How does the brain become conscious of its thoughts?

Nessa Yip explains the progress made by neuroscience towards answering a question at the centre of the human experience

I’ve got your attention now. As your eyes follow my words, are you still picking up on the low hum in the background? What are you consciously perceiving in this moment?

Understanding the nature of consciousness has historically been the activity of the philosopher, but humanity’s unyielding interest in the matter paved the way for neuroscience to take off. While big questions in neuroscience remain unanswered, not least questions regarding consciousness, there have been fascinating attempts to understand it.

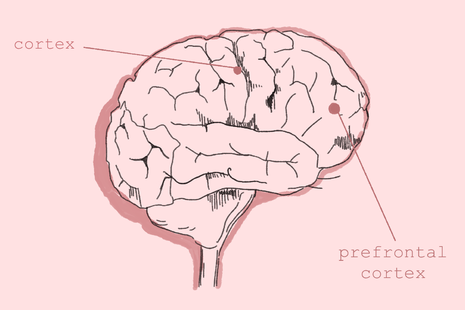

In a recent study, Mingsha Zhang and his colleagues at Beijing Normal University set off to investigate how our brains become aware of our own thoughts, a phenomenon termed ‘conscious perception’. Neuroscience dogmatically attributes consciousness to structures in the cortex: the folded layer of the brain we often associate with images of the brain. While deeper ‘subcortical’ structures are known to contribute to cognitive functions such as sensory perception or motor function, their roles in higher consciousness are generally deemed secondary to the cortex in mainstream neuroscience.

“Researchers proposed that the thalamus acts as a ‘gate’”

One such subcortical structure is the thalamus (albeit an esoteric-sounding thing to the non-scientist, believe me, it’s a BNOC – a big name in cognitive neuroscience…) which sits in the centre of the brain. Some regard the thalamus as a mere ‘traffic controller’ for the cortex, integrating sensory inputs and directing information flow. In contrast, some propose the thalamus has a higher role and contributes to conscious perception, despite a lack of studies involving humans as research participants. There is a subtle difference between the two: the latter school hypothesises that the thalamus’ role extends beyond sensory processing and includes the emergence of consciousness.

In their study published in Science, Zhang and his team studied patients who had electrodes inserted deep into their brains as part of an ongoing treatment. Their method (stereoelectroencephalography) allowed simultaneous recording from two different regions of the brain: the thalamus and the prefrontal cortex, a cortical region strongly linked to higher executive functions such as decision-making. The participants were shown images with the contrast designed so that these images would not be detected half of the time. They then reported whenever they became aware of the image.

Significantly different results in both regions of the brain were collected when the participant was conscious of the image compared to when they were not. Interestingly, two areas of the thalamus (the intralaminar nuclei and the medial nuclei) demonstrated earlier and larger activity compared to the prefrontal cortex. The researchers proposed that the thalamus acts as a ‘gate’, parsing sensory information and relaying relevant bits to the prefrontal cortex. This effectively ‘tells’ the brain which thoughts to be aware of, which the researchers argued was evidence for thalamic involvement in conscious perception.

“Perhaps both views of the thalamus are compatible?”

So, perhaps both views of the thalamus are compatible? Perhaps the ‘traffic controller’ role of the thalamus extends from sensory processing to higher-level conscious perception, and we realise we have assumed a false dichotomy all along?

While it is tempting to treat this study as a confirmation of the thalamus’ role in consciousness, as with many of these ‘psychophysical’ experiments, one must acknowledge subjectivity in scientific interpretation. In fact, there is a whole field dedicated to the science of interpretation: hermeneutics! At Cambridge, neurobiology is taught with a heavy emphasis on critical evaluation, being mindful of reductionist approaches, which come with its pros and cons, and of course, being alert to our cognitive biases. Are we covertly searching for evidence that aligns with our initial expectations? Has our interpretation been tempered by resistance against challenging dogmatic concepts?

This study, too, has been criticised, with some suggesting the detection of increased neural activity may not be linked to conscious perception; rather, it may reflect attention to a visual stimulus, a cognitive phenomenon subtly different from conscious perception. Above all, the difficulty of elucidating conscious perception arguably lies not within the constraints of scientific techniques or subjective interpretations. Rather, it lies within the impossible task of defining consciousness unanimously, the task of demarcating what is consciousness and what is not. The scientific is the philosophical – this is a fact of science one cannot evade from.

Nonetheless, this remarkable study will hopefully inspire more of its kind to come. After all, science quintessentially proves humans are not one to get bogged down by big questions. With all things considered, my big question remains: is that low hum in the background still there? Are you consciously perceiving it?

Comment / College rivalry should not become college snobbery30 January 2026

Comment / College rivalry should not become college snobbery30 January 2026 News / Downing Bar dodges college takeover31 January 2026

News / Downing Bar dodges college takeover31 January 2026 News / Cambridge for Palestine hosts sit-in at Sidgwick demanding divestment31 January 2026

News / Cambridge for Palestine hosts sit-in at Sidgwick demanding divestment31 January 2026 Science / Meet the Cambridge physicist who advocates for the humanities30 January 2026

Science / Meet the Cambridge physicist who advocates for the humanities30 January 2026 Features / Are you more yourself at Cambridge or away from it? 27 January 2026

Features / Are you more yourself at Cambridge or away from it? 27 January 2026