Stop romanticising Britain’s past

As decolonisation-related activism within Cambridge becomes more prominent, Daniella Adeluwoye explores what this means for the national curriculum and the liberation of our own minds.

When I was young, I would always look forward to the crunch of autumn leaves as they transitioned to a rich orange, because October meant Black History Month. Thirty-one sacred days to finally deviate from the myopic and Eurocentric lens that is our curriculum and indulge myself within the rich tapestry of black history.

But year after year, Black History Month was spent celebrating Britain’s role in ending the slave trade. Did we ever critically engage in Britain’s role in the slave trade in the first place? No. Did we ever learn that the effects of the slave trade transcend its abolition? No. Our national curriculum fails to teach us about the deprivation characterising the lives of former slaves as they were left illiterate and unskilled and how that has created an intentionally orchestrated drawback that remains intergenerational.

"Even during Black History Month, it is white people who celebrate the story of white Britain to the rest of us."

Who tells what version of Britain’s story? My younger self would have been delighted to have learnt about black abolitionists such as Olaudah Equiano rather than hearing about our convenient national hero, Wilberforce. History is not an objective narrative, it is always told by the winners: declining sugar prices and over-competition contributed to the anti-slavery policies that enabled Wilberforce’s glorification; the myth that Wilberforce represents the moral righteousness of Britain fails to consider how the abolition movement, in many ways, just followed existing market trends of the time.

Rather than continually deify Wilberforce, I would have been awe-struck to hear that Britain also had a black power movement, that we too had our events to mirror the Montgomery Bus boycott, such as the Bristol Bus boycott. It is frustrating in retrospect to uncover that we have our own history on our door steps, yet our national curriculum sweeps it under the carpet, because even during Black History Month, it is white people who celebrate the story of white Britain to the rest of us.

"Teach me how the Industrial Revolution was built on slavery and maintained systems of capitalistic domination throughout the world that feeds into neo-colonial economic relationships today"

Growing up as a mixed-race person, I would often pester my teachers with my observations about how Eurocentric the national curriculum was- the British monarchy, the Great Fire of London, the abolitionist movement in Britain. Our curriculum offers us a palatable version of Britain’s history, concealing the blood stains and the cracks of its colonial past such as the devastating effects the Empire had on India. This version of British history has evidently been a romanticising of the nation’s past, we have been led to believe that racism was never our problem and all we did was innocently sip cups of tea.

I’m sorry to disappoint, but Britain’s tradition of tea was built on exploitative imperialism. Britain illegally drugged up the entire nation of China, dragging it through two Opium Wars, forcing the cession of Hong Kong as colonial territory, to maintain this country’s culturally appropriative afternoon drinking habits. So, stop telling me about how Isambard Kingdom Brunel was one of the greatest figures of the Industrial Revolution; instead, teach me how the Industrial Revolution was built on slavery and maintained systems of capitalistic domination throughout the world that feeds into neo-colonial economic relationships today.

"Did we ever critically engage in Britain’s role in the slave trade in the first place? No. Did we ever learn that the effects of the slave trade transcend its abolition? No."

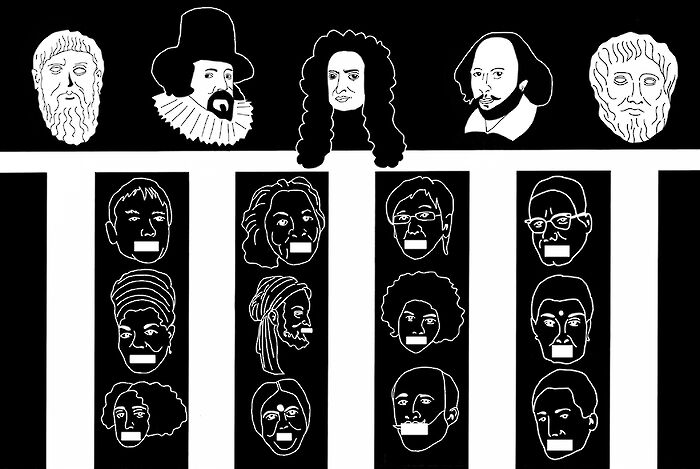

Britain has repeatedly failed to come to terms with its colonial past, but the rise of decolonisation-related activism of Cambridge students gives me hope that we can have those critical discussions about who gets to tell what version of Britain’s story. Yes, the curriculum must go beyond middle-class white men and yes, adding a few BME writers will not harm your sacred western philosophers; but at the same time, this does not necessarily require the removal of all white people from the existing syllabus. It means contextualising white people thought in their colonial context or offering postcolonial readings on existing texts. Take The Tempest for example, we can engage in a post-colonial analysis of the play and allow ourselves to challenge more traditional interpretations.

To liberate our curriculum is to ask ourselves who holds hegemony over narratives and recognising that these supposedly authorial voices are not formed in vacuums- they are reflections of our geo-political institutions and ones that we must not passively consume.

The real danger is that the meaningful issues at stake that concern us all become obscured in our attempts to diversify our national curriculum. It is not just about cosmetic change, we need fundamental change to our education system because when Caribbean girls and black schoolboys are disproportionately at the bottom of the education system, making Chinua Achebe a compulsory author to study is not going to be their saving grace. We must also address issues of unconscious bias and low expectations amongst teachers and what effects this has on their students, but a more liberated curriculum would undoubtedly be a starting point in helping students feel included within the education system and ensuring that there is a meaningful and personal connection with what they study. Because as inquisitive young students who want to explore their own identities during a crucial period of their lives, Henry VII may not be the best historical figure in allowing us to do so and there is only so much we can explore within those fleeting 31 days of the year.

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026 News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026 News / University Council rescinds University Centre membership20 February 2026

News / University Council rescinds University Centre membership20 February 2026 News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026

News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026 News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026

News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026