Sharing spaces with statues

Mia Apfel reflects upon the ways college statues interact with their environments

After being granted a five-minute escape from the stuffy room of my supervision one hazy afternoon last week, I found myself wandering the courts of Christ’s College. Although I assumed solitude, once settled in a secluded spot I was not unaccompanied. Charles Darwin, life-sized and familiarly human, sat beside me. Perched on the wooden arm of my undisturbed bench, his bronze form glistened under the heat of the midday sun. Scorching to the touch, there was something unsettlingly intimate about the accessibility of interaction with this statue of the renowned biologist, seemingly so distant a figure as the father of evolution.

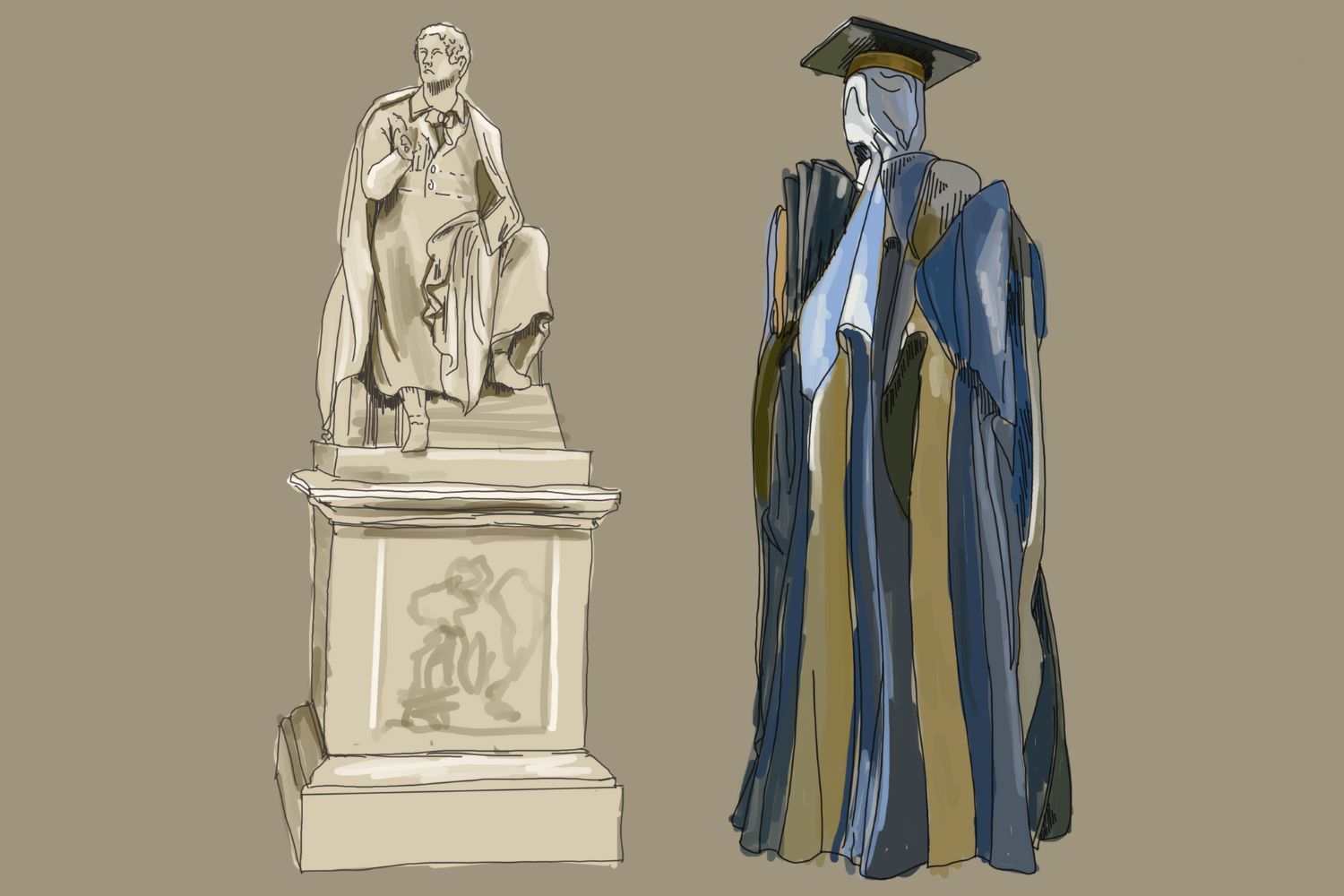

Depicting Darwin as a young man, roughly the age at which he studied at Christ’s from 1827 to 1836, the statue was commissioned by the college in 2009 and sculpted by Antony Smith. Darwin’s scholarly posture sees him staring out with a contemplative look in his eye, perhaps capturing the very moments of the biologist mid-muse, resolutely working through evolutionary dilemmas.

