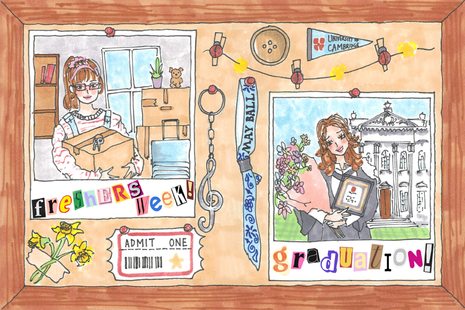

From fresher to finalist: how have you evolved at Cambridge?

Beth Lee asks how students’ world outlook and future aspirations have changed at Cambridge

Anywhere else, three years is a small gap; at Cambridge it’s a chasm. Finalists have attained the height of seniority while freshers feel like small fry. Growth comes in spurts, and university is a uniquely transformative stage of life. Charting the changes in four key domains – relationships, work, world outlook, and future aspirations – shows that a lot can happen in three years.

Relationships

Alex is a third year Law student. Starting out, he remembers “trying to do everything … say yes to everything”. The scattergun enthusiasm of freshers is liable to exhaust. He describes “having a wider group of friends and getting burned out after Michaelmas of the first year. I was left in Lent Term having to be more proactive about what I was joining”. His social circle has contracted, with “fewer friends but deeper connections”.

Fourth year Naomi* describes her fresher self as “shy, but wanting to make friends and being friendly. Probably a little bit more immature and less realistic”. She has become “a lot friendlier and more confident”. Lara is an English graduate, now working as an intern in a local church. Like Alex, she attended several societies in her time at Cambridge, including the African Caribbean Society, several video game societies and the World Film Society. She grew in appreciation for “the connections I made there rather than seeing people as a means to an end of feeling seen or valued”.

“See the limits of the teachers themselves”

The catalyst for change was Lara’s conversion to Christianity: “Conversations became really interesting … after becoming a Christian because I was really interested in the individuals I was talking to.” She also found community in church, which she describes as “honest and open, loving, sometimes sacrificial”. “Other people matter a lot more now than they did,” says Lara. Before university, the things she cared about were “me-centred,” but she has learned to look outward. The fear was that the image she had built up of her academic ability “could all come crashing down”. She realised: “Living that nervously kind of blinded me to the fact that this could actually be a really great university experience.” Becoming less image-conscious enriched her academic experience, too: “Thinking less about myself, I can enjoy the fact that we’re having these discussions … Just being able to move through a thought together is really exciting”.

Work

It is a stated aim of the University to foster curiosity and intellectual autonomy, and “promote the transformative potential of education for societal benefit”. Yet has academic flourishing really occurred over the years?

Alex arrived at Cambridge “definitely very curious and excited to learn”. His intellectual curiosity has stayed alive but sharpened in focus: “Instead of trying to consume as much information as I can … I’m more like I have this question about this thing and I want to read deeply about it”.

Part of the probing spirit is learning from failure: this is a honed skill. Alex says that “the ability to fail so many times” changed his attitude to failure; rather than “wanting to project a certain sense of competence,” he has learned to admit where he is wrong and ask questions to improve. Feeling disappointed about essay feedback “was definitely a formative experience for me,” and he benefited from “being able to fail within supervisions”. He performed best when he came to a subject fresh, without trying to act like he knew it. For Naomi, feedback has become less important as she has come to “see the limits of the teachers themselves,” and not “idolise their opinions as much”.

“His intellectual curiosity has stayed alive but sharpened in focus”

For some people, learning curves after Cambridge; Lara has become more responsive to feedback in her graduate role as a ministry intern. In her time at Cambridge, she recalls that “the same issues kept coming up in my writing”. Although points of improvements were “in the back of my mind,” she says: “I maybe never gave myself enough time to really implement them into my work.” Now that she is working with people: “There’s more of a sense that what I say and what I do and how I could grow … directly impacts the people who I’m working with”. This contrasts with intellectual pursuit for the sake of it: “I suppose while writing essays, the reader feels like someone who’s quite distant”.

World outlook

Cambridge is more than the supervision system: unique influences of politics and culture conflate to shape the social conscience of its students. All three individuals describe a widening worldview.

Coming from the United States, Alex’s world outlook “might have been more US-centric,” and his schools were “very homogenous in the type of people I would talk to”. Now his perspective is “more ambiguous … I don’t know if that’s a good thing or a bad thing”. The breakneck evolution of AI and a flurry of world conflicts have put things into a new perspective: “The world has changed too, and my worldview has adapted to that.”

Naomi felt “very, very wary” starting out in Cambridge because she “didn’t want to disrespect anyone,” coming from a town which “wasn’t very diverse”. Happily, she has learned: “people are happy when you learn about their cultures. They’re happy when you interact with them and take an interest in them.” University itself is a hedged-in environment; Naomi’s year abroad taught her that “life in general will be much bigger than it is at university”.

Lara’s pre-Cambridge outlook was similarly “quite insular … my world was kind of what was immediately in front of me.” She has since become “a little bit more interested in the world and what’s going on in the news”. One influence on her increasing political consciousness was reading a lot of environmental criticism in her third year, crystallising a “vague interest” in environmental politics.

Future aspirations

The evolution of a Cambridge student is not a finished story. Finalists are small fry in the job pool, and face new challenges of career and identity. But in the three or four years of student life, aspirations evolve and concretise.

“I don’t know if I really had a specific design for my future,” says Lara. She “used to feel quite frustrated,” and “lost” about the career prospects of her degree, afraid of “mooching off my parents my whole life”. But she has realised that job titles are often transitory: “Looking at the way a lot of people’s lives are … you probably don’t stay in one role for very long.” She still doesn’t have a formed plan for the future, but “it kind of feels like there’s an adventure ahead of me”.

Alex has become “a lot more confident” about the future, without ironing out all uncertainties. Consistent with his increasing appreciation for community, his plans include “prioritising my family but also being able to create good change in the world”.

Rubbing edges with those of unlike-minded others has a softening effect on many students. Opinions become less entrenched, and people take greater priority. From first to final year, the Cambridge student has a lot to learn. Tracking the changes with hindsight shows that progress is rarely linear. The lesson for freshers? Try, try again.

*Name changed by request.

News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026

News / Union debates officer resigns after misconduct investigation9 March 2026 News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026

News / Man found guilty of murdering Cambridge language school student10 March 2026 Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026

Features / The hidden harms of college stereotypes 10 March 2026 News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026

News / King’s Affair adds charge for half-off workers 11 March 2026 News / King’s faces backlash over formal ticket policy 7 March 2026

News / King’s faces backlash over formal ticket policy 7 March 2026