than a conventional documentary. The result is revelatory – a beautiful, profoundly poetic meditation on life and art which is as often melancholy as it is eccentrically funny.

“The oddball playfulness and joi de vivre is countered by side by a reflective melancholy in Beaches”

Arguably all of Varda’s films are to an extent autobiographical. Through both her fiction and non-fiction, Varda has pioneered a deeply personal cinema which is almost undefinable. From a feminist standpoint, female-directed autobiographical cinema is revolutionary in providing an alternative to the historical patriarchal documentation of women’s lives. Though her non-fiction work has been highly acclaimed, it is Varda’s feminist fiction works for which she is best known, such as Cléo from 5 to 7 (1961), Le Bonheur (1965), and Vagabond (1985), but Varda has also pioneered an exciting form of cinema which lies somewhere between the cine-essay, poetic fiction and documentary. Varda’s decidedly unconventional autobiography, the definitive example being The Beaches of Agnès, is just as much a genre-bending exercise in auteur cinema as it is a feminist statement about female authorship.

Agnès Varda was born in Ixelles in Belgium in 1928 to a Greek father and a French mother. During WWII, Agnès moved with her family to Paris where, apart from a short period in California, she has lived and worked ever since. After studying art history at L’école du Louvre, Varda turned her attentions to photography. While her portraits garnered attention, including from Henri Cartier-Bresson, Varda was unsatisfied with the form. In Beaches, she describes a desire to put words to her images. Later, she notes, she discovered that cinema was so much more than this.

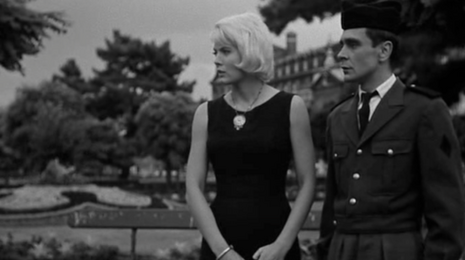

After her revolutionary debut, La Pointe Courte (1955), which featured all the hallmarks of Nouvelle Vague five years before its true beginning, Varda returned for a time to photography, travelling to China alone in 1957 to document the new People’s Republic. After her 1961 film Cléo from 5 to 7, her position at the forefront of avant-garde cinema was cemented. After the nouvelle vague, she made political films such as Une Chante L’autre Pas (1972) and a documentary short on the Black Panther movement, and has recently moved toward documentary and installation art. She was awarded an honorary Palme d’Or at Cannes in 2015, and an honorary Academy Award in 2017.

Expertly weaving surrealism, metaphor, poetry, memoir and archive footage, The Beaches of Agnès is perhaps closer to the French literary genre “autofiction” than to conventional documentary autobiography. Indeed, Varda herself refers to her cinema as cinécriture, merging the words “écriture” (writing) and “cinéma” to define her distinct cinematic practice. It is a type of cinema with which Varda has been toying for years in films such as Oncle Yanco (1967) and Documenteur (1981), but the ambitiousness of The Beaches of Agnès is beyond any of her previous autobiographical works.

Varda constructs the film like a collage, or perhaps a modernist novel. From a beach covered in antique mirrors which reflect passing faces and the camera itself, to a nude recreation of Magritte’s ‘The Lovers,’ to a full-size whale sculpture inside which Varda sits, to a robot-voiced cartoon cat, to a makeshift beach in the middle of Paris, the vividness and tangibility of the realisation of Varda’s life and creativity is staggering.

The oddball playfulness and joi de vivre is countered by side by a reflective melancholy in Beaches that one rarely encounters in autobiography, cinematic or literary. At its centre is Varda’s love and mourning for Demy. Another filmmaker of the Nouvelle Vague, Demy mainly made musicals which often starred Catherine Deneuve and were almost always scored by jazz legend Michel Legrand, such as Les Parapluies de Cherbourg (1964) and Les Demoiselles de Rochefort (1967), which too combined bright colours and wacky humour with unsettling elements.

Varda has said that, “to love cinema is to love Jacques Demy, painting, family, and puzzles… and again to love Jacques Demy, for a long time, until the end.” Demy tragically died of AIDS in 1990, and Varda describes her grief in Beaches: “emotion is something you can’t control. Naturally I think of Jacques. All the dead lead me back to Jacques. Ever tear, every flower, every rose and begonia, is a flower for Jacques. He’s the most beloved of the dead.” Varda describes his last months vividly, during which she made Jacquot de Nantes (1990), a film about Demy’s childhood.

Despite Varda’s hardships, her final lines, sitting in a glass cabin she constructed using the film reels of The Creatures (1966) in a gallery, are as follows: “What is cinema? Light coming in from somewhere, captured by colours more or less dark or colourful. When I’m here, I feel as though I live in cinema - that it’s my house. I feel as though I’ve always lived there.” Varda’s autobiographical works are testament to this comfort – a comfort not only in cinema, but in breaking the rules

News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025

News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025 Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025 News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025

News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025 News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025

News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025 Fashion / The art of the formal outfit 18 December 2025

Fashion / The art of the formal outfit 18 December 2025