He is unrecognisable as the heavily bearded Darwin: the erudite scientist who comes to one’s mind. Instead, Darwin’s youthful face is almost mistakable for the face of a juvenile undergraduate who might, like me, happen upon this scene during a break from their studies. His outfit, of a waistcoat and bowtie, dress shoes and tailored overcoat gives him away as a student of the past, however – incongruous with the modern-day library attire of pyjamas and slippers. Books haphazardly set down on the bench, the bronze accessories of the figure further integrate him with his environment. Students of the college are invited to place their own books down next to Darwin’s, to rest with him for a moment in this contemplative setting.

The 40th issue of Christ’s’ Pieces newspaper exhibits an image of Smith’s Darwin statue on the front cover. A humorous addition, however, is that of a Christ’s-branded face mask arranged on the statue, a reminder of the deep wade into the Covid pandemic which was being grappled with at the time of this issue’s publication. This statue, then, whilst commemorating a figure of the distant past, is capable of being brought into the present. Darwin, in his bronze form, can interact not only with the physical environment of a college garden, but with the current and continually changing events of a society whose existence has surpassed his death 143 years ago, in 1882.

“Students of the college are invited to place their own books down next to Darwin’s, to rest with him for a moment in this contemplative setting”

Darwin’s is not the only statue which assimilates itself with its college habitat. At St. Edmund’s, the statue of St. Edmund of Abingdon himself acts likewise. In a similar bronze silhouette, the 13th century Archbishop of Canterbury sits poised in thought and hunched over a book open on his lap. Nevertheless, there is, I would suggest, something distinctly less intimate about this statue. Perhaps this distance between statue and student is rooted in the fact that, it is not possible to breathe life into this thirteenth century figure with historical accuracy, as Edmund’s sculptor Rodney Munday noted. We cannot possibly know what he would have looked like.

However, there is still room to bridge the gap between statue and student, Munday insists. Whilst we cannot draw a representation of St Edmund based on knowledge of his physical appearance, we can use knowledge of his personality to animate him. Munday writes on his website about his creation of a life-sized version of Edmund, suggesting this stylistic choice to allow the statue to “blend in with and in a sense be lost amongst the people who would come to surround him”.

“Edward’s dwelling place outside of the college chapel allows him to interact with 21st century students, and to become a participant in the events of their epoch as well as his own”

Munday claims that to represent Edmund as a familiar figure is fitting with what personality of his we can gage from historical records, which suggest him to be a man “who avoided the trappings of authority” and “was regarded as friendly and helpful to others, despite huge personal austerity”. Munday’s task, arguably more challenging than that of Smith’s, sees him out of bronze material mould “a considerate yet strong personality within a body wasted away by extreme asceticism”.

Not unlike Darwin’s statue, Edmund’s dwelling place outside of the college chapel allows him to interact with 21st century students, and to become a participant in the events of their epoch as well as his own. One occasion a few years ago clearly demonstrates this. As was reported in a 2023 Varsity article, the statue was subject to an act from students who “plastered” it with coloured powder in celebration of the Hindu festival.

College statues also communicate with the natural changes of environment which Cambridge experiences throughout the seasonal year. Edmund’s book becomes heaped with snowfall in the winter, and his hand which gently rests on the stone bench trapped under the frosty blanket. In summer, Darwin warms, thawing under the faint rays of the timid English sun.

These statues, enduring throughout time, yet still seemingly subject to yearly or even monthly changes, I have found to provide a surprising sense of comfort. The ability for an inanimate mass of metal to metamorphose into a human-form offers a welcoming familiarity for a college. Grand figures of history rest on benches mid-thought, just like any other student of this well-chronicled environment.

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026 News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026 News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026

News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026 News / CUCA members attend Reform rally in London20 February 2026

News / CUCA members attend Reform rally in London20 February 2026 News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026

News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026